Forgive me if you’ve read this spiel before, but 2020 was hard. I spent half of COVID-19’s inaugural year at my mom’s house in Northern California, helping her care for my older sister. On top of multi-day shifts with C (whose needs can often be intense), I was working full-time and freelancing, too, petrified of getting laid off again, as I had in the first months of the pandemic. My gay family was hundreds and thousands of miles away, and I was by myself in a town where I don’t know a soul, other than estranged relatives and two of my three sisters, who due to age and other factors are more like my children than my peers. There have been times in my life where I have felt more isolated and exhausted, but there haven’t been many, and 2020 was the first that the possibility of my sweet C, alone in a hospital that might consider her IQ reason enough to let her drown on dry land, ornamented my nightmares.

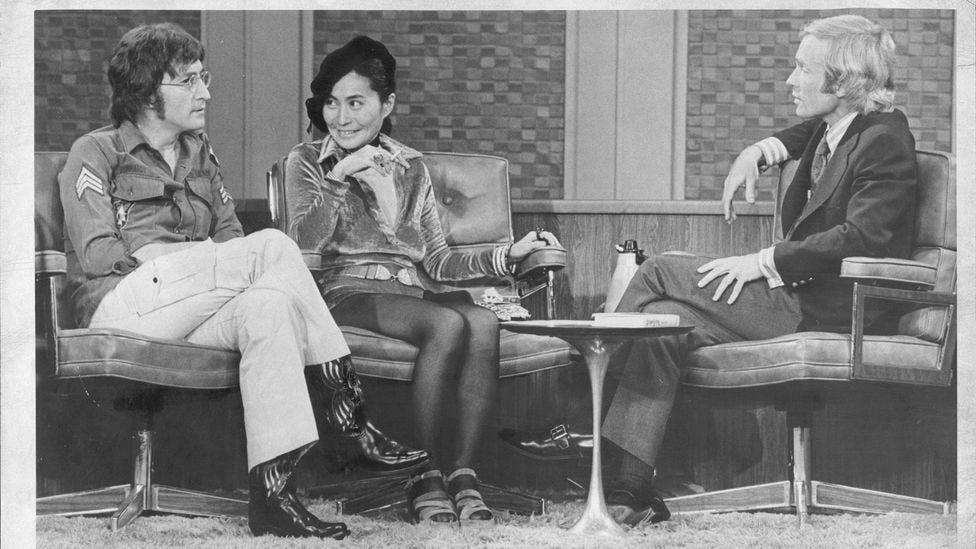

I don’t remember why I started watching episodes of The Dick Cavett Show on YouTube, but suddenly it was a part of my solitary nighttime ritual, the hour or two before sleep when I laid down on my mom’s yoga mat, chain-smoked joints, and anticipated another 16-hour-day of muting C’s screams over Zoom meetings while trapped indoors by viral plague and fire season. Delighted by the seemingly endless roster of famous subjects—including Salvador Dalí, Katharine Hepburn, Judy Garland, Miles Davis, Muhammad Ali, Marlon Brando, Orson Welles, Lucille Ball, Truman Capote, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Richard Pryor, and my beloved Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni—I found myself entranced by the pedantic patter of this boyish Midwesterner, who over the course of almost 40 years of hosting his self-titled talk show has aged from Pinnochio-esque whippersnapper to batty examiner emeritus.

I started joking (mostly to myself, because I was mostly alone) that my new favorite movie was Cavett’s 1980 interview with Welsh actor Richard Burton, the Shakespearean heartthrob considered the successor of Laurence Olivier, and of a generation with Richard Harris, Peter O’Toole, and Oliver Reed (though in the interview he talks at length about his close friendship with American actor Humphrey Bogart, born a quarter-century before him). I was already familiar with Burton, but not overly, my association being mostly his leading role in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1966) and his supporting role as wife-guy to Elizabeth Taylor1, to whom he was married (and divorced) two times.

But despite Cavett’s reverential preamble to the episode, the actor, whom he describes as “graceful without effeminacy,” needs no introduction. Leonine yet poised, unleashing his languorous baritone with the razored elocution we recognize from his stage work, Burton’s fading physical beauty describes an unassuming yet arresting comfort in the spotlight. If you haven’t seen this interview, go watch it—right now. I could watch it over and over, and have, letting it play in my apartment as I do dishes or clean, sometimes catching myself raptly listening, while leaning on a broom like Cinderella, to what Vanity Fair called Burton’s “Welsh-barroom raconteurship.” You can’t believe that it’s extemporaneous, the way he spins outlandish yet tender stories about his coal miner father, expounds on the craft of acting, muses on attachment trauma and alcoholism, and coyly divulges old Hollywood lore; and yet were you told it was a performance, you would also find it unbelievable.

Shoeless, in a blue suit and brown tie, Burton appears older than 54, and indeed, he is only four years from his death of complications from alcoholism. Aged both by drink and his resemblance to a Roman statesman2, he speaks beautifully of his home—“I don’t know if it’s the coal dust in the air or the eternal rain, but certainly most Welsh people sing mellifluously,”—casually recites from Hamlet in both English and German, and charmingly disparages his looks, his acting, and his writing, calling his diary “unreadable,” though at the time you could find excerpts of it in magazines like Ladies’ Home Journal3. He doesn’t watch television and doesn’t like being touched by other actors, particularly when shooting love scenes. He tells Cavett that he calls everyone he respects by their full first name, and then, after an avuncular feint to the contrary, proceeds to call Cavett by his, igniting, briefly, a kind of male homosocial warmth that’s hard to describe without irony. Dudes rock.

But that’s all I’ll say about that. If I don’t leave Burton alone now, I never will. This post is not about him, but the man sitting to his right, in earth tones to suit the drab tail-end of 70s talk show decor. Petite and fine-featured, he’s a sparrow to Burton’s eagle4. In 1980, Cavett is 12 years deep into his solo show, in control, even if obviously impressed by his guest. Almost ingratiating, but not quite, he guides Burton through his earliest childhood and into the most sensitive of subjects of his life—booze, women, and the insecurities strong enough to plague a man who got halfway to an EGOT—navigating commercial breaks as gracefully as Burton the stage. “You are clever,” Burton tells him, and as abashed as Cavett plainly is, the little bird is unflappable. “You’ll notice that more and more as we go,” he says, and his audience laughs.

Then in his mid-forties, Cavett had had the kind of early success that, even skewed for his being a white guy and all, seems ridiculous in the age of the internet. After reading that Jack Paar, then the host of The Tonight Show, needed material for his opening monologue, Cavett wrote some jokes, put them in an envelope, and went to the RCA Building, where he hand-delivered them to Paar himself. Parlaying his luck (doesn’t that story feel massaged, like Lana Turner’s soda fountain?) into a writing gig on The Tonight Show and a brief career in stand-up, in 1968 he began hosting for ABC, and continued doing so, on one network or another, until 2007.

The Dick Cavett Show’s glory days, writes Esquire, “were undoubtedly in the early Seventies…The immensely more popular Tonight Show with Johnny Carson traded in big laughs, and his legacy can be felt in the fact that every current late-night host is either a former comedian or writer. But Dick Cavett, despite his stand-up background, was a conversationalist first and foremost. His was a subtle, impish wit. He was simultaneously disarming and confrontational. It made for some of the greatest televised interviews ever broadcast.” But Cavett is not remembered like his contemporary, Carson, or Carson’s successors, from David Letterman all the way through to James Corden (although when Stephen Colbert had Cavett on last year, he told him that he was his idol). For a guy who had enough of a presence to be threatened by President Nixon himself, he seems, if not forgotten, then often overlooked, at least here in his own country.

I think this is because Cavett wasn’t like those other guys. “Cavett facilitates,” writes Christina Newland, fellow Cavett stan, “wry and unassuming, chairing gatherings that have the intellectual air of an old-school Parisian salon.” Though he talked often about being a comic, he was not an entertainer, like Carson. Though sometimes provocative or combative, he was not a provocateur, like Howard Stern, nor a pugilist, like Letterman. He was not an edutainment hack, like Jon Stewart or Colbert, nor a babysitter, like Jimmy Kimmel, nor a plant, like Seth Meyers, nor a dead-eyed consent manufacturer, like Jimmy Fallon.

No. As Esquire writes, he was a conversationalist, and while he wasn’t always as successful with his guests as he was with Burton, he cultivated something that it’s easy to feel nostalgic about, even if you weren’t alive to see it. Like many of us, I’ve spent the pandemic yearning for Before. As Newland writes, “Watching his show now, cooped up, makes me yearn for the days of public intellectualism, when the contrasts between people were celebrated for producing the most striking and engaging discussions, rather than manipulated and exploited for entertainment.” I think I disagree with the mythologizing inherent in her claim, but I feel, very deeply, the emotion from which it stems.

But more on that next time.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial. Preorder their second novel, X (Catapult, 2022).

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, an advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

The star of her own interviews and to whom we will return over the course of this series.

Often cast as a Roman onstage, Burton reminds Cavett’s audience that his native Welsh is deeply influenced by Latin, the language of Britain’s old conquerors.

Or maybe it’s better to be specific with the red kite, the national bird of Wales.