David Hollander

On "American Gigolo"

If you’ve never seen American Gigolo (1980), you should know going into it that the soundtrack is basically Blondie’s Call Me on a loop. I’m not joking, and neither is Paul Schrader’s neo-noir crime drama, which doesn’t have the sense of humor for even a joke as bad as “soundtrack for movie about classy male escort is literally just Debbie Harry, synths, and vibes.”

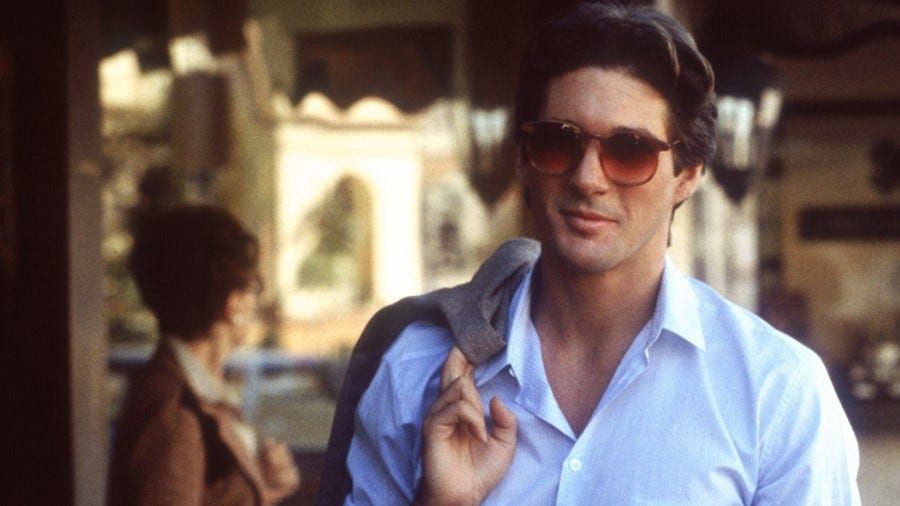

For such a humorless movie, you need a humorless leading man, and there’s no better guy for the job than Richard Gere, who stars as Gigolo’s Julian Kaye, the venal, avoidant, polyglottal hooker* with a heart of cold. If you know his work, you know that Richard Gere is a bad actor. I’ve never once seen him in a role that made me think, “Wow, Richard Gere just gets it!” He is bad, and the more he tries, the worse he gets. If there’s a joke, in Gigolo or elsewhere, he isn’t in on it.

But I contend that this lack of humor is one of Gere’s great strengths as an actor, along with his natural presence. In the vein of campy silver screen sirens who are more style than substance, he’s our beautiful flat-abbed mannikin, our boy of not getting it, our himbo supreme. If you so very charitably thought that this flatness was merely his actorly approach to the role of the American gigolo—a breathtaking young man who has built a sumptuous lifestyle around his talent for hustling—you would be wrong, although you might be forgiven for thinking so. We know how the movie tropes flatten and dehumanize prostitutes of all kinds.

No, Gigolo is not unique: Gere brings this emptiness to all of his roles (is it a Buddhist thing?!). I can’t think of a performer whose preternatural dullness is more contradicted by their charisma. People claim that this is what is so compelling about Kristen Stewart, but I have yet to be interested by anything she’s ever done on camera (she is both hot and capable of putting me to sleep—a dykon!). Breathless (1983), Officer and a Gentleman (1982)—these are more or less braindead, unwatchable movies, but I will watch them, and it’s not just Gere’s smokeshowliness that keeps me in my seat. I insist that it takes more than beauty to carry a beast.

My knowledge of acting as a craft is pretty limited, but I’m aware of the case to be made against overthinking it, one that has not infrequently come from some of the field’s legends. Recall Marlon Brando, who connected his work to the lies we tell every day “to survive,” or that infamous anecdote about Laurence Olivier and Dustin Hoffman on the set of Marathon Man. We talk about the It Factor, how some actors have it and some don’t, about how all the training in the world can’t imbue it and yet how no level of intellectualization can substitute for it—keeping in mind that the craft itself can be improved upon with discipline and study, as we have learned from other legends like Joan Crawford and Marilyn Monroe, avid students both. (I’m fighting to remember which actor said that you can’t teach talent, but that if anyone has ever been able to learn it, it was Kevin Spacey. I can’t).

If we take these arguments at face value, it stands to reason that someone who does not think at all might actually be a very good actor, after a fashion. Enter Gere, whose seriousness is the seriousness of the perpetual straight man, and which lends maximum authenticity to his approach to Julian, who can be compared with a cucumber in more than one way. In the hands of a good director, the shamelessness of the occasional, well-placed violence or histrionic (“I got nowhere else to go!”) can be powerfully effective, and Gere has ridden that all the way to the bank. When it issues from a place even lower than instinct, this is what we mean when we refer to acting natural.

Back to beauty and beastliness: In my opinion, there’s nothing wrong with a gorgeous, empty picture. And despite its promisingly spicy plot—Julian’s life is thrown upside down when he’s falsely accused of murdering the wife of wealthy and powerful client—Gigolo is mostly style: 80s clotheshorsery, bloodlit basement bars with strict dress codes, SPF 0 sunbathing in Malibu beach houses, beige Westwood apartments where only beautiful childless people live. Cocaine and Armani. Skinny blond/es. Foodless dining. Gigolo is just as much L.A. lookbook as movie, and I love her for it.

According to Wikipedia, Schrader considers Gigolo to be one of four similar films, which he calls “double bookends.” The others are Taxi Driver (1976), Light Sleeper (1992), and The Walker (2007). Until writing this DAVID entry, I hadn’t realized that Schrader wrote Taxi Driver, which I watched constantly as a teenager. It’s interesting to reflect on what De Niro does with the stranger that Gere doesn’t (and vice versa) in these “man in a room” stories, as Schrader calls them. De Niro’s Travis Bickle is hot but cold; Gere’s Julian Kaye is warm but cool.

Now, onto gender. Don’t worry, I didn’t forget. The movie about the pretty man in a feminized career can’t not be about Gender.

There’s more to Gigolo than its hard-boiled plot. It’s also about a prostitute who has become too confident and skilled for his pimps and procurers to screw him anymore; the two of them we meet bitch about not getting the cuts they used to when Julian was a younger guy. Without an alibi for the night of the killing, the cops circle, the noose tightens, as Julian, increasingly panicked, loses control over his perfectly manicured world of Hugo Boss ties, Mercedes Benz 450 SLs, wealthy foreign milfs for whom he practices Swedish on tape while hanging suspended from the ceiling of his tony apartment. When the cops come for him, his pimps are either passive, letting the wolves get him, or they’re angling for a new way to capitalize on the now-cornered Julian Kaye. That’s pimps for ya. That’s bosses for ya.

Julian is frequently judged, criticized, and mocked for his job, and for loving his job giving pleasure to older women. “But it’s illegal!” says the uncomprehending dick, played by Hector Elizondo, hired to investigate his case. Julian easily dismisses the laws governing his sexual life. “Stupid,” he deliciously scoffs in a manner that’s almost punk. When the husband of Julian’s lover scornfully says, “I know a whore when I see one!” we remember that this man is a politician who is bought and sold by the highest-bidding corporations; all Julian Kaye sells is his time and attention, and no one gets hurt (or exploited) in the process.

Julian looks keenly past the pigs and pols and pimps who take issue with his hustle, who take issue with it because it’s a good one. We watch Julian refuse to be bargained down, wheedle expensive gifts out of wealthy, horny women, and set and maintain his professional boundaries. Despite being white, straight, male, and loaded, he embodies the whore that America wasn’t ready for 1980 and sure as shit isn’t ready for now: a person with a job that they’re very good at, that pays well, and that they occasionally enjoy.

Part of this is because the whore (a figure inextricable from bad woman, from crazy person, from poor person, from non-white person, from trans person, from faggot, from pervert) is destabilizing in and of itself. The other part is that Julian’s mode is focused on the pleasure of women—itself untenable in the world of Gigolo and any other that I know of. His heterosexual desire is, in fact, queer-coded. It is unmanful to be as invested in women’s happiness as he is! In fact, it’s absolutely gay! Julian is deeply misunderstood by the straight men he encounters, especially the pig, with whom he has a jocular, teasing relationship until he’s under arrest.

Gigolo is about women and it’s also not about women, grounded in the male homosocial reckoning of a man who is a whore for women (just imagine!). When Julian’s lover, Michelle (Lauren Hutton), complains that when he has sex with her Julian “goes to work,” Gere’s frostiness conveys a sad disappointment. Hasn’t he just given her the pleasure she is denied by her husband, a bespoke orgasm by a gorgeous professional fuck? But no, she wants something more from her fantasy, or rather, now that she has brought her fantasy home, she has found it wanting because she has found it to be human, and nothing kills the mood faster than humanity. Julian understands intuitively the power that her objectification gives him, while also being hurt by its unfairness, one that sex working people all over the world are exposed to by partners who don’t see them as people. There is something about Julian’s centering of female pleasure as both sensibility AND dissociative technique that feels very stone butch to me, but maybe I’m projecting.

Speaking of Julian’s queerness. Pussy magnet obsessed with sexually pleasuring (older) women that dissociates during sex? Sounds FTM to me. Gigolo is unique in that it’s a mainstream Hollywood film with full-frontal nudity by the leading man, which doesn’t make my case any weaker. Julian’s cis body is not truer than the energy of a butch faggot who loves women.

Interestingly, Gere, he of the eternal gay rumors, chose the role of Julian because of the Gigolo’s gay (sub)text.

“I read it and I thought, ‘This is a character I don't know very well. I don't own a suit. He speaks languages; I don't speak any languages. There's kind of a gay thing that's flirting through it and I didn't know the gay community at all.’ I wanted to immerse myself in all of that and I had literally two weeks. So I just dove in.”

The role almost went to Travolta. I rest my case.

The last full-length DAVID that was about a David other than me was published in July. As I wrote the David Sutton series—which is about trans representation, Joan Crawford, and the Joan Crawford vehicle Possessed (1947)—I was beginning to put together a pitch for DAVID to become my third book. A few dozen entries in by that point, I realized that I needed to stop publishing new DAVIDs so I could save some for print. Now, DAVID is about more or less whatever I want (interspersed with GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, a very reasonably priced mutual aid project I’m doing with an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth).

But I’m still collecting Davids (feel free to send them my way!), and there are a few in the quiver that, while fun, probably won’t have a place in the DAVID book, if ever it comes to pass. These Davids tend to happen by deduction: I pick a topic I want to write about and then google around until I find a connecting David—however weak that connection may be—to justify it. That’s what I’ve done with this post, because I’ve wanted to write about American Gigolo for a couple years now and it turns out that David Hollander is the name of the producer who is rebooting it for a Showtime series starring Jon Bernthal.

I’m very curious about how the sexual politics of the original Gigolo will be depicted in this series, and whether they’ll translate to 2020 and to a much more butch actor. Which isn’t to say Gere as Julian isn’t butch, but he is butch in a gay way, not a straight way (butch not as referent but as positionality). As Julian, Gere is a man who casually alludes to having fucked other men for his work. He interacts with gay men, from his ex-pimp, Leon (Bill Duke), to random leathermen in a gay club he briefly enters, without a trace of self-consciousness. He is completely comfortable around fags, but nonetheless prefers to fuck women, and insists on it at this point in his professional life.

And yet. There is something about the way he slinks, like the panther that Connery was in his youth, that is suspect. Gere’s pillowy lips and perfect nipples remind of us a time when straight didn’t mean heterosexual, but on-the-level, legal, normal, conventional, safe. Despite Julian’s relative access, his sometimes unbelievable comfort with wealth, power, and politics, and his literal heterosexuality, he is not an entirely straight man.

As I said, I am very curious about how the sexual politics of the original Gigolo will translate to a 2020 series. I am not optimistic.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial.

*If you’ve never had sex for money, I encourage you to use the term “sex worker” or “erotic laborer” when talking about people who engage in transactional sex.

This essay changed my life in some totally unknowable and undefinable way.

YES! I can't wait for your third book! 👍 David, how do you know something is queer coded? Do you just come with it yourself? It have always confused me projecting what I WANT something to be queer vs. recognizing typical queer traits in media. Since, I start thinking about real life. But at the same time shouldn't there be media that is straight up just FICTION and MADE UP. ✌️