Not too long ago, I hooked up with a weird old man who made his own electronic music and had been to prison for stabbing his ex-girlfriend’s drug dealer. That’s a lot of information to get out of a single encounter with a stranger, but this guy—let’s call him Derek—loved to talk. Blowhards tend to be unobservant, but Derek paid close attention to whether I was listening and how, modulating his narrative according to my interest (more about his time milking morphine on the burn ward after the gas explosion; less about his childhood in fifties Williamsburg).

Derek was also sensitive to the fact that I’m, let’s say, susceptible to negging in the right context. I suppose it’s not strictly negging that I mean here, but rather that strain of flirting that manifests as verbal jockeying, a power struggle that’s less a true conflict than the slow, interactive reveal of one’s personal predilections. It’s fun if you’re into antagonistic sex, which I am. Derek immediately grasped that he could neg me in order to recapture my flagging attention—something I wasn’t about to put any effort into concealing—and to great effect, I might add.

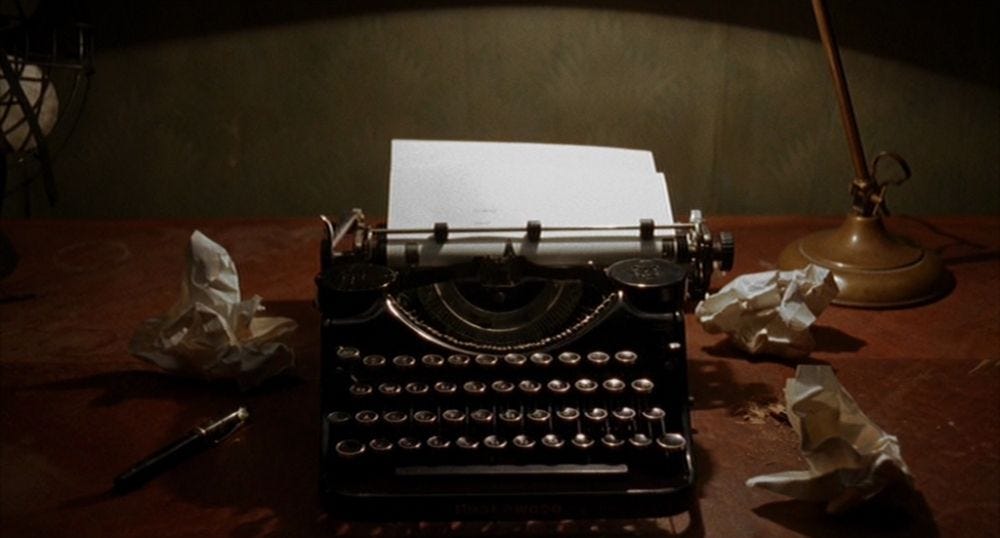

When I told him that I’m a writer, he began yarning about a closeted writer friend of his (one you might recognize if I shared his name) who had been unrequitedly in love with heterosexual Derek back in the nineties. Though this new story was engaging enough at first, it wasn’t long before he started getting bogged down in the details. Naked on his bed, boredom soon got the better of me. I played with my hair; I chewed a hangnail. Watching my eyes wander his wall-to-wall bookshelves, linger over the switchboard-looking thing where he made his music, leap to his phone every time Grindr clucked, Derek patiently waited for my focus to make its perfunctory return to his face before he did it again.

“I wasn’t surprised that he ending up blowing his head off.” He watched me as he reached to stroke my leg. “Writers are obsessed with love because they don’t get enough.”

If you’re after attention, and who isn’t, you’ll know that the most attentive observers will perceive your faults as well as your charms. As I’ve said before, the appeal of the sadistic type is quite simple: They're genuinely interested in you, which is very rare indeed.

Derek’s assessment of why we write—or rather, why we become writers—rings true for me, at least somewhat. Though the idea of getting onstage terrifies me, I have always felt an affinity with performers, comedians, and actors, artists who lose themselves in exposure, preferring power over privacy and validation over safety. As writers, we have landed on this most literal of ways to control the narrative, telling all, some of us more slantly than others, so that nothing can be revealed against our will.

I will be generous to us and say that insecurity isn’t all there is to it—powered only by neuroses, our craft could not also be art. Soothing as it feels, control is the opposite of communication. When we fail to take it in hand, something more interesting happens. This is a good thing. But more on that next time.

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.