In 2018, David Cronenberg said, “If movies disappeared overnight, I wouldn’t care. The cinema is not my life.”

Tracing the advent of the internet, streaming services, and the Disneyfication of the moviegoing experience to one of its logical conclusions, Cronenberg went on to say that the big screen, “is shattering into a million small screens.” Like the human body—his oeuvre, his specialty—cinema is “evolving and changing,” a process that can’t happen without destruction.

I don’t stray far from writing. It’s what I do. Occasionally I collaborate with other kinds of artists (historically, photographers and editors), but generally speaking, I stick with what I know. Still, I’m moved by Cronenberg’s view of medium as a means to an end, one that does not vanish when that medium changes. For Cronenberg, the movie theater is “the cathedral that you go to where you commune with many other people”; the Holy Spirit inspires architecture, but does not require it. Perhaps watching a movie on an iPad, he suggests, is transforming the filmgoing experience of yore to one more akin to reading a novel. We may have our concerns about how this compartmentalization can affect the nature of our communion (I certainly do), but to diagnose it out of hand as some kind of inherent loss is shortsighted.

This acceptance of change is unsurprising coming from the man famously willing to track sensation across genre, format, and technology. I think a lot about eXistenZ (1999), which while one of my least favorite Cronenbergs strikes me—with its Boomer-ish director’s generous curiosity about the home videogame, at that point still an unserious Gen X pastime—as almost courageous in a way that earlier films like Videodrome (1983) or The Fly (1986) are not. His movies are “voyages,” as he puts it in the article above, whose prime directives aren’t scaring people, but to provoke “philosophical thought.” Cronenberg’s unfailing curiosity reminds us that the ship’s captain comes with us on the voyage, too.

This perspective is indicative of the Buddhist detachment Cronenberg has cultivated in his old age and, perhaps paradoxically, of his artistic prioritization of pleasure. I admit that this may seem counterintuitive. Like this is the guy who made the car-fucking movie (no, not that car-fucking movie), the guy whose fixation on mutation, destruction, and pain is what put him on the map1. Like this is thee body horror guy we’re talking about here. What about “trauma incarnate as soulless goblin children in matching tracksuits” says pleasure to you, bitch?!

In Sensational Flesh: Race, Power, and Masochism2, Amber Jamilla Musser summarizes Foucault’s stance on SM as a strategy for moving homosexuality from an identity-based category toward “a way of being.” As Foucault wrote, “The idea that bodily pleasure should always come from sexual pleasure as the root of all our possible pleasure—I think that’s something quite wrong.” SM, Foucault goes on, insists that “we can produce pleasure with very odd things, very strange parts of our bodies.” Musser writes that SM “redraws the lines between pleasure and eroticism,” destabilizing the privileging of genitally based sexuality for something bigger, queerer, and more free. While formally resembling violence, SM is actually resisting it3; for Foucault, it “reorganizes the body to emphasize pleasure rather than identity or discipline; it offers tangible corporeal freedom.” After decades of organization, activism, and theory, many of us today can at least parrot rhetoric like “kill heteronormativity” or “smash the gender binary,” those “pleasures” have been built to crush us, and which we now recognize are to be interrogated. Why is it that we struggle so much to extend this critical lens to other pleasures and, by extension, other pains? There is more than a handful of binaries to be smashed!

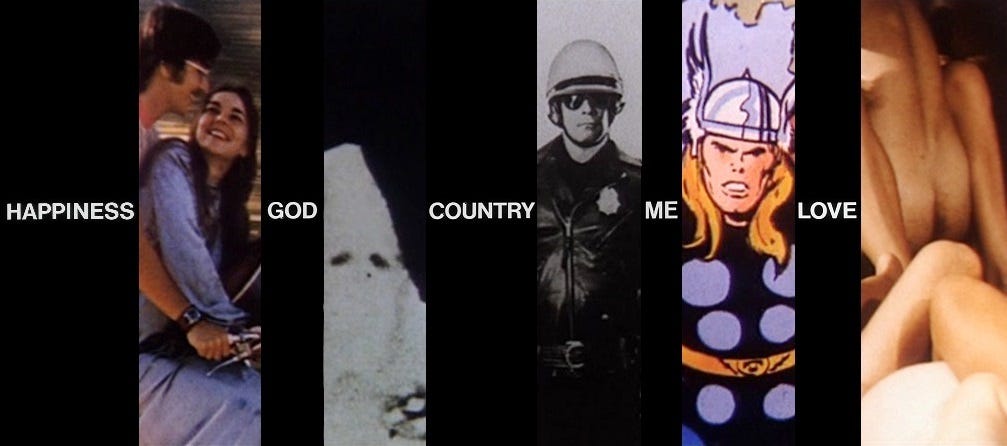

In Cronenberg’s career-long focus on pain and horror among the more accessible joys of filmgoing, we see an artist greedily rooting around in pleasure’s almost endless, and almost entirely unrecognized, capaciousness for pain. It is not an act of perversion to spotlights the metal fetishists and neogynephiles, but rather a commitment to pleasure, the pursuit of which we are trained to take for granted as natural and intuitive. What’s more, that commitment, like SM, is a communal one, and therefore, like the movies, a space for communion.

It occurs to me that in both their communality and their misrepresented vitality, both SM and David Cronenberg’s films resemble fungus: the self-annihilating, self-feeding, self-sustaining churning of old bodies into new flesh and back again.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial. Preorder their second novel, X (Catapult, 2022).

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, an advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

These things are not inherently shallow or debased, of course, but “horror = lowbrow” is one of our hoariest chestnuts.

Recommended by Zoé Samudzi :)

As much as Adrienne Rich, et al, insist otherwise.