Uncle David is only one person

some of my unfamiliar genders

When I got to California, it had been over a year since I’d seen my godson. Though he’d been talking about his Uncle David at preschool, my sudden reappearance in his very home—to the euphoric groans of the German shepherd mix and the contented shrieks of his toddling sister—was an overwhelming development. Covering his eyes, he asked one of his mothers to serve as our go-between, ferrying him his hotly anticipated Christmas presents from my suitcase. Luckily I had played my cards right: the risky gift (a Peter Gabriel album for the family record player) was summarily rejected, but the safe bet (a Lego fire rescue boat) sealed our friendship forever. For the remainder of the trip, he stalked me through his mothers’ dusty, bookish house, the rattling Lego box clutched to his chest. Despite its linguistic construction, “Let’s build, Uncle David!” was never anything less than an order.

Prior to this most recent visit, my godson was unable to call me much of anything at all, so the title of uncle had always been theoretical, aspirational. It had been a somewhat queasy concession on my part—I wasn’t so sure I didn’t feel like an Auntie David. But you want to be a good sport when the people who care about you take a well-meaning stab at affirmation. And you also want to be mindful of your gender’s inconstancy (suppose I wake up some morning with a changed mind?). And furthermore you want to be practical about the clockiness of auntie relative to uncle on your androgynous body, especially considering how children’s voices tend to carry—almost as shrilly as the infantile peals they so recently were.

As usual, my pronouns were even more problematic than my name, though my godson and I were building our boat with such gusto that this didn’t come up until the second day of my visit, when I heard him refer to me as she while talking to his Mommy. I must admit that I drooped; at his age, children are too young for politely pro-social lies. But I soon noticed that he was alternating she with he, and so naturally, too, as if Bushwick’s proprietary blend of she- and he/theys were already on his radar. When I cuddled him, I was she. When I showed him how to load the tiny Lego gun with tinier Lego projectiles, I was he. Not that his style of gendering followed any recognizable binary—I was also he while I hand-fed his sister chewy bits of pan-fried tofu and she when I left my room without a shirt, as flat-chested as he was.

His Mama, the butch whose amorous notice dragged me out of the closet at 21, told me that she’d reminded him that Uncle David uses they and them, just like a few parents he knows from his preschool.

“And do you know what he said?” asked Mama, ashing her cigarette in a homemade ceramic bowl. “He said, ‘But Uncle David is only one person!’”

We laughed, impressed with his cleverness. Imagine a child still in Pull-Ups arguing about English grammar! Mama was surprised by his recalcitrance, but the they/thems my godson knows from his crunchy preschool, where all the boy students sport Prince Caspian-length curls, are safely cissexual. I’m the first person he’s ever met—or has ever built Lego boats with, anyway—whose gender is a mystery. Later, he pestered his Mommy about which bathroom I peed in; later still, when I unthinkingly deepened my voice in order to pass while buying something in a shop, my perceptive little angel wanted to know why Uncle David had done that. I kissed his golden head and told him the kind of lie of which only a much older person is capable: “You know, buddy, I’m not really sure.”

Though I had been steeling myself for my own conversation with my godson, I had an unexpected change of heart. Not only was this conversation unnecessary, but I had begun to wistfully wonder what it would be like if other people—adult people—could gender me as he did. One strategy for withstanding a child’s tediums and tantrums with some degree of dignity is to bear in mind how fleeting it all is. What if this is the last time they reach up, with wordless confidence, to be held? What if this is the final midnight feed, the ultimate diaper, the concluding cough-in-the-face? It won’t be long, I suppose, until my godson respectfully falls into line and uses the pronouns that are most comfortable for me while still being accessible to cis people. Like “Uncle David,” “they/them” is a queasy compromise I made not long after I met his Mama. It seems that my godson navigates all genders as he does the world: with a trust in his own perception that almost contradicts his sharp awareness of how little he knows. His certainty is unimpeachable, yet his questions are endless.

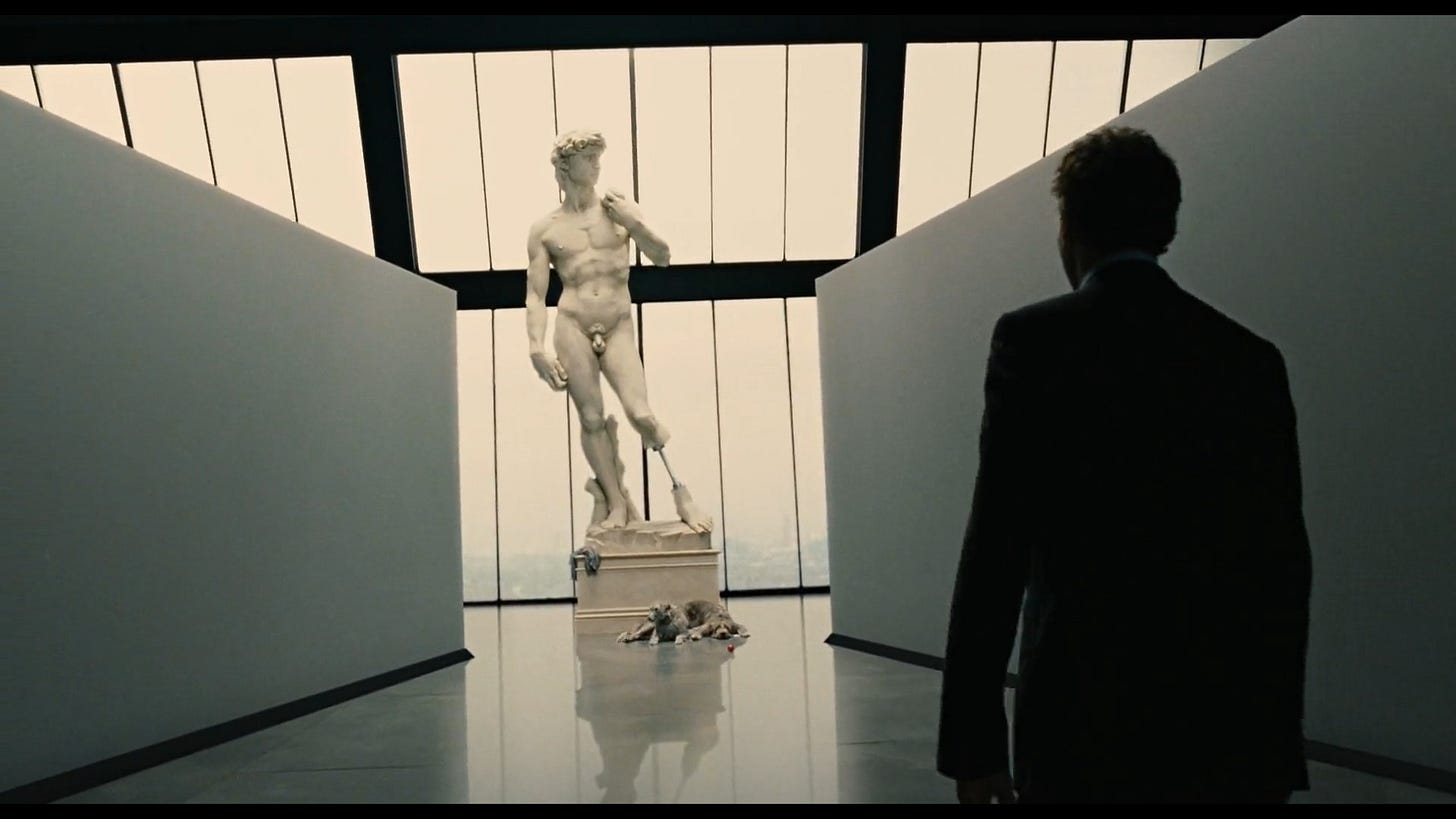

This change of heart was about more than feeling seen, if not always relaxed, in the presence of someone too innocent to do anything other than name the world as it comes to him. Watching my godson puzzle over me without fear, shame, or even urgency reminds me of the unfamiliar genders I encountered when I was a child, only some of which were disturbing to me1. Their mystery, uncomfortable but invigorating, splits the darkness of my oldest memories, a red-hot schism of time’s protective fugue: Tracy Chapman, who for years I imagined as the sunflower on the cover of her 1995 album New Beginning; Robin Williams’ brother-in-law in Mrs. Doubtfire (1993), a Castro gay cheekily referred to as Aunt Jack; comedian Suzy Eddie Izzard, whose Dress to Kill VHS my family would chase with Jeff Foxworthy tapes; and the beautiful RuPaul, who came on TV to tease, if I remember correctly, Chuck Lorre. “That’s really a man,” my dad told me, but I watched him admire her with his sunburnt arms folded uneasily over his chest.

Mama, who like me grew up looking gay in a place where people weren’t above accusing children like us of demon possession, is so gentle with her kids that it’s hard to believe she could have been raised in any other manner. One night while we were smoking, she told me about her son’s adoration for another uncle of his, a large and muscular cis man that he loves to gaze at, gently stroking his cheek with delicate, near-translucent fingers.

“Maybe he’ll be gay, too,” she said, and we laughed again, trying our best to appear indulgent. Though neither of us expressed it, we both knew that the other was reminding herself where she was and with whom; that she was not a child anymore and would not ever be again.

My readers and subscribers allow me to keep publishing work that’s mostly free for everyone, so thank you kindly for supporting DAVID. If you would like to support me in other ways, you can also like and share my posts, order my new novel, Casanova 20: Or, Hot World, or follow me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

While I didn’t much care for Abby McEnany’s Showtime series Work in Progress, her dyke insert’s confrontation with Julia Sweeney, the actor who played Saturday Night Live’s Pat character back in the nineties, was actually pretty cathartic for me.