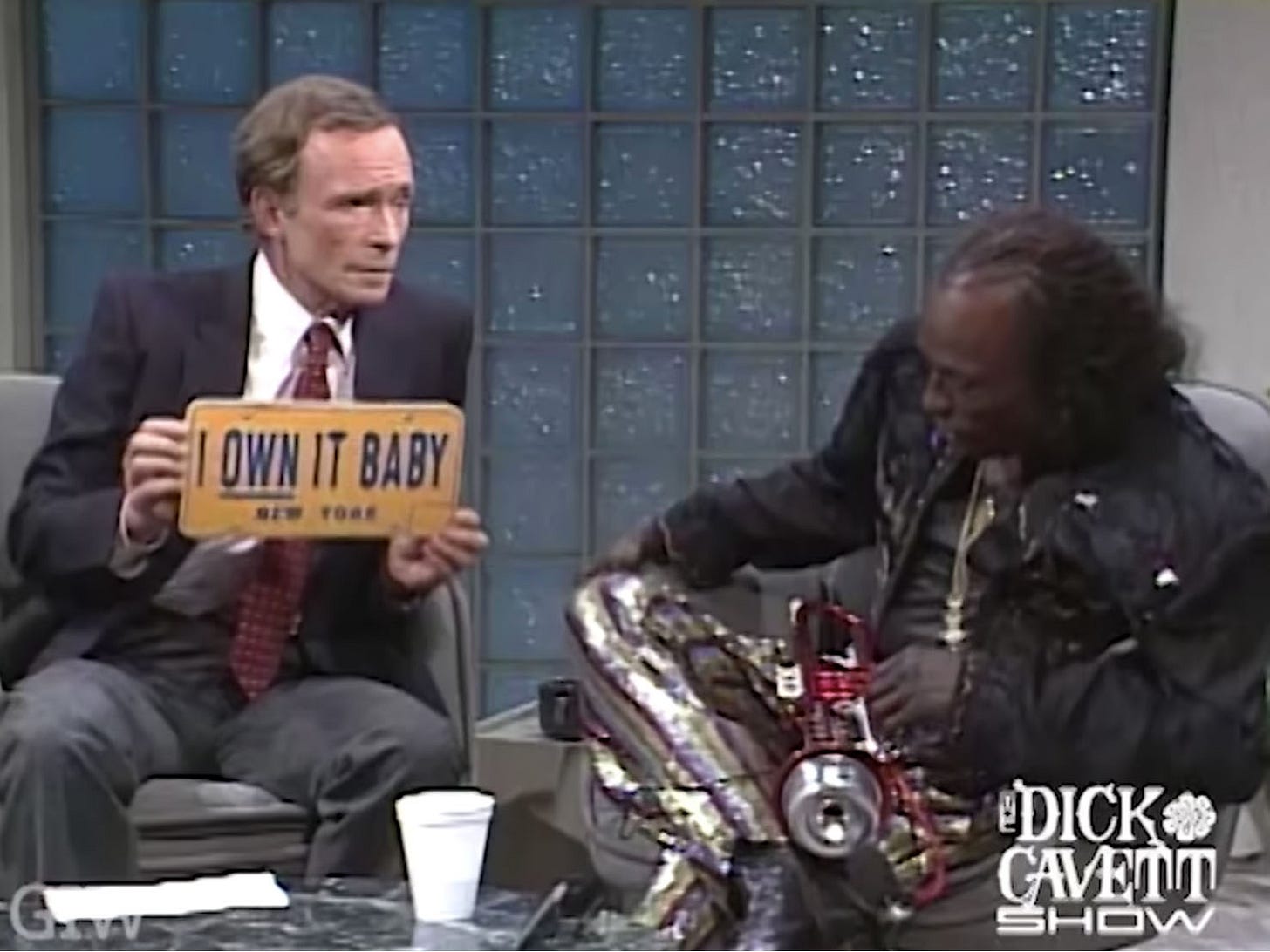

There are two sides to the Dick Cavett coin, but we’re capable of nuance here at DAVID, aren’t we? It suits our subject, too. “You invert things so beautifully,” actor Richard Burton, the star of Part 2 of this series, tells Cavett in 1980. Five years later, while interviewing director Paul Schrader about his bio-drama, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, he makes the mistake of saying that writer Yukio Mishima killed himself at the age of 54. “45,” Schrader corrects him. “I always reverse numbers when it’s the other side of the world,” Cavett charms back.

As much as I’ve appreciated The Dick Cavett Show’s YouTube renaissance, it’s generated a lot of Cavett lionizing without enough Cavett critique. In an early-pandemic piece for the BBC, Christina Newland claimed that Cavett was the “greatest talk show host of all.”

Cavett’s style of hosting and of initiating genuine conversation with his guests – neither pandering to them nor acting smugly superior – reflected how entertainment and cultural spheres were liberated by the bohemian spirit of the 70s.

Now, I like this piece. It’s an informative bit of writing that captures the nostalgia that streaming Cavett can evoke for people born after his heyday, especially when compared with the dismal quality of late-night television in the 21st century. As Cavett himself said a few years back, “There’s no honor, now, to have a talk show.”

But while I agree with Newland that Cavett is one of the greats, if not the greatest, she’s dead wrong about his treatment of his guests. Though genuine, funny, and at times even sweet, Cavett can be not just smug and superior, but cruel. In fact, there are guests with whom he is nakedly dehumanizing, particularly when those guests are white women, and especially when those guests are black men; unsurprisingly, precious few black women were ever on The Dick Cavett Show as guests during its prime, and off the top of my head, I can only think of two—Shirley Chisholm and Alice Walker—out of the dozens of episodes that I’ve seen. To overlook this tendency toward bigotry (to dust off a word that Cavett himself would have used back in the 70s) is not just to do a disservice to those guests, but to misunderstand Cavett as an interviewer.

Though Cavett’s challenge as the Interlocutor—at which he often succeeds, and which others so often fail—is to draw history, insight, truth from his guests, his own shortcomings, as we may euphemistically refer to his supremacy logics, regularly overwhelm him. What makes these failures so striking, at least to me, as a white person of redacted gender, is that I get the sense that he does it defensively; in moments of powerlessness, insecurity, or mere dead air, Cavett will jockey for the top by belittling his guests, and when this happens, the guest in question is rarely a white guy.

This tactic for self-aggrandizement is far from unheard of among men and white people, whether or not they/we are hosting a talk show. But when I use the word failure, I mean it in the sense of Cavett’s project as interviewer, rather than in the sense of him being a nice person. In these moments, Cavett changes the focus of the interview; that is, he fails at his task of revealing his subject, and instead reveals himself.

These failures are all the more striking when you consider Cavett’s reputation for control. Taut as piano wire, Cavett’s penchant for preparation is so severe that it actually works against him; he would go on to joke that in the early days of his show, he trained himself to have stock questions at the ready for when he missed what a guest said because he was “too wedded to his notes.”

This reputation for control is why Cavett’s loss of it when with a guest who isn’t a white man is so fascinating, to me, anyway. This isn’t to say he doesn’t sometimes go in on white male guests1, but he tends to be forgiving of even the trickiest weirdos, from the Thin White Duke to Brando at his most lampooned. At worst, the energy Cavett brings to these guests isn’t unlike that of a kid brother: irritating but harmless. As Esquire writes, while he doesn’t throw softballs, he’s “no firebrand griller,” either.

A possible emotional inverse of impish, an adjective often used to describe Cavett, is, I think, waspy, which is how he can be with the women he interviews, especially if they are regarded as sex symbols. “Here they are, Jayne Mansfield!” is the joke that famously got Cavett his breakthrough writing gig on Jack Paar’s Tonight Show, and I’ve often thought that its offense is located in the assumption that Cavett has the altitude needed to condescend so hard. For every interview where he mansplains to Gina Lollobrigida or speaks over Yoko Ono’s head is another where his attempts at belittlement fall flat because, well, he’s a little bitch. Most of the women he interviews, white or not, have been socialized to disappear male aggression with grace and camouflaged wit, but a lot of them let it rip with Cavett, who’s so easy to humiliate it’s almost not fun. Whether he’s being ganged up on by Janis Joplin and Gloria Swanson (a setup that feels like an acid trip in and of itself), or Lucille Ball and Carol Burnett, one has to wonder if Cavett actually likes it. He certainly asks for it.

It is easy to recognize the sexism in Cavett’s treatment of (mostly) white women because, broadly speaking, we still only recognize sexism as a white woman’s problem2. I would suggest that Cavett’s treatment of the black men who are guests on his show is also sexualized, perhaps even to a higher degree than that of his white women guests.

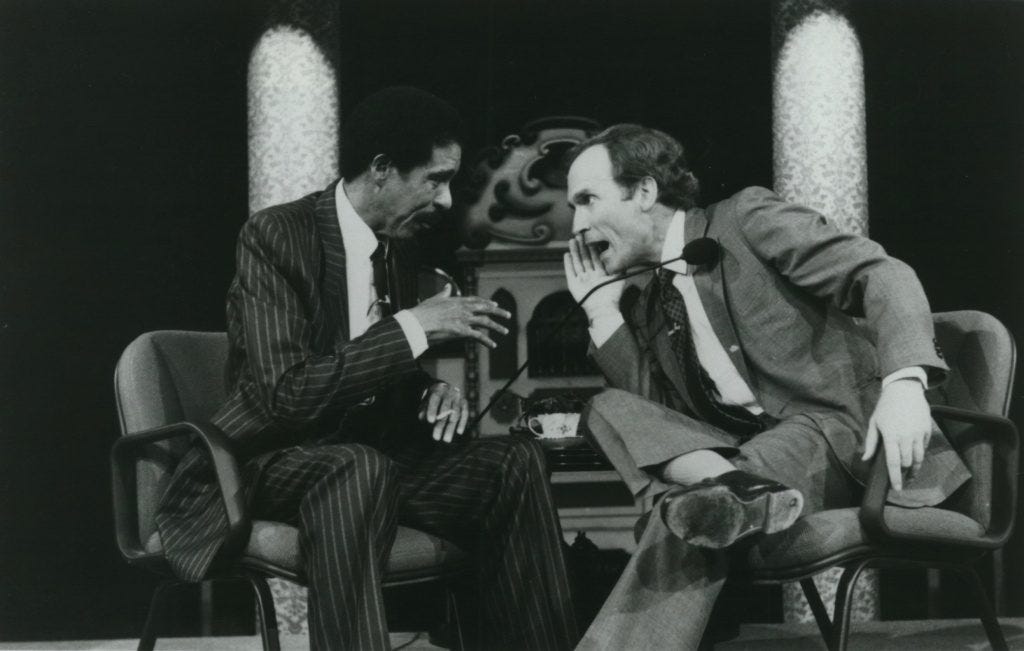

Take his 1985 interview with Eddie Murphy. It begins with Murphy teasing the house musicians, a group of white guys who’ve never been to New Orleans, for calling themselves the New Orleans Jazz Band. I’ve said that Cavett is charming, but Murphy, as we all know, could out-charm him any day of the week. Still in the midst of his atmospheric rise to fame, Murphy’s charisma is soft yet sparkling. As Cavett triangulates the young comic’s burgeoning career with that of the even-then legendary Richard Pryor, he quickly draws Murphy into a conversation about his earliest memories. When he brings up Mark Twain out of nowhere, you barely have enough time to recognize that you’re on edge before he asks Murphy, his voice rippling in gleeful caricature, “Are you offended by the word ‘n- - - - -?’”

Murphy’s demeanor transforms. “Why…Where is this coming from?” he asks. He is bewildered. He hardens.

“Did I say that?” cries Cavett, campily clutching invisible pearls.

The interview continues. Though he recommences his teasing, Murphy is never once rude, but neither, I think, is he ever warm again. I was shocked to hear the word come from Cavett’s mouth, though perhaps I should not have been. While surely informed by my inexperience with racism, however, my shock was also due to having watched, just before, one of Cavett’s sycophantic interviews with Pryor, the comic genius that he plainly idolizes—and whose work inspired Murphy, too.

The sexualization takes more shape when you zoom out from this one interview. While talking with Marc Maron decades later, Murphy says that he got to know Cavett well outside of The Dick Cavett Show. Cavett “popped up” a lot, Murphy reports. “I used to hang out with Dick Cavett a lot. If you dared him to do anything he would do it.” Once, while watching Diana Ross perform at Madison Square Garden together, he dared Cavett to grab Ross’s ass. “Why you doing this to me?” Cavett plaintively demanded. But then he fucking did it—went right up onstage and did it, to Murphy’s bemused entertainment. While I won’t excuse Murphy’s role in this scenario, Cavett’s willingness to entertain it screams humiliation bottom. How can such a grudging fixation on someone, described in some circles as a fetish, not be sexual, I wonder? To speak of triangulation again (and to evoke, on some level, Barbara Kruger): how can you, as a man, sexually assault a woman at another man’s invitation and not feel an erotic charge with him?

From all that I’ve seen and read, Cavett appears to simultaneously worship and revile black men, compulsively seeking their attention by provoking outrage and offering bizarre displays of submission, usually in encounters that make him appear more like a member of the entourage than a friend. There’s another story, this one told by Cavett himself, about going on vacation with none other than Muhammad Ali. When Cavett cooked breakfast for the both of them, he turned around to find that Ali had eaten all of it.

When he realized what he’d done he put on a hilarious, pitiful sad look and murmured, “Oh, Dick. You never gonna invite me back.”

It was so sweet, I almost cried.

Like all bigots, passive and active, Cavett has this tendency to position himself as a pseudo-victim, even in this attempt at humor, which lands for me as both condescending and pathetic. It’s akin to the extremely cringe largesse that Norman Mailer demonstrates when the writer and Ali are on The Dick Cavett Show together in 1970. “I came here to pay my respects to you tonight, that’s why I came on after you,” Mailer tells Ali, offering his honor like an adult giving a child a ballon, grinning with all of Spongebob’s teeth and none of his humanity3. Mailer waits, as if expecting Ali—who almost went to prison and missed out on four of his prime athletic years for refusing to be drafted into America’s imperialist war against the people of Vietnam—to be grateful for his praise. Ali’s response is steeped in a quiet dignity that imperils the remainder of the interview with its restraint. It punctures Mailer’s balloons. It makes shit awkward.

Over the past few years, I’ve begun to think of the interview as an art form, one serious enough to merit rigorous critique. Cavett, like almost everyone, is a person of his time, and we are hardly surprised that he demonstrates racism, sexism, and the like over the span of his 50-year career. These are, in my opinion, personal ethical failings with personal and social ramifications for the people they effect.

They are also artistic failings: to succeed creatively as an interviewer, one must interview a subject, and the subject can’t be a subject when they’ve been objectified. But even in his obscuring of his subjects, Cavett, as I’ve said, reveals himself. To paraphrase painter Francis Bacon, when you paint something, you’re painting yourself, too.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial. Preorder their second novel, X (Catapult, 2022).

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, an advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

There are exceptions, as with the famously homosexual and at that point socially dethroned writer Truman Capote. “I haven’t seen very many people for the last three years,” Capote tells Cavett in 1980. “A lot of people would say it’s because you have no friends left,” Cavett lobs back.

Exacerbated by straightness, cisness, money, thinness, non-disableness, etc.

Like any normal person, I loathe Norman Mailer, who physically sickens me.