David

A mise en abîme in serial

When I chose the name Davey for myself in my mid-twenties, I was inspired to do so by an acquaintance. The guy in question was very cute and very boyish and very small for a cis man, and I liked these things about him. I wished that these were qualities that were true about myself. He spelled his name Davy, which I also liked, but for reasons having to do with my OCD, I decided that my version would be D-A-V-E-Y. When I eventually changed my name officially, I left the space for “Middle Name” blank, thus cutting my legal name down to two words with five letters on both sides. Davey Davis—how satisfyingly symmetrical!

Davey also shared certain sonic similarities with my deadname, which for some reason was also very satisfying, even if no one who only knew me as Davey would ever be able to make the connection. Finally, Davey had an inexplicable X factor, a little bit of Marge-Simpson-with-a-potato: I just thought it was neat.

Though I suspected I would be using this new name for the rest of my life, I resisted the urge to devote too much time and energy to choosing it. I knew myself well enough to be sure that if I dwelled on, stewed over, perseverated about my options—which were my paternal grandmother’s maiden name plus a few tried-and-true white transmasc classics, à la “Adrian”—I would whip myself into an anxiety attack, followed by weeks of an angsty fugue, only to land on a choice that I would immediately regret.

Better to take a name I knew that I more or less liked and just roll with it, I decided. No writing it out in my composition book, encircled with heart doodles, as if replacing my surname with that of a schoolyard crush. No informal polls of my friends. No formal polls on Tumblr, the social platform du jour. No test-drives. No Plan Bs. In a way, I went about renaming myself with a method that got as close to my original naming as I could without opening a baby book with my eyes closed and planting my finger at random; I was making a decision that would have a not insignificant effect on the rest of my life almost passively, as if I could circumvent buyer’s remorse with the by reassuring myself that I hadn’t tried all that hard anyway. At 23, I was still managing my OCD like any unrehabilitated perfectionist: If you never try, you’re never disappointed.

By thinking as little as possible about my new name, and the identity that it circumscribed, I believed I could forestall the taint of meaning—of context, history, bias, problematic, evidence, violence, desire, etc.—upon it. I was wrong about that, of course, as one tends to be about intellectually dishonest impulses. In the years since then, I’ve learned that while there are some things I still like about my name—its androgyny, its simplicity, its relative singularity—there are plenty of things I don’t like about it.

When people see Davey written down and then see me (which happens not infrequently to someone with a debit card) or hear my voice (which happens not infrequently to someone who regularly interacts bureaucracy’s administrators over the phone), they often think they have misread or misheard. A woman, they think, could not have this name. People often think they heard me say Daisy, or that Davey, which had seemed fairly straightforward to me when I chose it, is pronounced Dah-Vee. (These days I pre-empt with the unglamorous but effective: “Davey. Like gravy.”) There I was, thinking that my new name would make more sense than my given name! It turned out that, even as androgynous, as simple, as original as I thought it to be, Davey is rarely legible on my body. What else is new.

I still go by Davey, but when I began medical transition two years ago, David began creeping in after a friend, another trans person, began affectionately referring to me that way. I had been named again, but I knew, right away, that this time it had been done right. Though my parents had planned to name me Zachary had I been born with different genitalia, David is very much the sort of name that could have been on their short list. There are men in my family named David. David is the name of a king much beloved by the god I was raised to worship. Inasmuch as white American evangelical Christians can be said to have a coherent culture, David belongs in it, certainly more than my (surprisingly secular) deadname.

That’s when I began collecting Davids. If Davis is one of the world’s most common last names, David and its iterations must be even more so. I keep a list on my phone. I often talk about someday writing a book to house my Davids. “A Bluets for Davids,” I offer as my pitch, imagining an essay collection about all of the Davids I’ve been exposed to, the people and characters that predated or inform the David(s) that I am now.

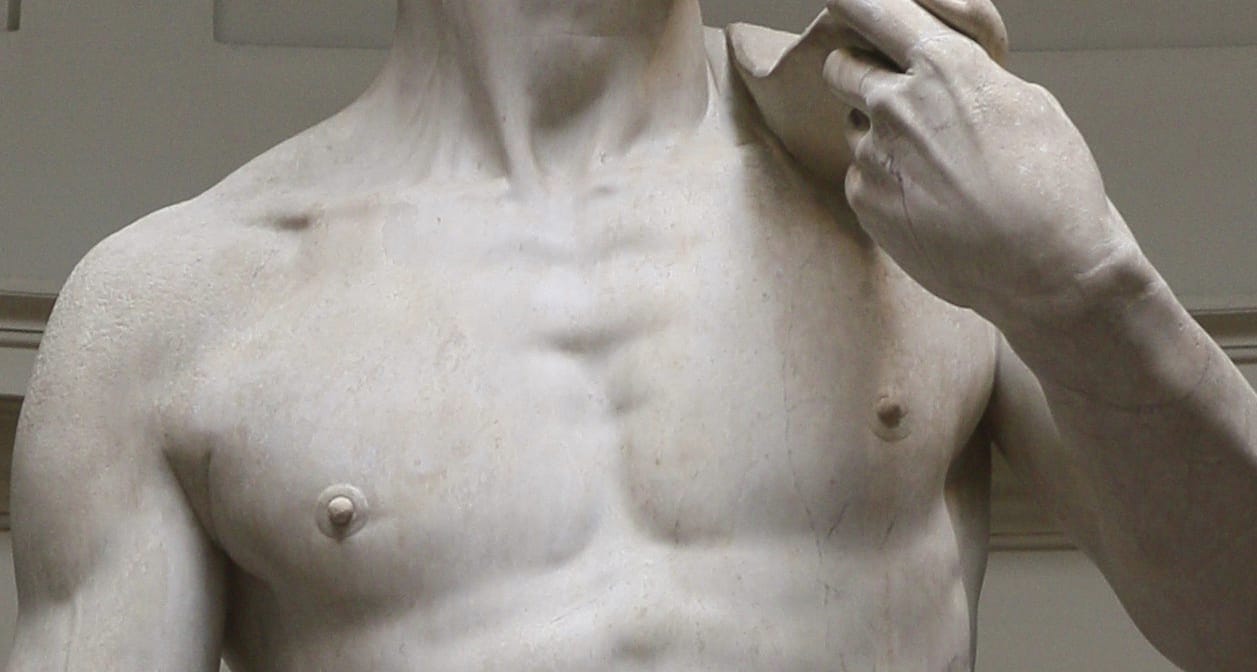

I don’t know if that book will ever happen, but in the meantime I’ll be writing about my Davids here. There will be an entry about David Lynch, another about David McCall—Mark Wahlberg’s antagonist in Fear—about the mousy, dreamy boyfriend of Darlene from Roseanne, about Davids Hyde Pierce and Wojnarowicz and Koresh, about Davids sculpted by Michelangelo, not to mention an assortment of asshole artists (Fincher, Foster Wallace, Bowie).

Maybe you’d like to read about them? I don’t know. Like Davey was at the beginning of all of this, David is a hopeful experiment.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial.