Last weekend, I wore my leather mask while a small group of friends inserted needles into my upper thighs. One of my friends practiced their suturing skills in the same place, my first time being stitched up without an injury to justify or lubricate the process. Once bleeding, I invited my friend to hit the little wounds (needles and knives hurt upon entry, but punching the open flesh feels good and unfortunately kind of sexy), and in a burst of excitement, Jade slapped it so hard that my blood sprayed across the adjacent coffee table, staining an empty cocktail glass and the side of an upholstered chair.

Everyone laughed. Blood is always fun, perhaps because it coagulates—and thus becomes something else, something sticky and much less beautiful—so quickly. I witnessed all of it from inside a dark and tenebristic place, a perspective I compare to that of a blinkered horse, an animal I spent a lot of time with in my childhood; or to a cat, who lacks the muscles necessary to see what’s right in front of her nose.

Recently, I’ve begun to wonder if part of the mask’s potency for me is connected to learning how to protect myself. For all its power to numb, lull, narcotize, the mask is a technology that requires present, intentional negotiation. It’s not merely off or on, hooded or unhooded—as I said last week, it goes in all directions. The way I experience sensory deprivation changes as I do, and as I mature as, at this point, a light bondage fetishist. And as I have learned how to use this tool, it has changed me.

For example, I think that using the mask has allowed me to become less squeamish, or in other words, a little more brave. Generally speaking, I don’t like gore, real or simulated. In movies, if there is any risk of seeing skin broken, I cover my eyes and wait for my girlfriend to give me the all-clear. I can inject my own testosterone, but I won’t put funtime needles in myself, like most players I know can, and I always used to refuse to watch the needles or scalpels go in. None of my business. I’m not a masochist because I like pain, but despite it, and as we all know, watching the painful thing happen makes it ten times more painful. It’s hypocritical and cowardly, but since I was providing the generous service of getting other people off on my blood, I allowed myself the treat of engaging with my fear in this silly, lopsided way.

But masking has changed me. In a mask that limits but doesn’t eliminate my vision, I can now watch the needle go in, though it’s still very unpleasant (and I retain my right to be squeamish with movies. Remember that awful scene in The Talented Mr. Ripley with the knife in the bathrobe pocket? UGH. Stuff of nightmares.). There’s something about the mask that both buffers sensation and estranges me from myself. I am, briefly, another person, or perhaps another critter, one that must squint to parse the movements, lights, colors, always a step away from understanding. The bad thing is not happening to me! I would posit that it’s dissociation in the same way that communal-based masochism is self-harm, especially because most sadist don’t like to let you get too far away in your hot-air balloon of endorphins. Then they can’t witness your pain, and where’s the fun in that?

There are passive and active ways of protecting oneself. The younger version of me harmed myself indiscriminately and compulsively, in instinctual escape from physic discomfort; the current version of me allows hurt (not harm) in controlled environments with people who care about me and my physical and emotional safety, people who require that I don’t turn off, but stay present with them. This doesn’t mean that I/we don’t get high, or that I don’t go to subspace, or whatever you want to call it. It means that victimhood, in our scene, is the fantasy. It is not the reality.

Protecting oneself is a skill that many of us are forced to unlearn as very young people, but if we are lucky, we can master it as adults. It’s an uncomfortable skill to acquire, because self-protection requires agency, presence, responsibility, and accountability, to others as well as ourselves. It requires mindfulness and the ability to interpret the signs and signals of one’s body, which is much harder to do for many of us to do than it sounds. To protect oneself, one must assert oneself, thereby becoming vulnerable to having one’s boundaries crossed and one’s body hurt. Self-protection acknowledges the risk of harm, and for many, this is not possible without first doing a lot of healing.

I suppose it might seem contradictory to talk about self-protection as a masochistic type, myself, but “clear cut” works best with scalpels, not affective and emotional experiences. Like all pleasures, my time with SM is crepuscular and juxtapositional (dare I say liminal?). We know that our bodies don’t strictly differentiate between kinds of arousal. There is fascinating potential in these twilit worlds—a contrast, a push-and-pull that both destabilizes and reinforces binary understandings. Perhaps this is why the noir, as a genre, is so compelling for me.

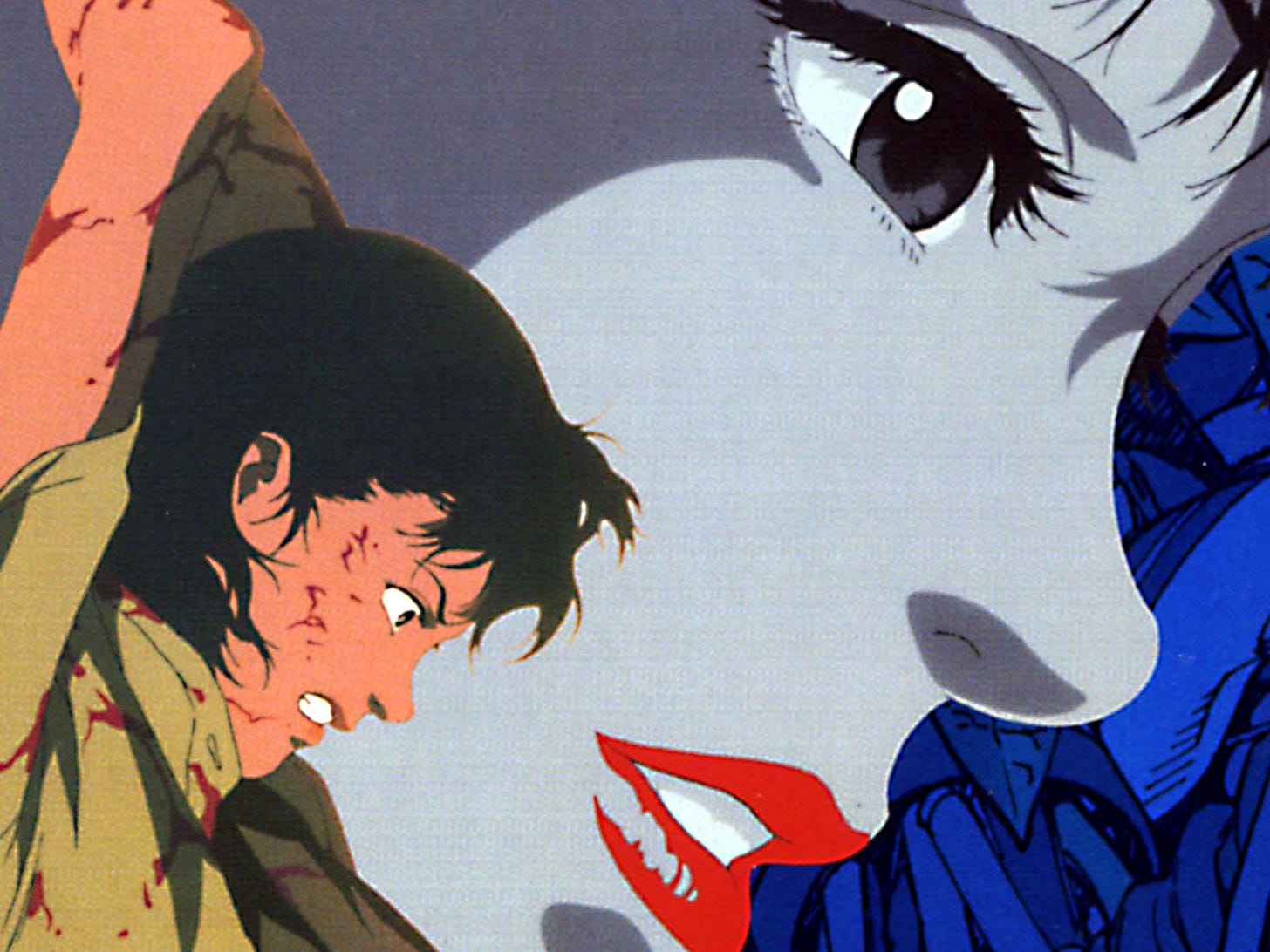

Before we watched Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue together, Jade explained to me how much its imagery and themes were lifted by Darren Aronofsky in Requiem for a Dream (2000) and Black Swan (2010). Though I hadn’t seen either in years, as we sunk deeper into Perfect Blue, the resemblances became obvious. As she and I discussed films being “in conversation” with each other, I kept thinking about other noirs whose shades I sensed in Kon’s masterpiece, the fascinating artistic through-lines over decades, countries, movements, media, artists, and narratives: Preminger’s Laura (1944), Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940), Curtiz’s Mildred Pierce (1945) (starring my “longsuffering/cunty Crawford”), not to mention Polanski’s Chinatown (1974), Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), Amenábar’s Abre Los Ojos (1997), Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001), the literature of James M. Cain and Sarah Schulman and Manuel Puig. Funnily enough, the line between homage and ripoff has resonance with the line between self-harm and realized masochism.

But I was not able to pursue all of these threads, to have the sorts of discussions and arguments I love having with my girlfriend about movies, because Perfect Blue’s rape scene1—the one so famously replicated in Requiem for a Dream—took me out of myself, away from myself. My squeamishness extends to simulations of sexual violence as well, and I have learned over the years that my body will not tolerate bearing witness, even the false kind. I was so frustrated: It was not only just a movie, but an animated movie at that! But then, as I said earlier, our bodies aren’t great with the subtleties of arousal.

I finished Perfect Blue, but it finished me, too. All of the standard stuff that happens to me when I get triggered happened, and instead of getting to enjoy thinking about the film’s ugly politics, or the internet as a (then-) new technological representative of the unconscious, or male directors’ genius for finding ways to nominally acknowledge women’s interiority while somehow making the violence against all the more dehumanizing, I had walk my body down memory lane, an ineffable, totalizing process that rejects reason and drinks blood. Most frustrating of all, I knew that, had I protected myself, it wouldn’t have happened. Watching it with my girlfriend, I had known the risks of a movie like Perfect Blue, but even prepared, my body called my bluff.

How unfair it is, I remember thinking, that to be safe I have to limit the art that I enjoy. Is that what self-protection is? Choosing not to participate in life to forestall the aftershock of trauma?

When I sat down to write this entry, I figured that it would be the end of this little series, but now that I’m here, I think there’s more. Until next time, I guess.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial.

One that Kon apparently went on to regret.