In late 2019, Stephen Ira invited me to read at one of the NYC release parties for Ellis Martin and Zach Ozma’s We Both Laughed In Pleasure: The Selected Diaries of Lou Sullivan, alongside Cyrée Jarelle Johnson, Jamie DiNicola, Chris Berntsen, An Duplan, Serge Rodriguez, and Stephen himself. It was a beautiful celebration of an important book, a revitalizing sharing of work on “transmasculinity, intimacy, and freedom,” as the flyer put it.

This week, I’m posting the essay I read that night here on DAVID, which I’ve tinkered with since then, because it’s one I enjoyed writing and reading, and because it’s an integral part of one of my favorite memories from my first year in New York. Though it’s tempting to get back up on my soapbox to rail about the rights of trans youth, what with Everything That’s Going On Right Now1, today I would rather revisit a fond memory and leave it at that.

I was once a normal girl with a normal family. Like other normal families, mine watched The Godfather movies on Sundays after church.

With so many kids around, epics like Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, and Francis Ford Coppola’s iconic series were an interactive experience, a time to workshop our Brando impressions and scream along with the script, unless we were silently bearing witness to the occasional, excruciating simulation of heterosexual coitus. We all loved Michael Corleone, but I loved him most of all, so sometime in early high school, my dad brought home another movie he thought I’d be interested in.

Sidney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon (1975) stars Pacino as Sonny Wortzik, a character inspired by John Wojtowicz, who became notorious for knocking over a Brooklyn Chase to fund his lover’s sex-change operation in 19722. For the first time, I saw Pacino as an actor rather than as a character, and I fell in love all over again, watching Afternoon on a loop while I traced the black-lashed eyes on the VHS box cover with my fingers.

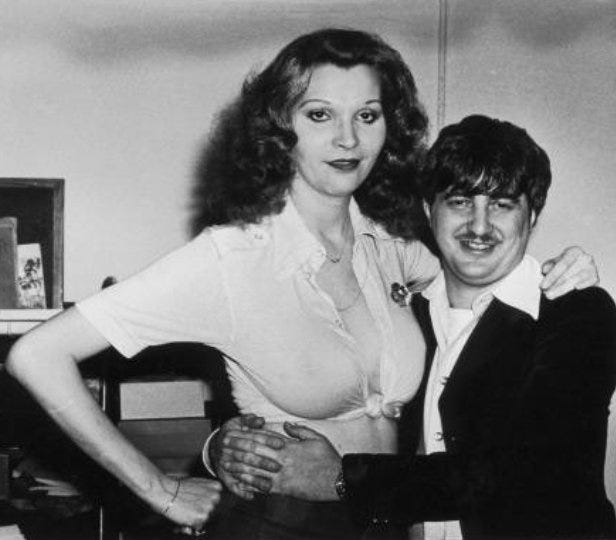

Pacino’s face is narrower than that of Wojtowicz, in whose mugshot you’ll find a lipbitten beefcake for whom De Niro might have been a better casting. Pacino’s skinnier, too, but in Afternoon he dominates the screen with his coal-black hair, strung-out skin, sweat-stained dress shirt. His discomfort is electric, contagious, as he waves his white hanky, arm wrenched to his side, shrieking “Attica!” just a little too shrilly at the bystanders surrounding the bank. Pacino was no Wojtowicz, who these days occasionally pops up as a conflicted trans Twitter thirst trap3, but I thought he was the most perfect man I’d ever seen. I coveted him, knowing without understanding that my puppylove dramatics could reassure my dad without either of us needing to think about why he needed reassuring.

I was not a cultured kid, and I did not grow up in cultured homes. Though I read widely, I still believed fervently in my Bible and the conservative talk radio I listened to before and after school. We had internet by that point, but I didn’t take much advantage of it, preferring to use the computer wedged between the kitchen table and kitchen sink to write stories in Word. My love for Afternoon was unanchored, a movie I had as much context for as I’d had for medieval Mesopotamia when I saw Aladdin (1992) for my first trip to the movie theater. I didn’t know what Attica was or why Sonny was screaming about it, much less about the massacre of incarcerated people that gave the word its power. I didn’t know why I wasn’t disgusted when Sonny is revealed to have a trans girlfriend, though I knew I was supposed to be.

The revelation of the pillow-lipped Leon—a character based on Wojtowitz’s lover, Liz Eden, and played by cis actor Chris Sarandon—kills Sonny’s crowd cachet, tanks the NYPD’s grudging respect for his daring, and dooms him as an enemy of the state. The carnival atmosphere ignited by Sonny’s anti-cop antics, which before earned him the sporting tolerance of the pigs, plummets like a Coney Island roller coaster. Afternoon dims as the day fades to night, the happy bystanders gone hostile as the feds kick off their plan to bust up the hostage situation created by Sonny and his stone-faced associate, Sal (played by John Cazale, another Godfather alum).

As much as I loved Afternoon, and as confident as I was that it was okay for me to love it, the entrée of Leon always made me uncomfortable. I didn’t think of either him or Sonny as gay men, though that’s how we’re meant to see them. When the cops allow Sonny a phone call with Leon, he talks to him like he talks to his cis wife: coldly, distantly4. Sonny is childish, angry, distracted; a shell of a small-statured man (at 5’7”, Pacino and I are the same height—almost short for a man and almost tall for a woman). Sonny’s a failure of a man because of his emotion, his desire, and yet he is still a man—in fact, his maleness is what makes his desires reprehensible. It’s seen as degeneracy, but his humiliation is also his mainstay in the midst of the biggest fuckup of his life. With Sonny, Pacino made failed maleness seem possible in a way that I, a normal girl, found inexplicably intoxicating.

Afternoon could have easily been a professional debacle for Pacino; Lumet said later that as far as he knew, no major male star had played gay in a movie before5. In his portrayal of Sonny Wortzik, there couldn’t be a whiff of faggotry about him, not if the audiences of the time were to accept him as their antihero. Pacino pulls it off, counterbalancing his frantic rage with either an asexual solicitude for or a virile impatience with the people around him. Even though he is committing a federal crime on behalf of his “gay lover,” as Leon was referred to for decades after Afternoon’s release, Sonny’s concentration on getting what he wants, on his desire, takes precedence even over the feeling presumably underlying his motive to commit it in the first place. Despite the crossed stars of Sonny and Leon, Afternoon is first a crime drama, a bank-heist flick, a man’s man’s movie. There’s little room for love here, and what tenderness there is feels as purloined as the cash Sonny came for.

Sarandon’s Leon, on the other hand, must be a faggot, as if to make up for Sonny’s homosexual emptiness. Cast instead of trans actress Elizabeth Coffey because she didn’t look like what straight people thought a transsexual ought to look like, Sarandon went on to be nominated for an Oscar for his role in Afternoon; though she eventually got her surgery, paid for with the money made from a movie about a crime committed in her honor, Eden died of AIDS complications in 1987 at the age of 41. In a 2014 interview, Sarandon noted, to my ears with some bitterness, that while many gay people over the years had thanked him for portraying a version of Eden, he had never been sought out for congratulations by “transgender” people.

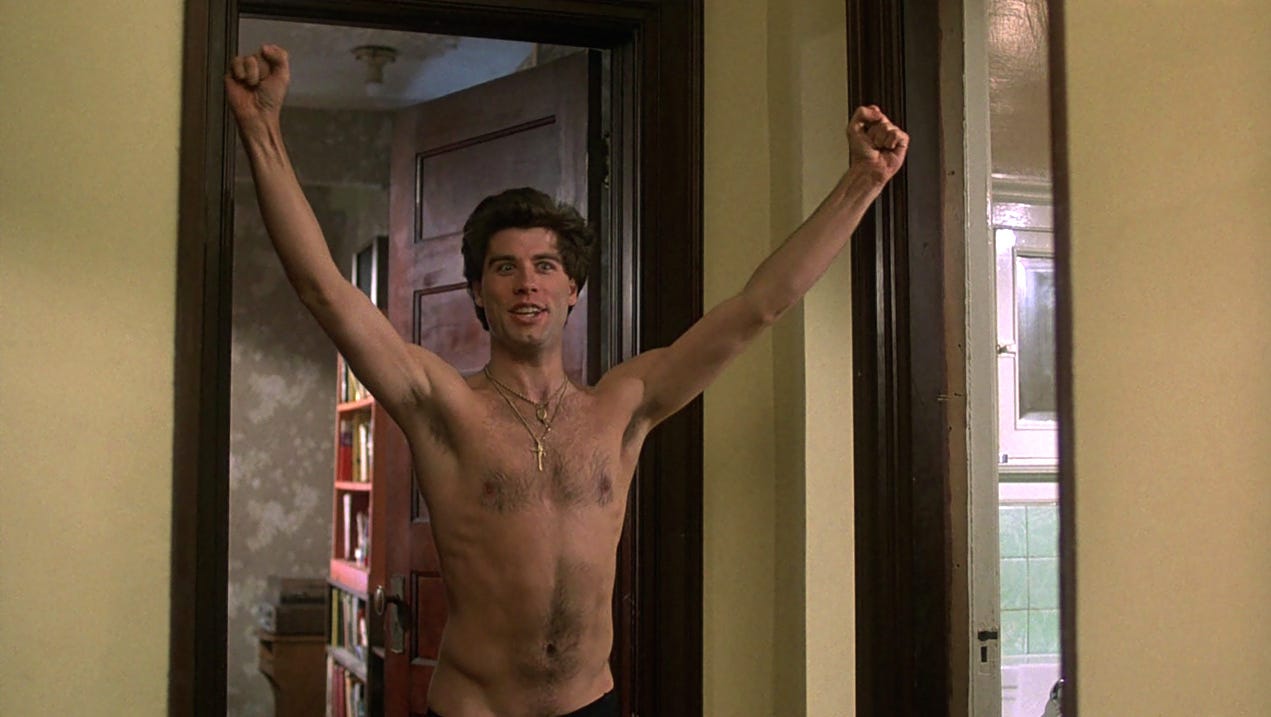

But I was not a cultured kid—I didn’t know about any of that. I didn’t even know that trans people existed outside of the movies. They were as real to me as the Mafia or New York City. All I knew for sure was that Pacino was the man I ached to have in a way that kissing or touching or even sex, of which I lived in terror, didn’t seem able to satisfy. Wanting him felt like the way I’d always wanted men, and the members of NSYNC, and the boys I went to school with, and the boys in my apartment complex, and the person I sometimes dreamed about. It felt like that scene in Saturday Night Fever (1977) when John Travolta marches out of his bedroom in his underpants chanting “Attica!” just like Pacino, at once embodied and aspirational and more than a little bit gay. It felt like that. It felt normal.

It wasn't just that I thought Pacino was handsome. I believed that his was the kind of handsomeness that everybody else could see. When we made PowerPoint presentations about someone we admired in my computer class, most us picked people we wanted to bone. I set to work downloading jpgs of Pacino and his 70s shag, convinced that my feelings about him were no different from those of the girls downloading Leonardo DiCaprio or Orlando Bloom.

It wasn’t until much later, when I was no longer a normal girl, that I saw what most other people did—that the ratty, wet-lipped little guy was a legitimate actor but in the vaguely repulsive model of Nicolas Cage or James Spader, whereas in my eyes he had been a Pitt, a Washington, a Clooney. It’s a misunderstanding that reminds me of a gag from The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. When he tries to pass as straight, Titus’s closeted boyfriend puts a picture of Tilda Swinton on the back of his pickup to better blend in among his coworkers at the construction site. The gag lands because the boyfriend’s heterosexual math is sound yet fails to add up, and everyone knows why except him.

In 2013, indie filmmakers Frank Keraudren and Allison Berg released The Dog, a documentary about Wojtowicz’s life. In its viciously homophobic and transmisogynist review, the New York Times undercut its own attempt to demonstrate “how profoundly sensibilities have evolved since Mr. Wojtowicz robbed the bank.” Afternoon’s affective shift signals for us when it has given up on humanizing, even endearing to us, Pacino’s two-bit bank robber. Though by all accounts a rat, a mob henchman, a woman abuser, a bigamist, and a narcissist, Wojtowicz’s claim to fame—the reason the freakshow still had juice more than 40 years after he robbed that Chase—remained his abnormal desire.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial.

Subscribe to support our mutual aid project, GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, a bimonthly advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.

Not that coverage and reportage aren’t important! I recommend Jules Gill-Peterson, Grace Lavery, Harron Walker, Chase Strangio, C. Riley Snorton, and Melissa Gira Grant as a few writers, scholars, and reporters on the ~trans rights beat.

The year of The Godfather’s release. Serendipitously, Wojtowitz and his colleague, Salvatore Naturile, went to see it in a Times Square theater for inspiration. According to this, Naturile, also known as Donald Matterson, planned to finance his sisters’ removal from foster care.

Like Wojtowitz, Afternoon’s Wortzik has married his transsexual lover while also being married to a cis woman, committing—at the very least—the crime of bigamy.

Pacino grew a mustache for the role because that’s what gay men were doing in the seventies, but Lumet said it “looked terrible.”

Share this post