Last week, I received a call from a man looking for my uncle, who apparently owes him money. It wasn’t out of any sense of loyalty that I blocked him—I haven’t seen my uncle in ten years, since he was running a scared-straight/conversion therapy racket on his property out in the Sierras. Out of curiosity, I tracked down the Instagram account for the now-bankrupt business he started with the money of the man I blocked; in dipping his toe into a new industry, it seemed, my uncle was soon lost at sea.

I examined the photos of him and his family, who, in true Davis fashion, were also his employees. Other than looking older, little about them had changed in the past decade. From my uncle’s frizzy, Viking-style beard, to his wife’s baggy, joyless dresses—femininity-as-chore for the woman he referred to as “Mother”—to his children, the drab young adults who I suppose are my cousins, these biological relatives of mine are the worst kind of white people: Disneyfied versions of the more aesthetically striking skinhead who harbor more or less the same politics.

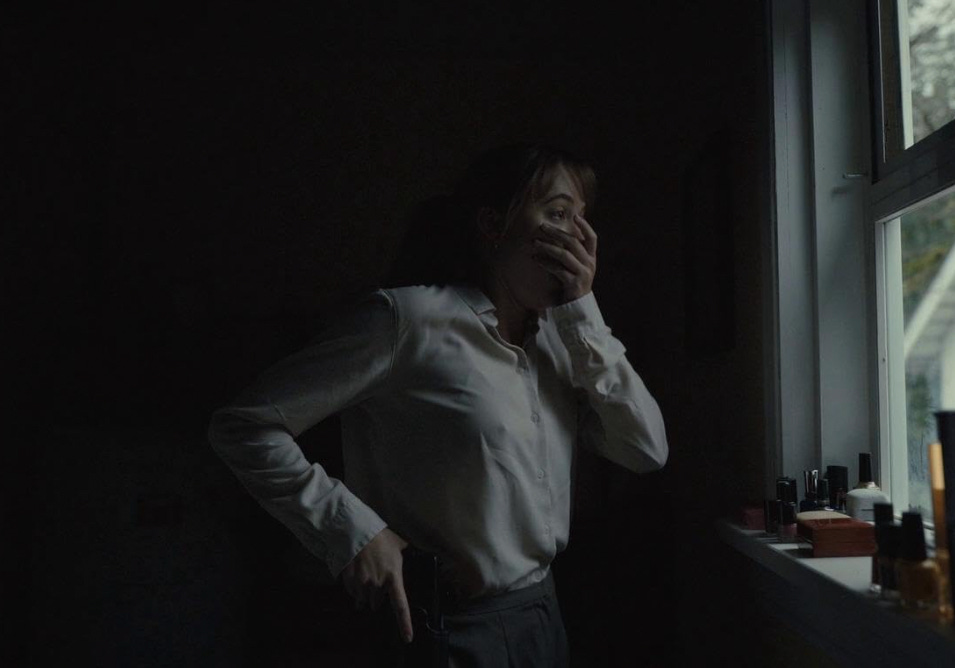

I felt nothing for them. But blocking my uncle’s creditor still felt vindictive, rather than merely practical, and I was out of sorts for the rest of the day. Though it smarts to be deadnamed (as will happen to me forever thanks to the digitization of legal and medical records), my resentment had been stirred by this reminder of my natal family and my lack of feeling for them. These reminders of nothing, which aren’t unfamiliar to me, always have the paradoxical effect of making me feel something in the most unpleasant way.

Also last week: bored and over-caffeinated, I did an anonymous AMA on my own Instagram. Among the submitted questions—What are my romantic relationships like? What do I think about this or that director? How have I integrated COVID safety into my sex life?—was this one: Why don’t we have a good written ethics of sadism?

I’ve condensed the question for you here, meaning you can’t see how its considerably longer original phrasing telegraphed, to my ears, a proud ignorance of leather and a disdain for the sadistic experience, something about which, as a masochist, I feel called upon to defend; I’m also suspicious of people who came to leather through a college critical theory course rather than, you know, gay sex, as they tend to arrive with a lot of bourgie hangups about a subculture that is definitionally criminalized1 and otherwise marginal2. Despite my irritation, however, I replied with lots of recommended reading—because how could I blame this person? These days, leather seems more accessible than it really is because its signifiers have been commodified by marketing and pop culture, and its body, if not its underbelly, exposed, via social media, to people (gay and otherwise) who have no actual stake in the lifestyle. Why don’t we have a good written ethics of sadism? Not that we need one, my dear, but how dare you assume that we don’t?

In my response, I included Guy Baldwin’s Ties That Bind: The SM/Leather/Fetish Erotic Style: Issues, Commentaries and Advice [sic]3, a collection of his Drummer advice columns from 1986 to 1993; it’s not theory, which I think is what my interlocutor wanted, but I thought a psychotherapist leatherman’s perspective had something to offer, ethically speaking. At around the time he was writing that column, Baldwin also wrote a series of essays on leather’s Old Guard, having discovered that the younger leatherfolk around him insisted on conceiving of these mystical creatures as this “rigid and dead thing rather than an evolving, living cultural entity.”

“Stranger still,” he writes in “The Old Guard: Classical Leather Culture Revisited,” “is the fact that the Old Guard is usually talked about by people who weren’t part of it as though it were some kind of monolithic, behemoth…homogeneous and static, neither of which was the case…”

Ignorance is no sin, especially when it comes to leather, a subculture that has been repressed and co-opted since the beginning. To revel in one’s own ignorance while disparaging that about which one knows nothing, however, is to display an arrogance antithetical to our tradition, which that Instagram person would have known if they had read beyond the sexy university press releases of the past year or two. Mama, let’s research the American homosexual military veterans who split off from The Wild One-style motorcycle gangs of the 50s to create their own hierarchical rough-fuck culture!

To be sure, the leathersexuals that came before us aren’t unproblematic. Baldwin uses language like “feudal nobility,” “godfather,” and “baron” to help us conceptualize the way that leather families were organized among the white, cis, masculinist players of the 50s, 60s, and 70s. One was not socialized into leather as a vast, interconnected, highly political counterculture—movement, even—but into the norms, mores, and protocols unique to their region, city, and family. These “clans” or “tribes” subverted the nuclear family while also reproducing its organizational logics of white supremacy and patriarchy (power relations that define leather today, by the way). Nevertheless, they served an important purpose for leathersexual men, supplying, as Baldwin writes: “advice for love life and sex life; a home-life with our own kind; information about how leathersex worked; a place to barbecue on weekends; information on who were the responsible players in the community and who was best avoided; the very important Protocols, of course; and general mentoring.”

Unlike Baldwin’s Old Guard, my leather family is multi-gender, multi-racial4, and only incidentally ex-military (no one I know fucks with vets who haven’t been radicalized by their enlistment, denounced American imperialism, etc.). But both serve as replacements for our straight families of origin, who not only didn’t want us, but were incapable of supporting our safety and happiness as leathersexuals. The nuclear family is for reproducing capitalism; the leather family is for fucking.

In stark contrast to the way leather’s insularity has been on the decline since Stonewall (Baldwin has a lot to say about why this is), I suspect that our families have never been more important to that safety and happiness. But the Old Guard wasn’t just designed to protect its members: it also guarded “the mysteries of leather ritual” from outsiders, those who would have “exploited them for theatrical effect, chic, or merely from dilettantism .” Though the Old Guard has faded away, based on what we see of “S/M” in ad campaigns, TV shows and books, and social media, some things never change.

In 2024, the “mysteries of leather ritual” are not hidden from view in Brooklyn’s leatherqueer scene. At Bruise, the public monthly party put on by Daemonumx and Jade, there is no cover or dress code, although horny leatherwear is highly encouraged. While most of us who come are perverts, no one is turned away. I think this is a good thing, and compatible with the time and place in which we find ourselves: “we recruit,” as the Lesbian Avengers used to say.

A few weeks ago, Bruise hosted a pop-up strip club to fundraise for DecrimNY (fundraising is an old biker and leather tradition, as Baldwin writes). As sex workers, strippers are naturally adjacent to leather, and the dancers at the fundraiser were intentionally in leather, meaning they are parents, siblings, and children of other leathersexuals. As I watched them being sexy for their community, I felt like a sister, an aunt, a mother, even: Isn’t she beautiful. What a good job they’re doing. Look at him go! Watching their friends and lovers use infantilizing terms of endearment like baby, hold cameras like proud papas, praise them and cheer them on as they leapt, spun, bounced, hustled, and threw ass, I felt old, or maybe just young, because these are the feelings I still associate with my straight family, and the life it was supposed to give me.

That these feelings—reflexive and nostalgic, natural and unnatural—can transcend my old life feels good. But I can’t feel them without thinking about my old life, which feels painful. Despite everything I have gained by that loss, I still grieve it, even though, if you could see my uncle’s work Instagram, you would wonder what there could possibly be to grieve. I think I always will.

Support DecrimNY.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

In the first version of this post, I wrote that leather was “definitionally poor.” While the economic marginalization of queer people, including gay men, is undeniable, I think that it is inaccurate to claim that all leather was inextricable from poverty, especially as we go further back into American leather history, and especially regarding gay men. I got hung up on leatherdyke history and made too broad of a claim. My mistake!

I went to college! I have bourgie hangups! And I came to leather because it was the only way to survive a bad situation, which means I accord it a respect that weekend-warrior trust fundies just don’t, maybe can’t.

Not to be confused with Ties That Bind: Familial Homophobia and Its Consequences, by the great Sarah Schulman.

I don’t remember Baldwin writing about race in his book, and glancing through his other writing—including a book on “slavecraft” (with an intro by Patrick Califia!!!)—there is nothing addressing race, racism, or white supremacy. Without making any claims about Baldwin’s personal beliefs, or going so far as to assume that he has never written about these topics, I am going to hypothesize that his milieu was pretty white.

❤️❤️❤️