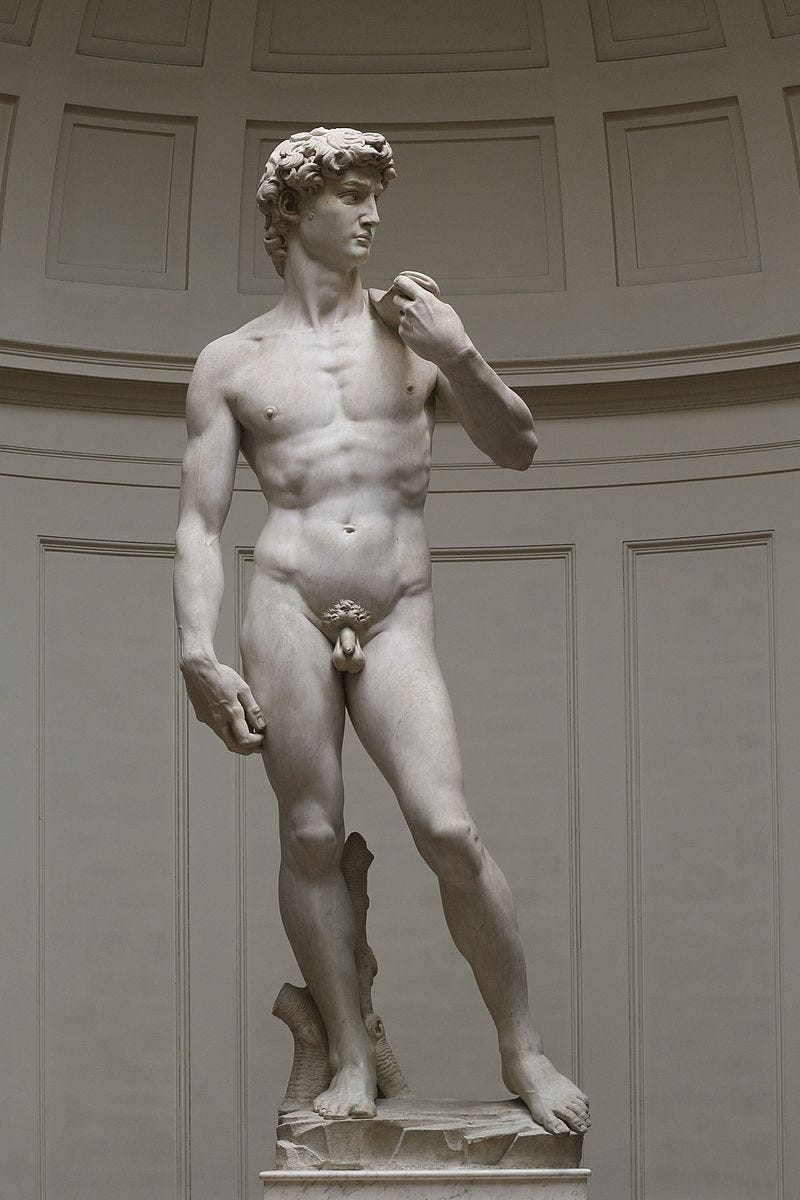

Michelangelo's David

David. Like the statue.

When I was looking at Michelangelo's David last night, it occurred to me that the statue and I have the same nipples. Makes sense. Both sets were made by human hands, after all.

It’s fun to imagine Michelangelo in the operating room with the infamous Dr. Hazen. I’m sure that they would have a lot to talk about; I assume that plastic surgeons are as much preoccupied with beauty as sculptors. Most people plucked from the Renaissance and set down in the twenty-first century would probably have a meltdown at the first lightbulb, but I bet Mike would be scrubbed up on the observation deck in no time.

Lately, I’ve been having dreams about an ex-boyfriend of mine. F had been a good friend for a few years before we started dating around the time I came out, so though our romantic relationship was short, it was intimate and intense. He would have been the first to admit he was a small-town guy. He wanted to settle down, get married, buy me a house; my mom said racist things about him here and there, but fantasized about the mixed children we would make for her. Everything could have been simple.

I was in love with F, but I was also in love with a butch who he hated, and he stormed out of my apartment when he found us together. The last time I saw him, a year or two after that, I told him I wanted to have my breasts removed. He got angry. I stood up from the park bench where we were sitting and walked away.

In my dreams, we’re in bed together again. He’s lying behind me, reading the scars on my back. He traces them with his finger. My body has changed so much since the park bench, but he isn’t angry now. He’s curious, a little bemused. His fingernails are the same shape they were ten years ago.

But when I wake up, F is still 3,000 miles away, still married to a cis woman who looks vaguely like me ca. 2011. He was beautiful and I wanted to look like him. I miss him.

The problem and appeal of beauty is that it is doomed, soon buried. A defeatist wouldn’t even attempt to be beautiful—transsexuality is inherently optimistic in that way. “I wanna look like what I am,” Lou Sullivan wrote in his diary, “but don’t know what someone like me looks like.” In cases such as ours, extant reference points are useful, for us and for our surgeons, who are only human after all, despite their god complexes.

In Dennis Cooper’s Closer, David is the name of a beautiful, empty boy who has a sexual encounter with a romantic little sadist named Steve.

About his George Miles Cycle, of which Closer is the first of five novels, Cooper told Artforum, “I wanted to write about disorientation and acts of sex and cruelty, and try to articulate things that are impossible to articulate in language, like desire and the incoherence of violence and love.”

After his encounter with Steve, Beautiful David is mowed down by car in a freak accident. Beautiful David, once described as “a perfect mess,” is now just a mess, dead meat that’s “shredded like paper.” He doesn’t last, unlike our statue, though he has the advantage of being a natural David—not like me, or the erstwhile hunk of Tuscan marble known as “the Giant.” Still, violence wins out over beauty. Sometimes the latter requires the former.

It may resist articulation, but violence still demands our attention, and our compulsive interrogation, in a way that rivals even beauty. In the preface to Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War, Nobel-prize winning journalist Svetlana Alexievich writes, after 20-odd years of covering war and disaster, “I don’t want to write about war again.” And yet she does. She wrote the whole damn book (and a bunch of others on the subject), quoting Pushkin, in bewildered explanation: "To write or tell the whole truth about oneself is a physical impossibility." And yet she tries.

Robert Glück wants to know: “What kind of representation least deforms its subject?”

No matter how faithful, representation alters the source material, changing the Giant into the Giant Killer. Sometimes representation is the first mirror we’ve ever seen, if we’re lucky enough even to get that far. Sometimes those lucky ones leave evidence, like Sullivan or Red Jordan Arobateau, another trans writer who lived during the time before, when “our label was not gay”—it was crazy, or nothing at all.

To be David, both the statue and the Cooper twink, would be good. What must it feel like, to have been created by a gay man, and then destroyed by one?

David tweets at @k8bushofficial.