As a kid, I was a very good reader. Now that my attention span has been mutilated by social media and burnout, I’ve become a fairly bad one. Because I read multiple books at a time in small, short chunks (which I’m sure affects my retention in a negative way) and am often easily distracted, keeping up with my nightstand always feels a little harder than it should.

I started an annual book list back in 2018, which I’ve since discovered keeps me focused on reading for longer stretches, motivated to discover new writers and kinds of writing, and accountable to rooting out my own biases and blank spots1. If you’d like to read more and don’t find the idea of a book list anxiety-inducing, I recommend trying it.

I wish I had the time to write about everything I read. In lieu of that, you’ll find below a few thoughts on where my mind’s been lately.

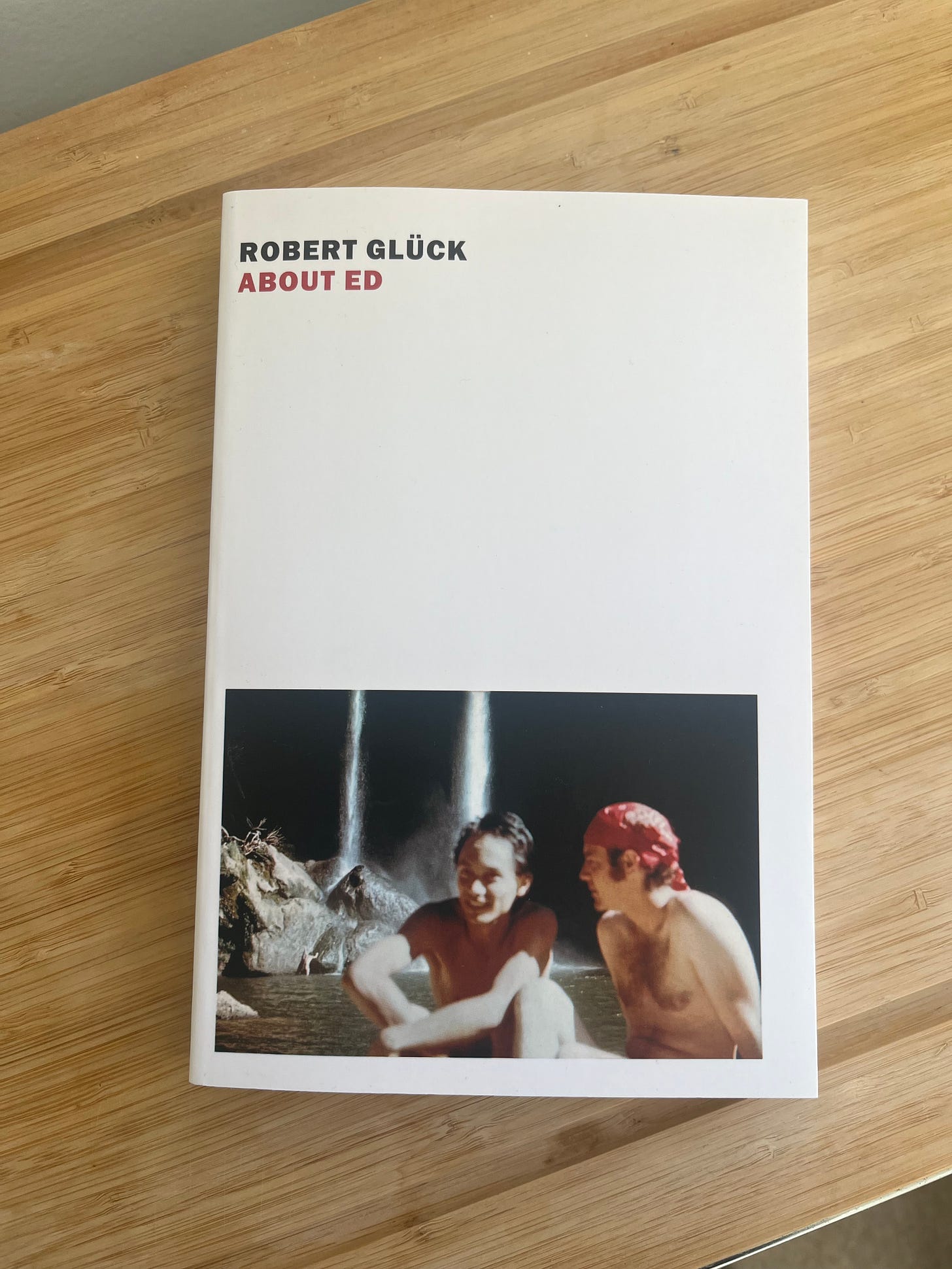

About Ed, by Robert Glück

In May, Bambi and I went to see Bob Glück and Shiv Kotecha at the Finnish Kaleva Hall in Berkeley. Bob read a scene from About Ed, wherein he joins his friend and former lover Ed for a meal that the latter’s terminal illness has almost rendered him unable to eat: Ed is dying and Bob must watch. Over dinner, Bob’s love and resentment waltz across the horrible, tedious beauty of his friend’s suffering. I feel sleepy and itchy as though an emotional demand will be made, and what will I do then? Bob wonders. I sense his death behind the door.

The selection almost brought me to tears. Afterward, I said hello to Bob, who I interviewed a few years ago for the NYRB reissue of Margery Kempe, and greedily secured the promise of an ARC when they were available.

Like I Wished, the 2021 autofiction novel by Bob’s contemporary, Dennis Cooper, About Ed is about orienting present grief through past and future grief. Homage, portrait, AIDS memoir, novel, and death ritual, it commemorates and perpetuates the life of the artist Ed Aulerich-Sugai, who died in 1994. Funny, sexy, bereaved, and galactically aphoristic, it moves mysteriously but seductively through time and space and perspective and “fact”—just as often “about” Bob, or someone else he knows, as the eponymous departed. As Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore wrote in her NYT review, Glück writes through digression, in conversation with the inevitable and the unknown at once.

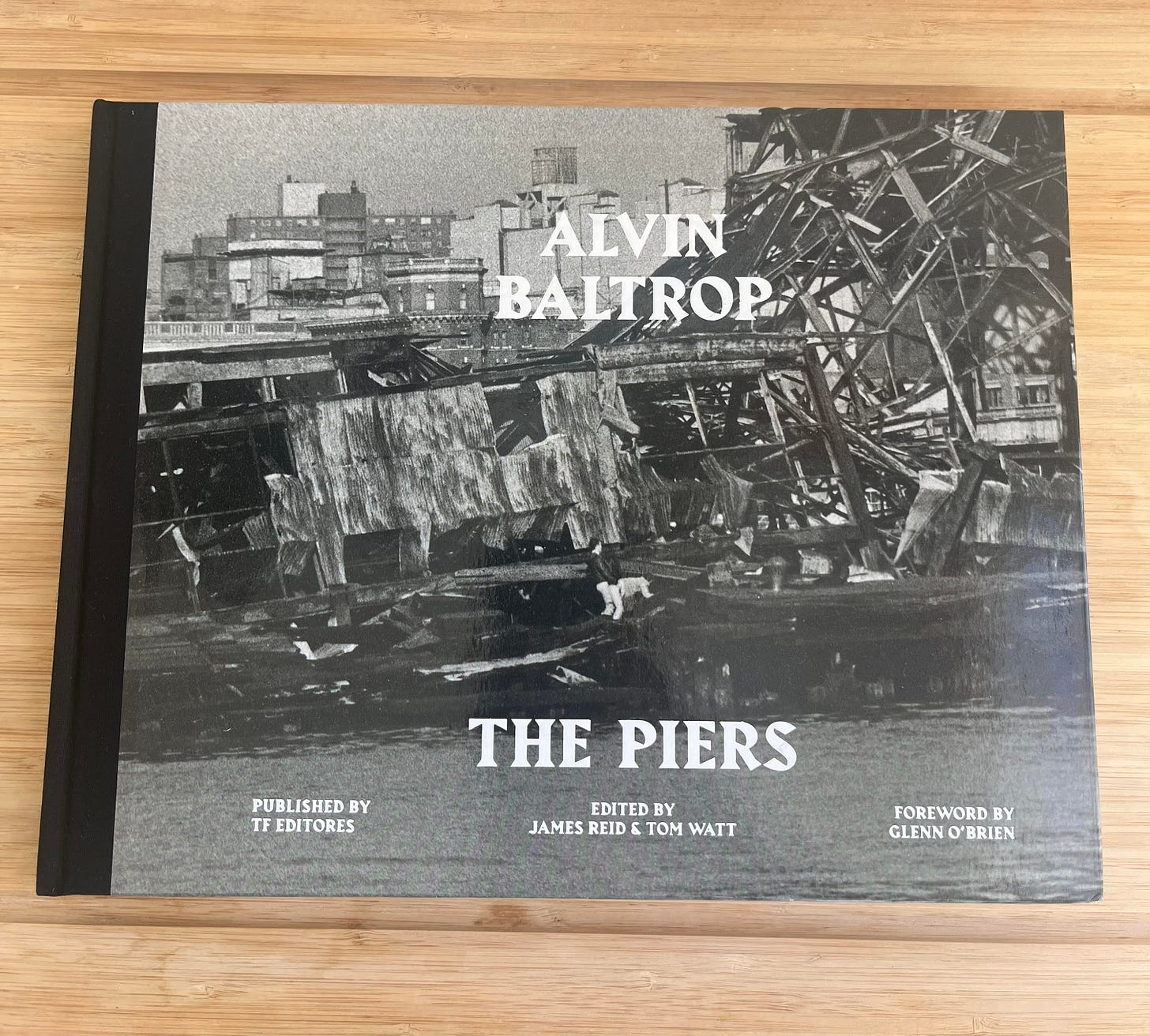

Alvin Baltrop: The Piers, ed. by James Reid and Tom Watt

An anniversary gift from Jade. While this Corvette of a coffee table book is stunningly curated, I was disappointed in its lack of written information about Baltrop himself. Both introduction and foreword have little to say about the photographer’s life or craft, focusing instead on the Hudson River Piers on the West Side of Manhattan where he went to meet and photograph other men from 1975 through 1986. Those old cruising grounds have now been gentrified into oblivion by businesses, condos, and institutions like the Whitney Museum of American Art, which in 2018 held a beautiful retrospective of the white artist David Wojnarowicz, who is quoted in the introduction of The Piers, while the book’s black subject is hardly to be found.

This lack could be an editorial choice; Baltrop, who often lived in precarity and didn’t become famous until after his death in 2004, is far less archived and written about than Wojnarowicz—maybe he didn’t leave any good quotes behind2. It could also be a creative one, as suggested by Glenn O’Brien’s foreword, which prefers to contextualize American post-war cruising culture (no “sissies” there, he insists!) over examining Baltrop’s role within it, as a way of maintaining the anonymity the photographer shared with his subjects.

Considering what we know of Baltrop’s history as an unsung black gay artist, if this was a choice, I don’t think it was the appropriate one, and the book suffers for it.

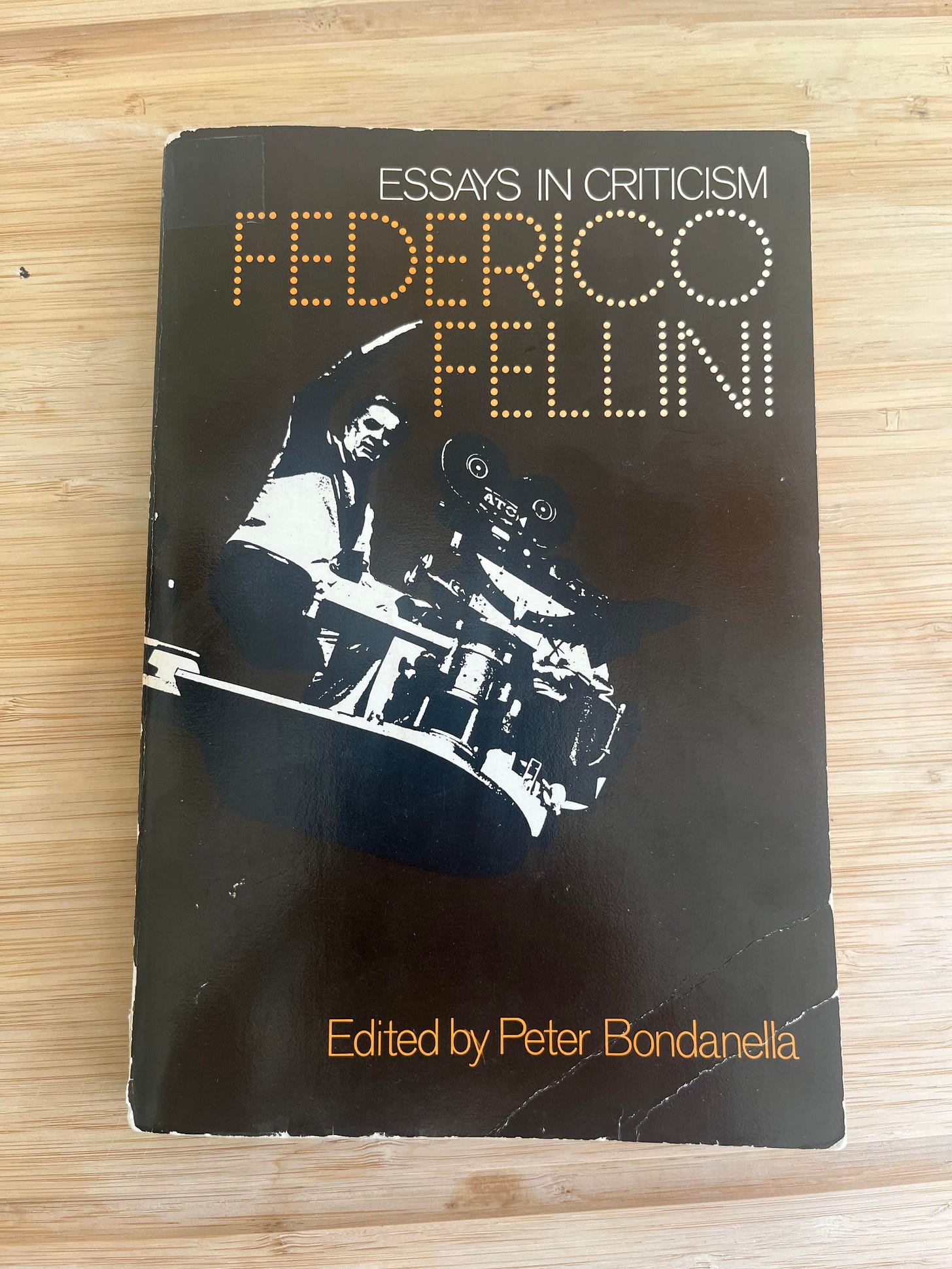

Essays in Criticism: Federico Fellini, ed. by Peter Bondanella

I’m writing something about Fellini right now (and have before with this piece on La Strada [1954]), so stay tuned for that.

Until then, I won’t say much except that the great director’s interviews are delightfully melodramatic and deeply thoughtful. Fellini calling himself a storyteller, liar, and gossip rather than a filmmaker? 10/10. Fellini saying, I have a sort of paralysing feeling for everything concerning me, and therefore for my films? King shit.

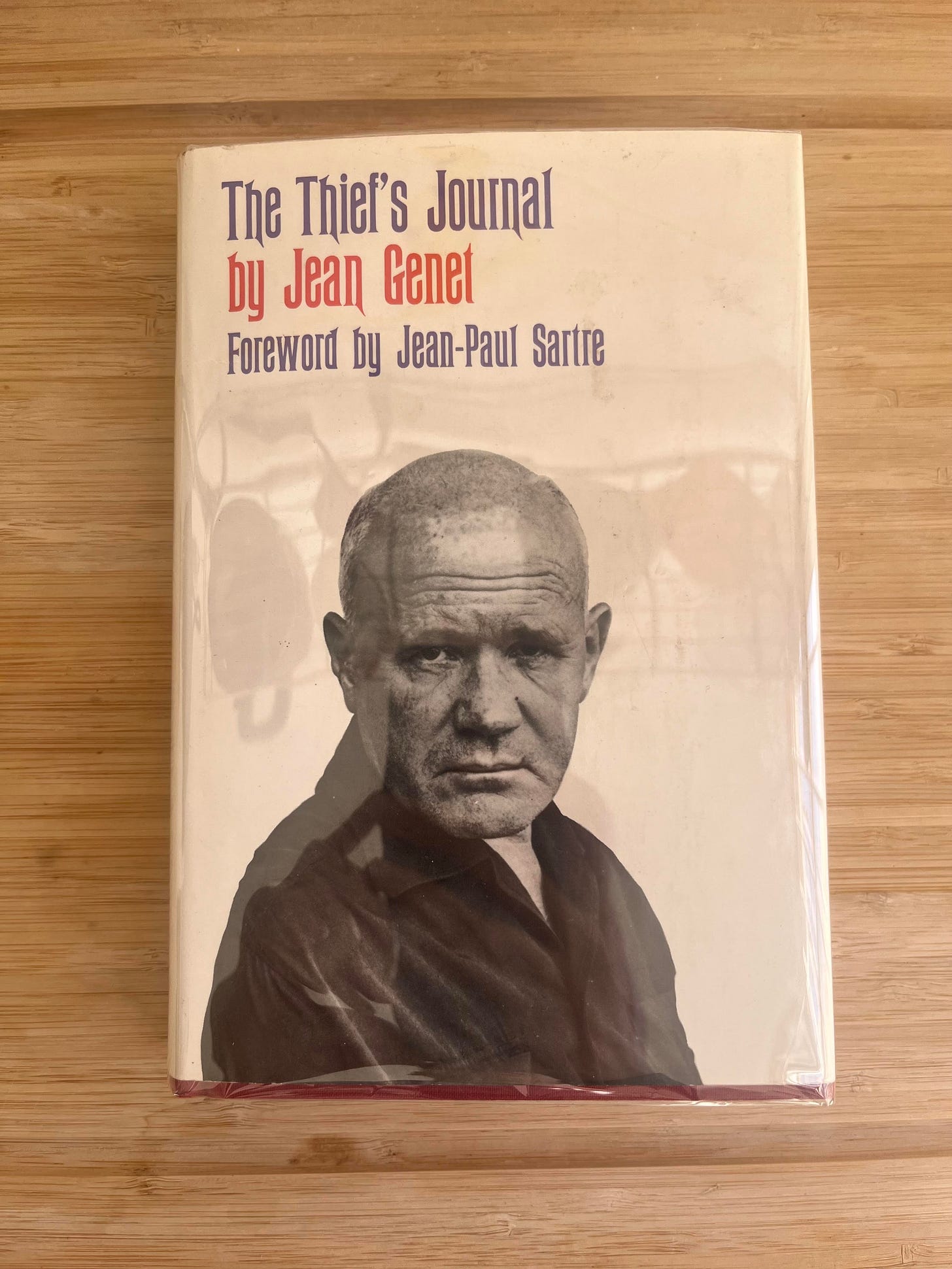

The Thief’s Journal, by Jean Genet

I was halfway through this book when I wrote about it a few months ago, basing the piece on the marginalia I left in my ratty used paperback. Unaware that I already had a copy, Jade gave me this lovely hardcover (also for our anniversary), which feels like a sign to finally finish the job.

Narrow Rooms, by James Purdy

Daemonumx’s description of Narrow Rooms included the words “gay crucifixion,” so I just had to borrow her copy3. My familiarity with Purdy’s short stories didn’t prepare me for the passion, violence, and perversity of Rooms’s doomed love triangle. I hope to include this novel in my eventual expansion on the necessity of the “sex scene” in a future newsletter.

A Girl’s Story, by Annie Ernaux

Ernaux was not on my radar before her recent Nobel, but I hadn’t felt particularly compelled to seek her out until Frankie cornered me at Bruise to insist that she’s actually doing what Kundera thinks he’s doing.

With A Girl’s Story, Ernaux revisits a character she once wanted to forget completely: herself at 18 years old. Alternating between the first person and the third, often without warning, she fluidly yokes her current identity to a girl who no longer exists (except that she does, and she’s writing this book). With the present tense lending to the strong sense that this is an active, dynamic investigation of the past, Story is a transposition of the state of image and sensation to that of words, as Ernaux writes. The tenderness with which the author handles her younger self only seems possible because of the time dividing them, bravely though does she excavate the shame surrounding the social ostracism she suffered for a man who didn’t care if she lived or died, who didn’t even care enough to properly reject her.

A Girl’s Story is a girl’s story, as it is a grown—at this point, elderly—woman’s story, but because it transcends the trauma trends of recent literature, it is also a writer’s story. Why remember? Why empathize with oneself, or one’s enemies, or one’s mother, who didn’t understand, or one’s first lover, a man who hasn’t once thought of you, though he’s a central figure in a book that you’ve written over 50 years later? Why write at all? This is what Ernaux says:

But what is the point of writing if not to unearth things, or even just one thing that cannot be reduced to any kind of psychological or sociological explanation and is not the result of a preconceived idea or demonstration but a narrative: something that emerges from the creases when a story is unfolded, and can help us understand—endure—events that occur and the things that we do?

Nights in Aruba, Dancer from the Dance, and The Beauty of Men, by Andrew Holleran

Other than “dream blunt rotation,” I can’t say much about these freshly arrived bragging ARCs because this newsletter needs to get out the door!

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

The recent reading’s been looking pretty white, which reminded me to get moving on a friend’s rave recommendation of Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double-Consciousness.

Here’s one from a Guardian piece about him: “Although initially terrified of the piers, I began to take these photos as a voyeur [and] soon grew determined to preserve the frightening, mad, unbelievable, violent and beautiful things that were going on at that time.”

Daemonumx discovered Narrow Rooms thanks to Adam Baran’s Anthology Film Archives program of the same title.