I never slept well as a kid, always certain that something—a vampire, the devil, germs—was under my bed or outside my window. I’m not so old that an adult would have gotten the Sandman on my case, but I knew who he was thanks to the Chordettes’ “Mr. Sandman,” the 1950s pop song that briefly features the apparition himself (…Yes…?). By the 90s, the retro hit had acquired several layers of irony on top of its intended cuteness, meaning I was just as likely to hear it at the grocery store as I was in a horror movie like Halloween II (1981)1.

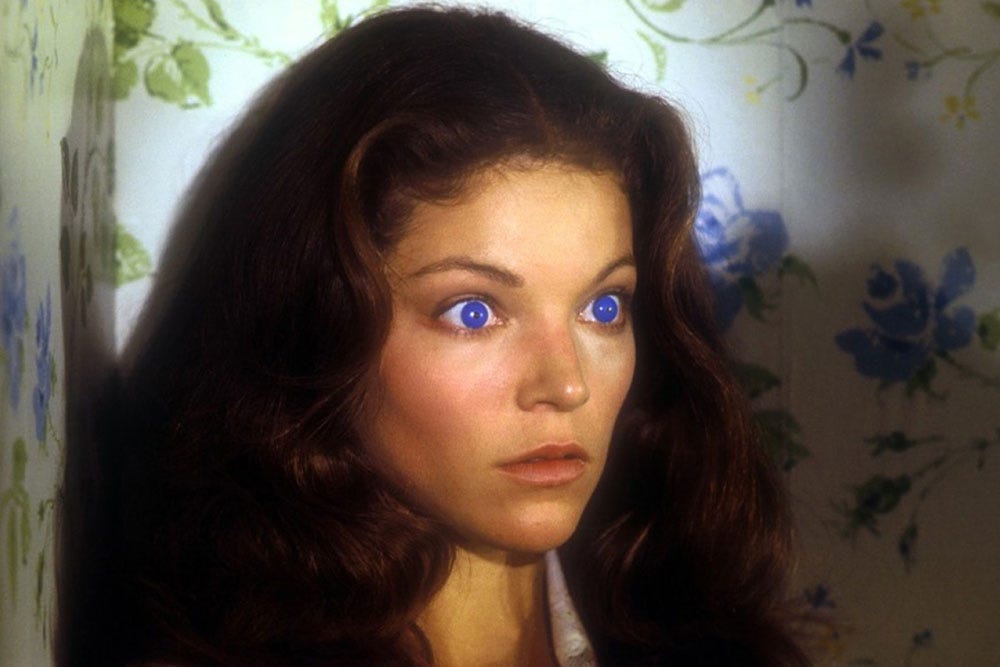

Like all folkloric monsters, the Sandman, a creature of Germanic and Scandinavian fairytale, was at one time more straightforwardly disturbing. After centuries of giving kids the willies, his entrée into text was with E. T. A. Hoffmann’s 1816 short story, Der Sandmann, as a “wicked man” who steals the eyes of children who won’t go to bed. The story is told by a character named Nathaniel, who as a child believed that his father was in thrall to the Sandman himself. As an adult, he has a memory of the Sandman threatening to take his eyes while his father begs for mercy on his behalf.

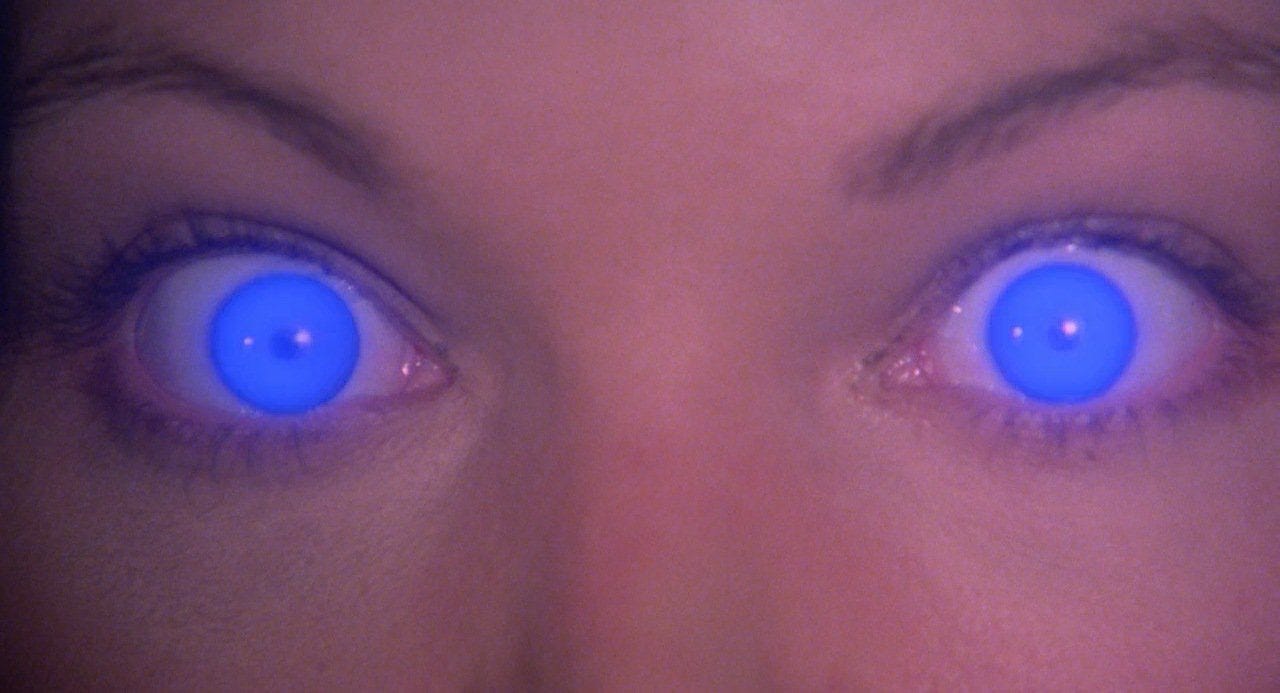

In Carol J. Clover’s Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film, she distills the “eye of horror” down to the organ itself as penetrator as well as site of penetration: the eye is both a weapon and a “natural and original vulnerability.” Here she quotes Freud’s writing on Der Sandmann:

“We know from psycho-analytic experience . . . that the fear of damaging or losing one’s eyes is a terrible one in children. Many adults retain their apprehensiveness in this respect, and no physical injury is so much dreaded by them as an injury to the eye . . . A study of dreams, phantasies and myths has taught us that anxiety about one’s eyes, the fear of going blind, is often enough a substitute for the dread of being castrated.”

I don’t remember worrying about my eyes in my childhood, but since developing panic attacks about two years ago, every other month I convince myself that I’m suffering the initial symptoms of an infection or disease that will permanently rob me of my vision. Last week, when the psychosomatics actually took shape in what was eventually determined to be a garden variety stye2, it was only years of practice, patient reassurance from my lovers, and my alprazolam prescription that kept me from becoming completely hysterical.

At the beginning of HRT, I began to experience a reversal of time more dynamic than mere regression. Fumbling my way through puberty3, I found myself brushing up against neuroses I had relegated to my twenties, teens, even my childhood. I kept aging, of course, but it was as if my path into the future was now doubling back through long-forgotten developmental milestones and the defense mechanisms that sprouted like flowers around them. Maybe these flowers grew from bulbs, which when peeled would reveal more bulbs inside, each enshrining its own abyssal bloom. Where to begin, in such a situation? Where to end?

For decades, I avoided my transness with dissociation. When I finally permitted my body to know this truth about myself (by this I mean the surgeries and the medicine, but also the acknowledging and accepting and entrusting of this truth with others), I gradually gained the ability to move both forward and backward in time—to remember my past rather than reside in it; to wonder about my future rather than merely anticipate or ignore it. (I don’t think the power of time reversal is unique to transsexuals. It can happen to anyone who begins to really feel their neuroses, which is the first step to really thinking about them4.)

Six or so years later, this freedom of time has granted me the capacity to regard my neuroses with some curiosity. Does my new fear of blindness resemble any other fears that I’ve had before? When and where did they come up? If it was during my youth or childhood, which adults were involved, and how? If these associated fears did resolve, what story did I tell myself to explain this resolution? Did it happen in the way that I had feared or hoped? With these questions, I pluck the neuroses from their respective places in time and lay them out next to each other for comparison, like budding flowers, like pages of text: how does today’s narrative inform yesterday’s, and vice versa?

With the help of this system, I’ve realized that my so-called fear of blindness is actually about something else (no shit!). When obsessing over what’s going to happen to me, I don’t really dwell on my prospective life as a newly blind person and the struggles that would entail, like learning how to walk or read in an entirely new way. Instead, I focus on the possibility of being informed (perhaps obviously but nonetheless crucially by a white-coated authority figure) that my eye, as I have known it my whole life, is done for. Over. Caput. It’s not its injury or uncertain future that terrifies me, but the moment of sickening revelation that these entail, a cliffhanging sensation that I associate with other kinds of dreadful anticipation, like wondering if I will pass in a bathroom or at work. My eye, my “natural and original vulnerability,” as Clover writes, leaves me open to those who may diagnose, clock, or revile me using their own eyes—more reasonable fears, certainly, than a sudden and random loss of sight.

A symptom of the trauma of becoming, Freud’s castration anxiety—a universal experience that takes place between the ages of 3 and 5—is associated with the fear of losing control, autonomy, and even life itself. If we put aside the idea that HRT marked the beginning of my adolescence and instead regard it as my birth, two years ago I would have been right on track for this psychosexual development.

Years ago, I started going to therapy because I wanted answers. In the last year or two, I’ve become interested in psychoanalysis because it refuses them altogether (“All analyses end badly,” as Janet Malcolm wrote). Anyone with an irrational, or even hysterical, fear knows that recognizing it as such usually isn’t very helpful. But there is something soothing, even encouraging, about seeing my fear for what it is: an expression of a mechanism that is deeply, inevitably human.

Thank you for reading and sharing my newsletter. Buy my books or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

Get a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content when you screenshot your donation of any amount to political prisoner Ángel, a butch lesbian, community organizer, and 2020 uprising defendant who is currently in ICE custody. She will not fight hir deportation to Chile, where she has not lived since the age of 7, but will need money to rebuild hir life from scratch. You can also send money directly to Loba-Cabrona on Venmo or $PunkWolfe2 on Cashapp.

As horror filmmakers well know, pop music deracinated from its context by time or juxtaposition can go from catchy to creepy really fast. Just as pop music gains a sinister new register over time, more “serious” music loses it, as Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” demonstrates.

My first and, god willing, my last.

Widely regarded as my second, which I’m not sure I agree with. The longer I’m at this, the more I feel that being forced to undergo the wrong puberty kept me locked in childhood. The TERF logics that infantilize white transmasculine people sure tell on themselves, don’t they?

Consideration being qualitatively distinct from anxiety’s spectrum of anticipatory affect: fretting, stewing, perseverating, fixating, etc.

“I kept aging, of course, but it was as if my path into the future was now doubling back through long-forgotten developmental milestones and the defense mechanisms that sprouted like flowers around them. Maybe these flowers grew from bulbs, which when peeled would reveal more bulbs inside, each enshrining its own abyssal bloom. Where to begin, in such a situation? Where to end?”

Beautiful, David