What I've been reading and watching

on trauma plots: Jamie Hood and "Nickel Boys" (2024)

Since I last wrote one of these, I’ve watched a score of films, read seven or eight books (not including my own, as it moves through the copyediting stage), saved eight or nine interesting articles/essays to my “Articles/Essays” spreadsheet, and seen one Broadway play: “GYPSY” starring the sensational Audra McDonald as Mama Rose1. I wish I could write about all of it, but considering that I’m in the thick of the Valentine’s Day Extended Universe™ that is being polyamorous and, you know, everything else, I can only do so much.

I’m not really a trigger-warning type of person, but the book and film I’m reviewing today both depict graphic, terrifying violence. I recommend them very highly, with the caveat that I found them challenging to read and watch, respectively. Please take this into consideration before reading and be gentle with yourself when you can.

What I’ve been reading

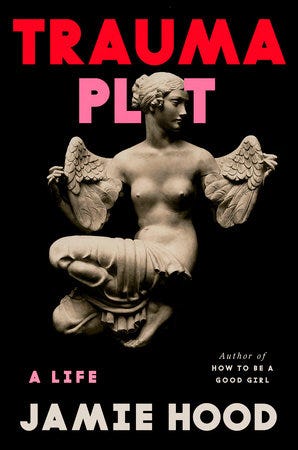

Trauma Plot by Jamie Hood (out March 25)

With her second memoir, a beautiful and formally original meditation on misogyny, memory, and art that’s at turns harrowing, lovely, and sharply funny, Jamie Hood makes a powerful case for trauma as a worthy literary subject. Challenging Parul Sehgal’s infamous takedown of the so-called trauma plot, Hood examines the now-trendy conflation of the “first-person industrial complex”—i.e., what happens when you convince marginalized writers that, as Jia Tolentino once put it, the “best thing they have to offer is the worst thing that ever happened to them”—with women artist’s personal stories of sexual violence. As Hood writes:

“What troubles me…is the wholesale idea of our relation to writing as unexamined, crude, and lacking in competence with self-reflexivity, humor, and play. Like there’s no reason to write about trauma except to make a buck. Like if you talk about having lived through something awful, that’s all you’ve ever talked about or ever will. Like you have no agency inside a story you yourself choose to tell.”

Grounded in her graduate studies of the modernist confessional, and in particular the work of her beloved “suicide girls” Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, and Anne Sexton, Trauma Plot is in search of time lost to PTSD. Like a hall of dissociative mirrors, Hood’s series of past selves—speaking to us in the third, second, and first persons—navigate school, work, relationships, and therapy while fighting to live lives of pleasure and meaning under the specter of traumas repressed, relived, and constantly anticipated. Readers of Hanya Yanagihara’s novel A Little Life, one of Sehgal’s subjects, tend to clump into two camps: those who feel that its “accursed” protagonist’s suffering is realistic, and those who don’t. Hood’s own experiences with rape, poverty, substance (ab)use, and sex work, and the ambient violence that subtend them for women and queer people in particular, throw this schism into stark relief. “For me,” she writes, “[A Little Life] was one of the only novels I’d read that saw how pervasive intimate violence is in our lives, and how shadowy, how stigmatized, how great the pressure to stay stoic in facing it, to weather violence without complaint.” How can women writers who have undergone the unspeakable2 pursue “self-making” when their very lives have rendered them “unliterary?”

I’ve loved Jamie’s writing, particularly her criticism, for years now, but I didn’t want to read Trauma Plot, knowing it heavily featuring the epithet “rape girl,” which she used to disparage herself in the wake of the grievous violence done to her. I knew it would be too difficult, a suspicion confirmed within the first few pages; while interesting, engaging, and intellectually rigorous, Trauma Plot is a book I had to force myself to begin and to finish, crying on the G train in the process. Once, I literally threw it away from me, as if it were on fire. While I honor Jamie’s fear and despair, it’s her fury that gave me what I needed to make it to the end. Perhaps that’s what got her there, too. As she writes near Trauma Plot’s conclusion,

“But I have to remember I’m not writing this to be believed. I’m writing to open space in myself for other books, to offer solace—I hope—to others who’ve lived through this. I can’t write for my worst readers, and there’s no amount of evidence that would satiate people, there’s nothing to do or say that could make a person ‘good enough’ as a victim. It’s why people like us best when we’re dead. As if death is the only proof possible, like: oh dear, see what happened to that poor girl, and now she’s gone. Better we can’t speak. Better our corpses be the books left behind us, interpretable to everyone but ourselves.”

What I’ve been watching

Nickel Boys (2024)

David Canfield compared RaMell Ross’ first non-documentary narrative to The Zone of Interest (2023) in the way it “reinvents the language” for movies about a “dark historical chapter.” I haven't read the 2019 Colson Whitehead novel on which Nickel Boys is based—about Elwood and Turner (Ethan Herisse and Brandon Wilson), two Black teenagers incarcerated in a boys’ reform school in 1960s Florida—but its literary influence is obvious in Ross and cinematographer Jomo Frey’s approach to visual storytelling. Making use of symbolic interstitials—Southern Gothic aphorisms like eerie country roads and unexpected gators—as well as surprising yet fluid inversions of perspective, Ross and Frey show us that much can be seen, and even exposed and revealed, when the eyes are averted, whether from fear, submission, or dissociation.

This is not to say that Nickel Boys is a work of misdirection. We see unspeakable, but unfortunately still see-able, acts of violence, primarily against Black children and young men. It made me afraid, disgusted, triggered, angry, and despairing. At one point I thought about leaving the theater, but something inside me said, “No, you must witness this, especially because you’re white.” But then something else inside me said, “Okay, that’s actually stupid.” While I did stay, I actually didn’t have to, white or not, and doing so didn’t do anything for the people who suffered the very real, and ongoing, injustices that Nickel Boys renders. When analyzing this work of art, I think makes more sense to think about what is gained—that is, what my body learns—by seeing and hearing it, despite myself.

If Nickel Boys had any lesson for me, personally, it’s that suffering together in acts of defiance is heaven compared to suffering alone. I think this is something that I know intellectually, but that needs to be known by my body, perhaps reiteratively, in order to keep it that way. If art can do anything, it’s preparing you to learn this lesson in real life, or reminding you of the times that you’ve learned it in the past. Because although Nickel Boys depicts a great deal of physical and spiritual abuse, some of its most wrenching moments are when a person reckons with it alone, whether because they are forced to, or because they cannot bring themselves to share it. Luke Tennie as Griff, a Black boy who is murdered for not throwing a fight with a white boy put on by the white man (Hamish Linklater) who runs the camp, gave such a powerful performance of loneliness that I forgot what that he was an actor; in the boxing ring, his cries of rage, frustration, and fear before making his fatal error (suicidal choice? overwhelmed mistake?) were almost more affecting than the more straightforward scenes of nightmarish physical brutality. Torture is dehumanizing, which is why people resist it even when that resistance leads to even worse suffering, if not death. But as Nickel Boys shows us, this resistance has its costs, in the present and far into the future, so much of it manifesting in isolation—the price of survival.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of fundraiser for Palestinians trying to survive within Gaza or relocate to safety. Gaza Funds is one place to get started.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

Jade’s Aunt Laurie got us tickets. Thank you, Aunt Laurie!

I love how Hood eviscerates this canard. “[T]rauma has a language; we just convince ourselves otherwise so we aren’t forced to face it. Or perhaps we’re convinced it’s unspeakable by those who wish us not to speak it, who know silence protects them. So someone says being gang-raped is ‘beyond’ representation, a statement that’s demonstrably untrue…I’ve written one hundred thousand words on my trauma. Is that unintelligibility? Rape effaced me and yet I speak it. It stole my face and my name, and I’m still fucking here. It remains in me. We live in rape’s presence, and its presence infests us. This pretense of wordlessness is a tool of the tormentor. It doesn’t serve.”