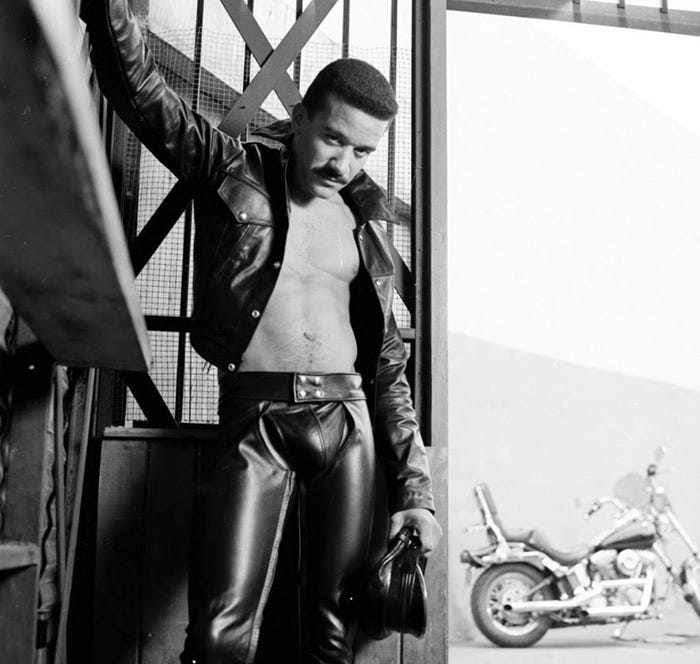

Iconic shot from “History of Black BDSM,” Dark Connections

In a recent BAD GAY column, the good doctor cautioned an advice-seeking pervert against confusing therapy with a good time.

Kink does not have to be self-care and kink is not therapy. Kink, done well, can feel therapeutic and cathartic and like self-care, but going into it with the idea that you are in some sort of grind to find your own limits sounds fairly stressful and not particularly joyful for anyone involved.

Not only is kink not therapy, but the desire to make it so can actually leech it of the pleasures offered us by a dangerous, sexy time among friends (or strangers!). When you try to make kink and therapy the same thing, in other words, you deprive yourself of the benefits of both. In this case, I agree with Bad Gay.

Where does this urge to make kink good for us come from, and why does it seem…if not common, then ambient, particularly at the moment? An example of this phenomenon might be a recent podcast interview with a popular online BDSM educator whose trauma-informed approach to so-called “sane and healing” BDSM boasts a variety of curative and therapeutic properties. While there are aspects to the educator’s approach that I wholeheartedly agree with—like her embrace of the power of kink to reimagine nonconsensual trauma in consensual circumstances, which I think is something a lot of players can relate to—there are others that I find deeply concerning, most of which popped up in the podcast episode but can be found echoed across her social media platforms.

It’s not just the educator’s casual conflation of BDSM with therapeutic interventions in comparing it to exposure therapy; relaying a story of likening BDSM to therapy during therapy with her therapist; and failing to correct the podcast host when they do the same that gave me pause. Taken on their own, I would probably have ignored them because I am aware that there are many approaches to BDSM that aren’t like mine. We know that players can be mystical, spiritual, occultist, crunchy, sensual, strictly sexual, strictly asexual, professional, romantic, nerdy, religious, clinical, medical, artistic, “primal,” and more, I’m sure. For me, I’ve been mindfulness-pilled enough to occasionally use the word “practice” to describe what I do, which I see as an amalgamate of connection with my gay and class history, somatic exploration, bodyhacking, and horny filth.

It’s the additional context that gives me pause, and makes me wonder whether this therapy kick isn’t something deeper. In the same podcast episode, the educator goes on to frame gay leathermen as scary or aggressive based off of pretty “mainstream” leather aesthetics (the color black and the bad UX of old cruising websites, basically) and because the community itself is not always easy for outsiders to access, not appearing to understand that this is by design. She also offers other heteronormative framings of BDSM that I won’t get into here, in the interest of time.

With this additional homophobic and heteronormative commentary, one begins to wonder if promoting the aspects of BDSM that are conducive to health, Wellness TM, and sanity* and vilifying the aspects that are scary, yucky, criminalized, challenging, dykey, and faggy don’t serve a greater purpose. In seeking to justify more easily sanitized aspects of BDSM by claiming that choice aspects of it are good for us, this educator engages with leather’s detractors on their terms, not ours. This is where the concept of respectability politics comes in handy. Instead of challenging anti-BDSM moral panickers and policymakers with, No, it is actually good for me to get stepped on by a woman pretending to be my Mommy, what if we were just honest?

I don’t care if it’s good for me. It doesn’t need to be good for me for me to be allowed to do it.

Leather may well be healing. It may well help address and resolve trauma. It may well aid us in becoming better, more well-rounded people. For me personally, this has been true in some respects. But it may not—and so what? The way you (consensually) have sex or explore sensation may be fucked up and nasty and dirty and pointless and hedonistic. It may hurt you, or never make you a better person, and this has been true for me, too. I have a scar that says Our first date <3 on my back (which I often forget about, it being on my back and all) carved by a person that I will no longer play with. The circumstances of the scar and the relationship were not particularly good for me, though the scene itself was one of the most fun I’ve ever had. Was this scene not good BDSM, or not BDSM at all, for those reasons? Should it have been prevented, my partner and I saved from ourselves, even though we both consented?

Good scenes and bad scenes, and even harm and abuse that happen within scenes, should have no bearing on whether it is acceptable to participate in leather and leather subcultures, especially when it comes to the interventions of the state via legislation and provision of resources and services, or lack thereof. Nonconsensual violence is unacceptable everywhere, but the state and its many tentacles have a funny way of only wanting to prevent it when doing so will harm, imprison, or destroy a community. We don’t need to justify BDSM with the idea that it can also somehow be good for us, like kale. Not only is this an insulting and counterproductive prospect, but it simply doesn’t work. Capitulation never does.

These conflicts are not new, even if the BDSM educator in question, who seems not to have a strong grasp of leather history overall, doesn’t realize it. In her intro to Guy Baldwin’s Ties That Bind, a collection of essays by the well-known leatherman and psychotherapist, cultural anthropologist and leatherdyke Gayle Rubin writes:

“…the gay movement had to move beyond simple affirmations of ‘gay is good’ to more nuanced understandings of the joys and sorrows and variety of gay and lesbian life. Similarly, the leather/SM/fetish movement needs the luxury of deeper and more complex discussions of the unique pleasures, and particular pitfalls, and endless diversity of what we call, for lack of a better term, ‘leather.’”

(I’m struck, re-reading this, at how we have come to describe leather as a “community” rather than a “movement.” Something to consider for all of us marginal people, I think.) Our rhetorical needs, as leatherpeople seeking to defend ourselves and our <gulp> communities, have evolved since the early days of American leather. They also vary, surely, depending on the other identities you bring with you to leather. Players of color, professional fetish workers, players with children, players across the gender and sexuality spectrum, players with disabilities and illnesses, players who are criminalized for a variety of reasons—it’s not unreasonable to suspect that the ways in which we talk about ourselves might not suit other sub-communities (or -movements, as it were). For example, how did the racial segregation of the U.S. military affect black leathermen of the Old Guard differently from the white leathermen? As a rhetorical device, “Leather is good, actually,” may have worked differently for these groups. This question might be easier to answer if not for, as noted in the Dark Connections page linked above, the scant evidence regarding the history of people of color within the early stages of the leather community.

Many of us have been told our whole lives that we are bad, and that just by being what we happen to be we are harming ourselves and others. How we choose to engage with this moralizing, and ultimately punitive, propaganda—for even choosing not to engage is in itself a form of engagement—matters, and doing so without legitimizing the arguments of your enemies—or worse, playing into them—is important, and also really fucking hard. This is why learning your history as a leatherperson is both so important and so damn hard to do. The current online censorship of sex workers, for example, is not only an assault on one of the most marginal of labor forces, which is disproportionately peopled with the most marginal among us, but also the art, history, and scholarship of kinky, queer, trans, incarcerated, POC, fat, disabled, and otherwise criminalized people that may now lost to those who come after us.

If they’re not destroyed altogether, the paraphernalia of subversive or radical aesthetic and sexual practices face commodification, which uses us to make money for them and which seeks to rehabilitate that which is inherently unrespectable. We see it happening all around us, the fucking and healing to be found in BDSM streamlined and repackaged as products to be bought and sold and accumulated by figureheads and companies that are airbrushed, managed, and branded in a similar way that cultural and spiritual practices associated with much older histories, cultures, and struggles are extracted from marginal—and especially, primarily, racialized and colonized people—and marketed right back to us.

If this rant sounds at all familiar, might I direct you to a similar tangent in my recent validity series:

Here was another account spoon-feeding leather to people who see it as a plug-in to their online brand rather than as a tradition, a lifestyle, a community-based politics, or just plain old dirty fucking, all while people practicing leather—most of them sex working, trans, and/or of color—are being even more censored on IG than ever before, despite the platform’s attempts to obfuscate its racist, ableist, fatphobic, and whorephobic policies with empty gestures to nuance in its ever-evolving TOS. Feeling valid might be of use to people with no skin in the game, but for others, the squishy benefits of validity simply don’t go far enough.

I promised to talk more about the therapeutic relationship, how commodification impacts it, and the perspectives of those who see BDSM one of only a few options for mental health care, self-care, and healing in a country where the medical industrial complex has a death grip on all of us. Still, there’s only 24 hours in a day. I’ve been a faithful reader of P.E. Moskowitz’s Mental Hellth, which will definitely be informing the next, and hopefully final, entry in this series, so take a look over there while you wait for more.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial. Read Part 1 and Part 2.

*I wrote about why we as a community have been trying to move away from sane/insane framings of BDSM last year for Lifehacker.