Life on the desert island

on your acts of creation

Years ago, when I was trying to decide if I should transition, someone suggested a helpful thought experiment: would you still want these interventions if you lived alone on a desert island, with no one around to see them change your body? Like every hypothetical, this one had an agenda, which emerged from the premise that anyone who sought surgery or hormones because of their social context could not really, truly want them1. To be authentic, this life-changing desire must have a deep and essential and perhaps even genetic origin, one that has as much to do with other people as your eye color. Only someone who would choose to transition while in total exile, it followed, could even approach worthiness of such a serious act of autonomy.

Only with time and medical transition did I come to really grasp the violence of this premise2. Today, I’d wager my rent check that if you polled the 99 percent of us who don’t regret transitioning medically, there would be no uniform, “correct” answer to this question. Even my own was split: I figured I would only want to be on hormones if I had to live in the world with other people, but if I had to go to that desert island, I would be as titless as the day I was born. In this sense, I suppose, the thought experiment was elucidating, but only once I disarmed it by subverting its premise. Had I taken it as intended, I would have had to add it to the web of emotional hairline fractures caused by the mountain of “well-intentioned” advice from cis family members, doctors, and other ghouls who had convinced themselves that their desire for my death was actually a sort of neighborly practicality. (Anyone who asks or compels you not to transition is communicating their preference: that you die. Internalize this, act accordingly, and you will be free.)

Clearly, a thought experiment such as this one is not designed for nuance or a world in which change—of circumstances, needs, or desires—is not just possible, but assured. Like most of what passes for “self evident” or “commonsense,” it’s designed to torture transsexuals for admitting to the social nature of our embodiment; for our deeply human and healthy need to be seen by other people, and not just ourselves, for what we are.

Life is hard, maybe especially for other people, so how can we dare to do more than merely endure it? In her indispensable new piece, “Deconstructing Creative Angst,” Charlotte Shane writes about the guilt that many of us feel when presented with the opportunity to “indulge” in the things that align us with ourselves—our interests, our passions, our art. Perhaps you, too, have found it easier to conceive of an existence of righteous drudgery and unremitting self-denial than grant yourself permission to seek comfort, relaxation, or curiosity as well as mutuality and justice. In a world where the distribution of cruelty favors you even a little bit, Charlotte writes, “[f]orfeiting creation may, subconsciously, appeal as an alternate penance.”

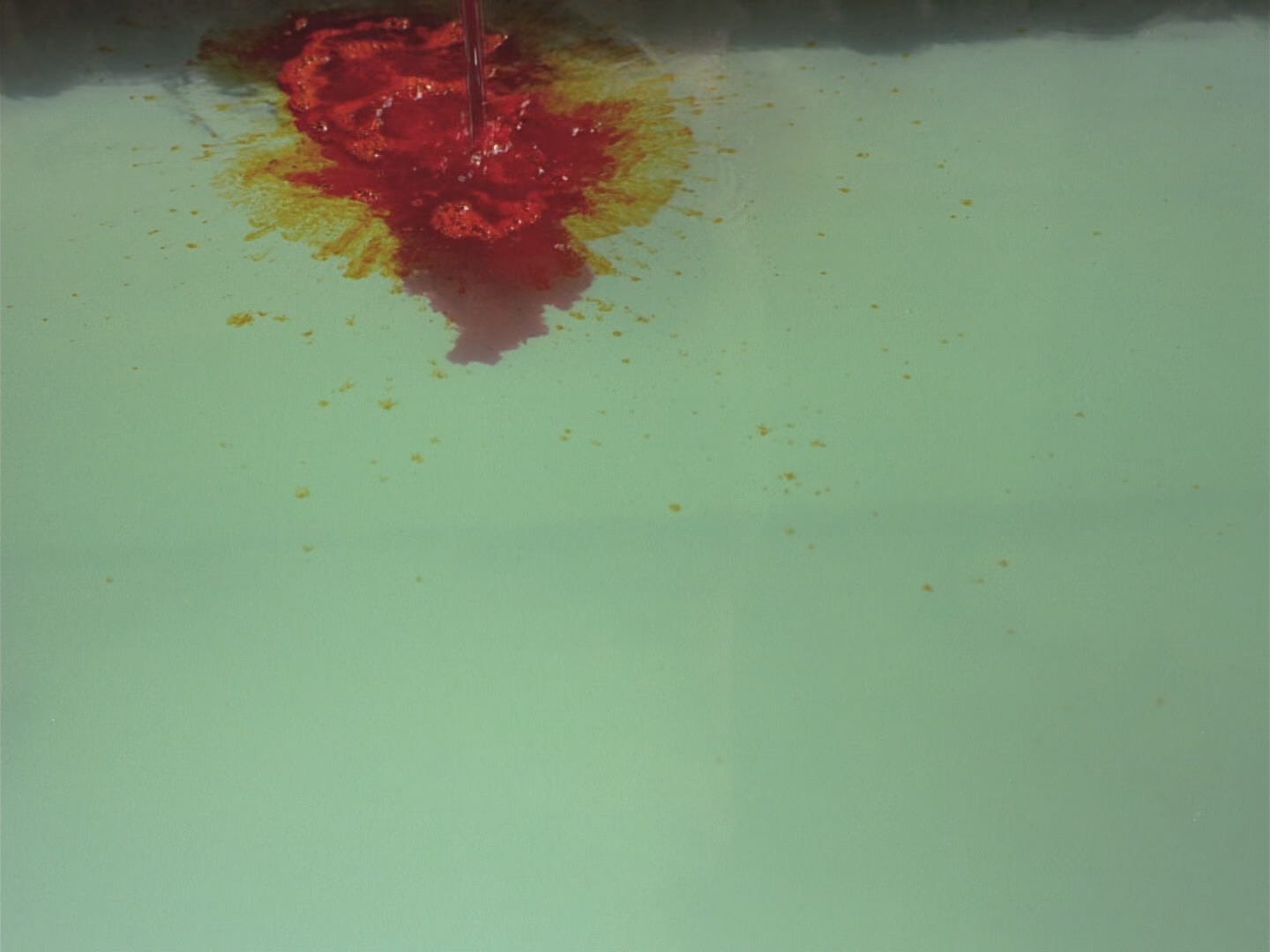

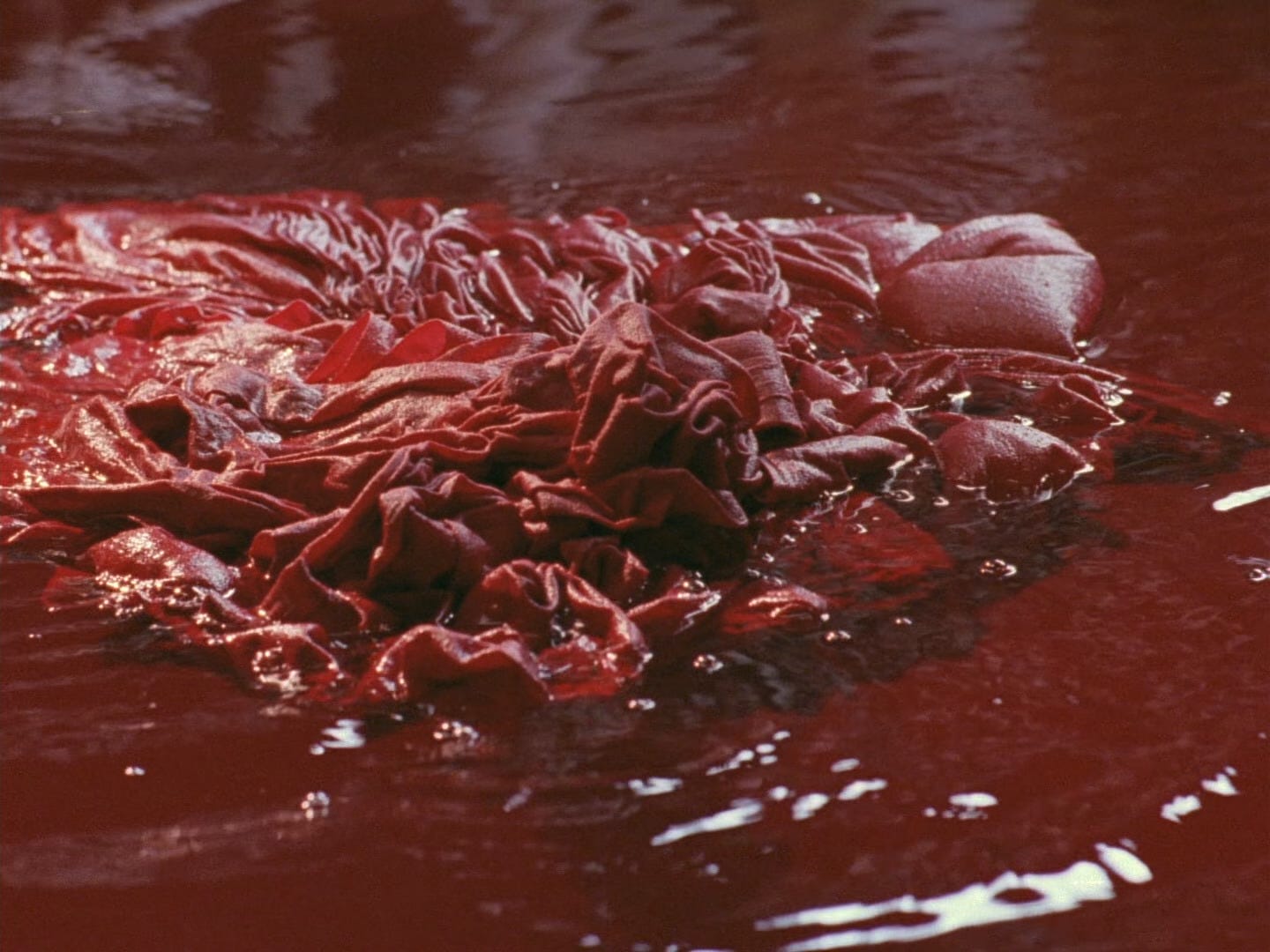

She’s talking about the irrepressible urge to create that many of us feel pressured to wad up and throw away, especially at “a time like this.” If you’re an artist of any kind, I highly recommend reading her piece in full. I also strongly recommend it to anyone struggling with the choice to transition, because I still can’t find the difference between my art and my transsexualization. These acts of creation are not just the ways that I’ve stayed alive, but the reasons why I’ve hung on3. They are what give this particular life its worth. Without them, I cannot think or be; without them, I do not exist.

It’s not like I didn’t try it their way. For years I attempted to participate in my elimination, cutting away the parts of me that needed and wanted, hungered and fatigued, lusted and wished, in accordance with the desert island logic, which kept me not just from transitioning, but from indolence and play, as well as more “useful” activities, like thinking and cooperating (and now we see, don’t we, that this distinction only reinforces the notion that there is a bad way to be, a useful way to wither and die?). By refusing my very life on the basis of this specious utilitarianism, I also refused my connection with other people. As a result, I was as useless as I was miserable. It continues to fry the fuck out of me that the kinder I am to myself, permitting my body leisure as well as the disciplined play of art, the more I am able to meaningfully, tangibly help and support my community! I must again quote Charlotte at an indulgent length:

“Here’s a question for everyone who writes, paints, composes, etc., and is haunted by a sense that they’re wrong (bad, selfish, irresponsible) for doing so: if you give up your songs, your art, your poems, what will you replace them with? Where does that energy go? Is writing or art-making in the top five most frivolous things you do? If you were to make a list of all the wasteful ways you expend yourself, would imagination or journaling or rehearsal be on it? What good things happen when you stop? What good things are prevented if you persist?”

In a recent Death Panel episode, Menominee Native organizer and movement educator Kelly Hayes talked about her new book, Read This When Things Fall Apart, a collection of letters to activists and organizers on the frontlines. I’m not an organizer, but I have been organized, and I was deeply moved by Hayes’s invitation to the restorative pleasures of rest and imagination to those hard in the paint, which begins with accepting that not being everything is not the same as being nothing. “This thing about ‘enough,’” she told Beatrice Adler-Bolton, “it only matters that me and my ideas aren’t enough if I’m alone.” If you regard your own sustenance as an unforgivable indulgence, how can your opinion on the sustenance of others be any more forgiving? Without yourself, there is no “everyone.” As Charlotte writes: “You do not have to solve a problem, let alone the worst problems known to humanity, in order to create work worth sharing.”

While I haven’t yet read Hayes’s book, I look forward to doing so. Her interview got me really fired up, especially the part where she talks about the indispensability of art in sustaining movement work:

“If I didn’t, very intentionally, make space for art and for joy and for love in moments that aren’t about the horrors of this world, the parts of me that believe it doesn’t have to be that way might dry up and die. I have to nourish those parts of myself, I have to nourish my hope. And never underestimate the importance of art in doing that, by the way. Under all circumstances, under all conditions, we will always need art because it helps us remember the many versions of life that have been and could be. That we do not live in a cycle of inevitability, but in stories that can be rewritten.”

This is the part of the newsletter where I’m supposed to warn you against indulging too much. Where I acknowledge that self-care is all well and good, but that there actually is an appropriate amount of self-loathing or control or clock/pocket-watching—it’s just more moderate than what you’ve been told. But neither Charlotte nor Hayes do this. I think they both recognize that their audience’s problem has never been apathy; that traumatized, burned out, oppressed people cannot be chastised or threatened out of their immobilization. I’m not sure that anyone can. What they do offer is encouragement and clarity, premised not on our inherent need for punishment, but on a recognition of our humanity. You matter. We matter.

And if you matter, then so do your acts of creation, whether they happen on your body or elsewhere. I return, as I often do, to Maya Cade’s piece on the role of the artist in Black cinema, life, and Palestine from last year, “For All We Know and For All We Cannot Yet See.” Art can be a tool, if deployed with intention, she writes, “a testimony to the change of social order and an unbinding of the ties of colonial, capitalistic, and racist fantasies.” Of course, there is greater emotional risk in taking yourself, and your art, seriously than in succumbing to their dreams of annihilation. “If [your work is] not that important to you, how can it become important to anyone else?” wonders Charlotte. Valuing your art—and yourself—takes courage, a word that appears in Maya’s piece 10 times, one of them in this sentence: “[p]erhaps courage is the point awareness becomes movement and movement makes way for transformation.”

Your subscriptions help me pay the bills, allowing me to keep publishing work that’s mostly free for everyone, so thank you kindly for your support.

If you’d like to support me in other ways, you can like and share my posts, preorder my new book, Casanova 20: Or, Hot World, or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

Since 2023, the vast majority of Gaza Strip has been bombed and destroyed, displacing around 2 million people who need shelter. The Sameer Project is raising funds for tents, cash, and other vital supplies. Screenshot your donation of any amount and I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content. Please share the fundraiser in your networks!

Laying my cards on the table here: the concept of trans “social contagion” is the pathologization/criminalization of our family and community lives!

Not to mention the threatening construction of the thought experiment itself…

I’m reminded of Julian K. Jarboe’s viral proverb: “God blessed me by making me transsexual for the same reason he made wheat but not bread and fruit but not wine: because he wants humanity to share in the act of creation. I am only doing the Good Works here on Earth as intended!”