David Clemens, Part 1

On being touched

TW sexual assault

While I was at a restaurant last weekend, a friendly waiter unexpectedly put his hand on my back. It didn’t feel good, but I did nothing except blink and tighten. Eventually he went away.

I surprised myself. Two years ago, at a Yoga to the People class in Berkeley, California, the instructor snuck up behind me to slide their palm across the skin above my kidneys. They were trying to adjust my form. It was 7:30 in the morning, the window-walled room crepuscular and dense with the sound of pan flutes.

I shrieked and swung, narrowly missing the instructor’s face with my fist. I don’t remember their gender. They didn’t apologize—I’m sure I scared them—but moved away, back toward the front of the class, and after a moment caught in the startled stares of college children and granola crones, we all continued on with Our Practice as if nothing had happened.

Even though I knew that the instructor meant no harm, I still kind of wish I had made contact, completed the gesture.

I’ve written at some length about my relationship to touch. I should start by saying that I love my stone sexuality, despite the fact that, like leathersex and homosexuality, it’s stigmatized as deviance, and because of heteropatriarchy, is associated with violence, pedophilia, and criminality. It doesn’t always sit easy with me, but stone is what I am for now, and I’m grateful for what it does for me. I know several stone queers—butch, femme, and otherwise—and I’m grateful for them, too. It’s a shared experience that I would have a much harder time understanding, and embracing, without them.

Though I trace some of my own desires back to bad experiences in my life, I want to make it clear that I don’t think one must necessarily relate so-called deviant desire to trauma. Nor do I think that there’s anything wrong with being influenced by one’s experiences, which, for the vast majority of us, are shaped by pain as much by anything else. I want to write about the tricky parts of being a stone leathersexual without failing to honor the long history of trans, queer, and pervert people with which it connects me, and with the magnificent resilience of those with the courage to claim, rather than reject, their own bodies as they are in the moment—not to mention with the stone queers I know in 2020.

Because even though many of us struggle our stoneness—a state that can be sporadic or lifelong—I know that there is also dignity in this identity, which we can follow back many years, long before we were even born (DaemonumX is a great resource for learning more about our erotic heritage as leatherpeople!). Stone sexuality, like other practices of gender-nonconformity, connects us to the queer people who came before us. For me, it’s a connection to the first person I ever understood to be like me, in this way and others.

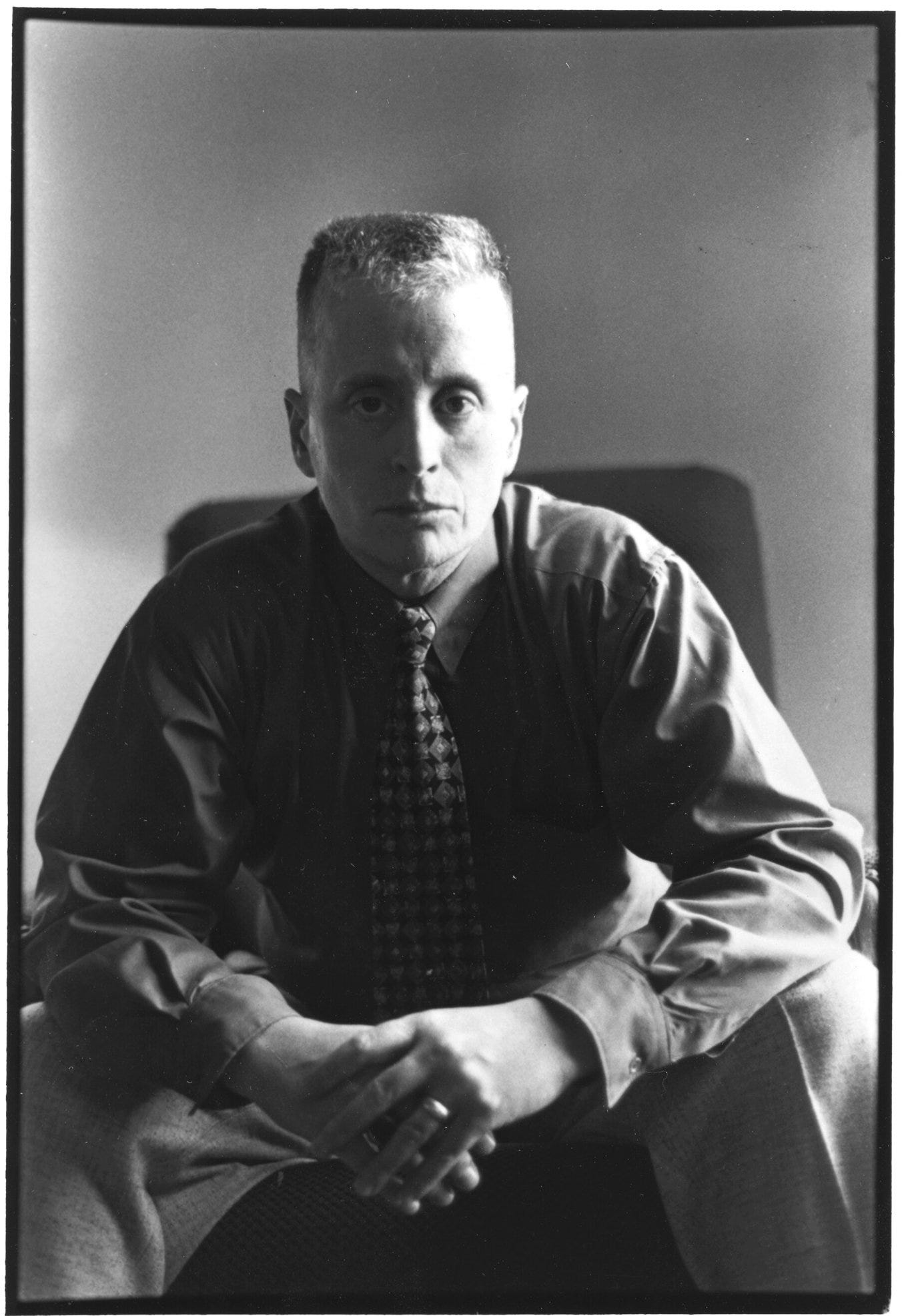

I first read Stone Butch Blues by revolutionary communist Leslie Feinberg (pictured up top) in my mid-twenties. At the time I was a cross-dressing prostitute, a masc4masc straight-for-pay who went to work in lipstick and stripper heels and came home to a butch who hated me for it (though she was happy to share the money I brought back with me).

I hated me for it, too. I didn’t know what to do about my gender, how to meaningfully connect it to my job and the class shame that came with it, or how to transcend it in order to truly trust the nascent gay family developing around me. I didn’t understand why I could be out and still feel afraid. I didn’t know how to reconcile my trans feelings with my femme instincts, or my desires (at the time and in that place, femme4femme and butch4butch were viewed with much more distrust within the community than they are now), with all the rules around what I thought it meant to be gay in the right way.

Blues was the first book I ever read that honored butchness without denigrating femmeness, and that celebrated femme strength without placing it in opposition to other gender expressions, or reducing it to straight capitulation. It was also an antidote to what I now see as the mid-aughts’ virulent strain of reactionary transphobic rhetoric that manifested as discourse around “masc privilege” and (cis) femme supremacy. Blues was the first book I ever read that depicted the natural, yet intentional, solidarity between poor and working-class queers of all gender expressions and races, and between butches and femme working girls in particular. It carefully resists the replication of bioessentialism in its exploration of the butch/femme dynamic without shying away from the bioessentialism, trans/misogyny, homophobia, and racism that sometimes deploy it as their smokescreen. Blues is not perfect, but it was so far beyond anything I had been exposed to, including anything I read in the one or two gender studies classes I’d taken in college, it was nothing less than a paradigm shift for me, because for the first time, I could see a historical precedent for people like me and my friends, a document of what existed prior to, and somehow survived, police repression, heterosexual violence, the AIDS epidemic, and centuries of poverty and disenfranchisement.

There is such an intense loneliness to thinking that one is the first, but I promise you that none of us ever were.

I don’t remember any butch working girls in Blues (though I could be wrong about that), and at the time, I didn’t know anyone else like me—boy by day, girl by night—but I knew for sure that if Leslie, or their avatar, Jess—a white, working-class butch—met me, they would welcome me as I was. They would not mistrust or fetishize me, as other sex-working women (especially, though not exclusively, the straight ones) sometimes did; they would not be infuriated by my painted nails and cheesecake photoshoots, as other butches and mascs sometimes were, especially when they wanted to fuck me. The honesty and vulnerability needed to show the reader how Jess, as Leslie’s stand-in, has their consciousness raised, again and again, by the generosity of the people around them—the queers of color, the sex workers, the femmes, the drag queens and transsexuals, the butches who love other butches, and yes, straight workers, too—inspired me to think more of myself, and of more than myself. Alienation was inevitable, but isolation didn’t have to be.

If I had the courage—and I had it; we all do—who I was could be more than a description of who I fuck and what I wear and how I move through the world: It could be a basis for organization, solidarity, and class struggle.

“Surrendering is unimaginably more dangerous than struggling for survival,” says Jess. This was as much a revelation to me as the realization that I could be a transsexual as well as a dyke, that one did not cancel out the other, as much as cisnormativity insisted otherwise.

Blues also showed me it was possible to view stone sexuality, leathersex, and other adaptive means of intimacy as a Truth, without losing hope for something truer, if that is what one desires. As they write in gratitude to the femme lover who cares for them after they are violently sexually assaulted by the pigs, “You treated my stone self as a wound that needed loving healing.”

The femme is careful in how she touches them; she knows, from her own experiences with vicious sexual correction and from her wisdom as a femme lover of butches, when it is safe to do so, and when it is not. “You didn’t flirt with me right away,” writes Leslie/Jess, “But slowly you coaxed my pride back out again by showing me how much you wanted me. You knew it would take you weeks again to melt the stone.”

I can’t read Blues’ scenes of mutual care between gender freaks without weeping, or remembering how painful it is to come home in search of that tenderness from your partner—your body bruised, or your will transgressed—only to have her despise you for your need because it reminds her of her own.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial.

🖤

crying it’s fine