Some spoilers of Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half (2020) ahead.

I started wearing men’s clothes when I was in college. I made the swap strategically, as I didn’t know how else to signal to other people—to girls, but also to boys?—that I was now gay. Wife pleasers and flannel felt good, but seeing them on my body did not. They didn’t fit right, just as women’s clothes had never fit right. But they did feel closer to right than women’s clothes had, with the added benefit of not having been forced on me. They also seemed to clarify me for others’ benefit: Whereas before there was simply something off or awkward or ugly about me, now there was a legible problem on which to fixate. Let it never be said that I would sacrifice clarity for comfort.

As I stared down the barrel of HRT, I considered myself lucky to have dressed like a lesbian for so long, which meant I wouldn’t have to go through the hassle of a wardrobe overhaul. There was no need to go to a new section of the store, nervously trying to parse vanity sizing1, or to face for the first time the anxieties of cross-dressing in public. Compared with the expenses of trans medical care and document changes, plus the less direct costs of decreased job security and the “pre-existing condition” of transsexuality (all pricy, sure, but not to the tune of $150,000 as our venture capitalist friends might insist), new clothes were a drop in the bucket. Nevertheless, it was a relief to have one less thing to worry about.

As I’ve started to see what’s known by some as masculinization happen to my body, the type of clothes I’ve been wearing for over a decade have begun to fit better, emotionally and otherwise. The inverted triangle tattooed on my ribcage is now more than a gay cliche: It’s a simulacrum of my new shape. No inverts here, ladies!

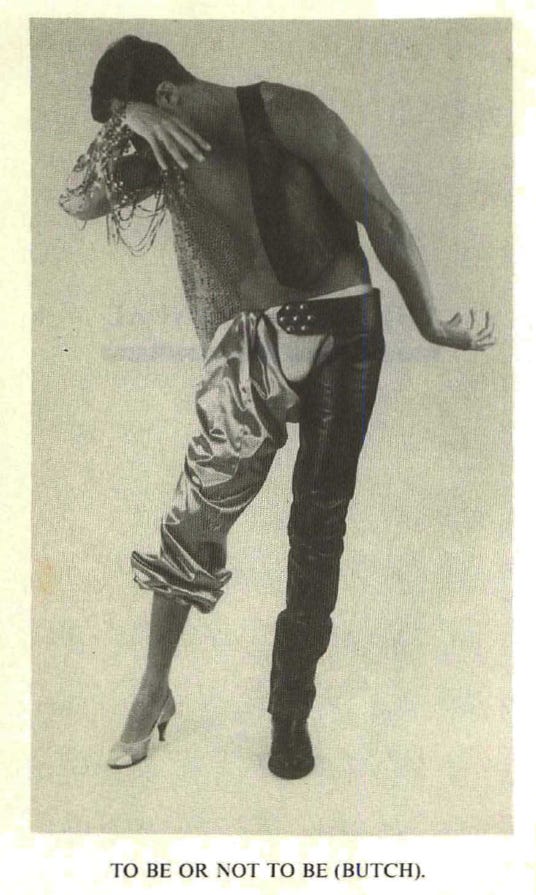

But if I thought that would mean I wouldn’t want new clothes, I was wrong (as I have been about so many things). The butch uniform that one of my sisters jokingly refers to as TOP BUTTON!—button-ups and hoodies completely fastened, an insecure overdressing combined with the wistful illusion of breastlessness—doesn’t feel like it fits me, either. I dress like a lesbian, I thought with dismay as I peered into my closet from a cyclone of dysphoric anxiety last week. The same clothes that had once made me clocky in one way now made me clocky in another. It’s funny, the way that solutions create problems.

As someone who is not a man, do I want people to think I’m a man? Mostly no. My most attainable fantasy is to blend in, around straight people, anyway; to escape the notice that has sometimes been so frightening and alienating. With all respect due to genderfucking—something I enjoyed when I was younger and less broken—I don’t want to do it anymore. I can’t. Cissexism, both external and internalized, is traumatic. These days, anything that doesn’t explicitly bear the stamp of having been manufactured For Men2 feels like a tell, a scarlet letter. I think the homophobia and transmisogyny of tabloid kerfuffles around straight male celebrities wearing dresses or Gen Z lads painting their nails is pretty obvious, but it’s strange to fight my resentment for the growing (race- and class- inflected) freedom that cis men have to do things I didn’t even get away with as a girl.

The more frequently I pass as a man, the more my old fears about passing, and what that might mean for me—as someone who has not ever identified as masculine, let alone a man—diminish. Beneath is not a crater, but a garden, beautiful and hostile and alien (like Jeff VanderMeer’s Area X), lush with new insight into the violence of binary gender and our collective inability to escape it.

About a year ago, I wrote a DAVID series about David Cronenberg, in which I described my experiences with certain kinds of passing:

As a white queer person, I should make it clear that passing as straight or cis doesn’t map 1:1 to any other kind of passing, particularly with regards to race... There’s plenty of actual scholarship about the similarities, differences, and relationships between concepts of passing, about which I’m not even an amateur…I can speak to my experience with passing as a transsexual, but it’s impossible to do so in a vacuum.

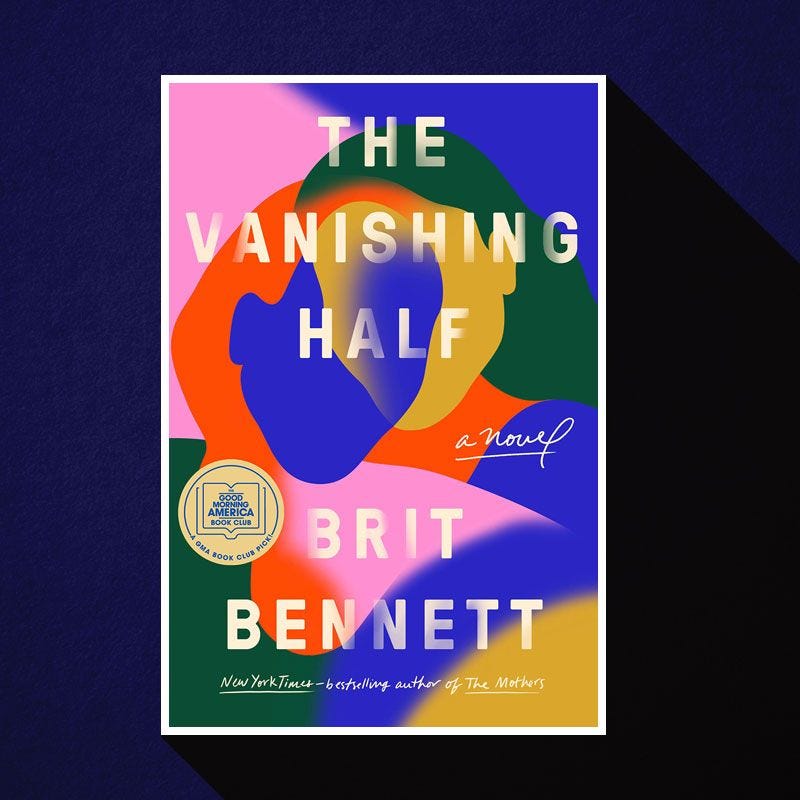

Writing about Harlem Renaissance novels like Passing (1929) and Plum Bun: A Novel Without a Moral (1928) for that entry, I remember making a mental note to look for contemporary stories about passing by black authors, which I never got around to. I was reminded of it again when, earlier this year, my agent sent me a copy of Brit Bennett’s highly praised The Vanishing Half.

Over the course of its 352 pages, Half grows subtly, almost shyly, from a book into a cinematic experience. An intergenerational novel spanning nearly half a century, it follows the lives of twin sisters Desiree and Stella from their tiny hometown of Mallard, Louisiana—populated almost exclusively by light-skinned black people—to New Orleans and Los Angeles. In Mallard, where “nobody married dark,” the twins, with their “creamy skin, hazel eyes, wavy hair,” fit right in. It’s the rest of the world that finds them ambiguous, which they discover after running away to New Orleans at the age of 16 to make their own way.

Desiree ultimately marries a dark-skinned man, has a dark-skinned daughter, and returns home to Mallard to escape her abusive husband, where she struggles to make ends meet for her family. After being mistaken for a white woman at her job, Stella decides to permanently “cross over.” Gone without warning, Stella marries a rich white man and raises an affluent white daughter, disappearing into another life, the comfort and safety of which her twin can only dream.

Some reviewers of Half think Bennett doesn’t dig deep enough into her characters’ interiority. From the NYT: “Some depth is sacrificed for the swiftness; the book doesn’t burrow into the psychology of its characters so much as map the wages of artifice, fracture and loss across generations.” And it’s true that there are so many key characters in Half, so much distance in time and space to cover, that there isn’t enough time to feel as if we know any one of them as well as we would like to.

But in a sense, I disagree with that take. One of the strongest aspects of Half is Bennett’s weaving of the somatic experience of trauma into her characters’ lives, using their bodies’ defense mechanisms to color and inform their desires and decisions. This is a function of her empathy for all of her characters, including the often-hard-to-empathize-with Stella, whose decision to abandon her sister and integrate into whiteness is held up alongside the nightmares, terrors, and dissociation of a young life shaped by vicious antiblack violence, including the horrific lynching of Stella and Desiree’s father when they were young children. Even in her most intimate moments with her white husband, who doesn’t know Stella is black, “she saw the man who’d dragged her father onto the porch, the one with the red-gold hair.”

I think Bennett’s adroitness is most impressive in the subplot around Reese, the boyfriend of Jude, Desiree’s daughter who moves to California on a UCLA running scholarship. I’d heard that Half had a transmasculine character, and was curious to see how a cis author like Bennett would write him. Tense at his introduction—protective of this fiction of Bennett’s mind—I slowly grew impressed by the way she depicts him and the struggles that he faces as a young black trans man. Any questions of authenticity that arose for me, of which there were one or two, came from a place of my own ignorance; my cultural knowledge of black queer and trans communities in LA in the 70s and 80s amounts to a hill of beans.

By the final page—a scene which shows us Jude and Reese swimming “under the tangerine sky,” neither hiding their skin or their scars from the other, and which deftly feints melodrama with its hints at both finality and forever—I was surprised to realize I had come across a cis writer of a transsexual person that I not only didn’t loathe, but rather liked3. What’s more, Bennett accomplishes the extremely daunting task of addressing and contrasting more than one passing discourse in a single book without conflating them.

Which is big. Huge, even. In a post-Dolezal context with skyrocketing animus and violence against black people and trans people, and especially black trans people, Bennett’s use of fiction to write with nuance and compassion about the distinct yet interlinking phenomena of raced and gendered passing without using one to demonize trans people or demarcating the other as an implicitly white (and therefore violently antiblack) category, is a triumph that I wish would get more recognition. For a book with so many laurels already, it’s the very least that it deserves!

David tweets at @k8bushofficial. Subscribe to support our mutual aid project, GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, a bimonthly advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth.

I imagine this is harder for the girls, since US women’s sizing is notoriously cuckoo bananas. What the fuck is a size 8? Bitch I’ll kill you.

It’s not lost on me how gender accumulation consumerism and fast fashion participate in these anxieties of representation. I read with interest this recent post from Alex V Green on the phenomenon of “he/theys” and our various means of “aesthetic, affective, and communal dislocation from capital-M masculinity.”

I’m still waiting on a review of Half by a black trans person, or at the very least someone with more insight into the cultural background in which Reese and Jude live. That being said, to write the character, Bennett, “drew on some nonfiction writing by trans men from the ’70s and ’80s, and…consulted with a friend who’s a scholar of trans lit and history.”

Share this post