On finding a reason to write

an interlude

In his newest for Harper’s, William T. Vollmann goes to Reno, Nevada, to bribe three outdoor men for their stories. For some petty cash and a beer or two, Roland, Happily, and Jesse submit themselves to Vollmann’s queasy inquiries and grudging pity, which all parties know will result in no material improvement of their circumstances (unless you count the opportunity to guilt-trip an extra blanket out of their interlocutor in time for the night’s snowstorm). Himself an indoor man, Vollmann uses their suffering to reverse engineer an essay about sheltered people’s implication in the brutal institution of American homelessness.

Vollmann is sympathetic to the plight of his subjects, but he doesn’t dissemble his reasons for seeking them out. Am I my brother’s keeper? he wonders. I preferred to say that I wasn’t; it kept my expenses down. But I could be pleasant enough without committing myself to rescuing anyone. He has taken the Amtrak’s California Zephyr from Sacramento to Reno in order to gather the tragedies of impoverished persons because he needs money to avoid becoming one himself, having lost his will to work—to write—since losing his daughter the year before. My accountant warned that if I did no better in 2023 (or did I have until 2024? You see, since Lisa’s death I kept having memory troubles; you would be impressed by all the times I mislaid my raincoat, keys, train tickets, passport, and mind), the Internal Revenue Service would no longer tolerate my clever little write-offs.

Over the course of almost 9,000 words, Vollmann’s “Four Men” gradually reveals its true focus: not our country’s most vulnerable, who per our author have been grimed, smoked, frozen, and sunburned by, who knows, perhaps Fate herself, but the lies that maintain the fiction of indoorness. (Didion had it that we tell ourselves stories in order to live; perhaps we also tell ourselves stories in order to not die). The gritty, squinting Reno summoned by Vollmann—the streets’ muddy slush and casinos’ fluorescent smoke, the Truckee River’s snowmelt bloat (almost picturesque, he concedes, holding fast to a wry remove that even Twain could envy)—condenses into a slick but hard-packed sludge, as glacially slow and profoundly dissociated as the man sketching it for us.

Vollmann’s daughter died horribly and unnecessarily, and also because of a few chance circumstances that, had the author been a little luckier in a system that makes us all unlucky, could have been circumvented. But he wasn’t, and they weren’t. “Four Men” is a display case for his grief, which is, to Frankenstein my metaphors, trapped under the only clean ice this side of the Sierras: we can see it, we can feel its horror, and yet the worst is still to come, as the human toll of the American dream—people like Roland, Happily, and Jesse—is insulted by the squeamish calculus of indoor people everywhere (He had gotten a beer and the promise of twenty dollars out of me. How much could a blanket be?…) Vollmann, like me, or any other reader who can be assured that they’ll have a roof over their head, for another night at least, can choose to ignore or rationalize the fact that these men sleep in the snow. What he can’t do is not know it.

I don’t get writer’s block. Not to brag, but it’s my superpower; I have a lot of opinions. As I’ve tweeted before, Jade does a scathing impression of me on this topic, complete with hair-twirling: “i just had a thought. here’s 10k words. it’s about sex.”

But sometimes I do get depressed, which on top of being unpleasant is the only condition in which I don’t care to write as much as I normally do. I’m not blocked; I’m bereft. Because like, why? For what? There’s rounds in the chamber, but the revolver’s gathering dust. If writing is about meaning—and I often suspect that I don’t understand anything unless I’ve written through it first—and there’s none to be found, then why waste the energy?1 Chekhov’s limp dick over here.

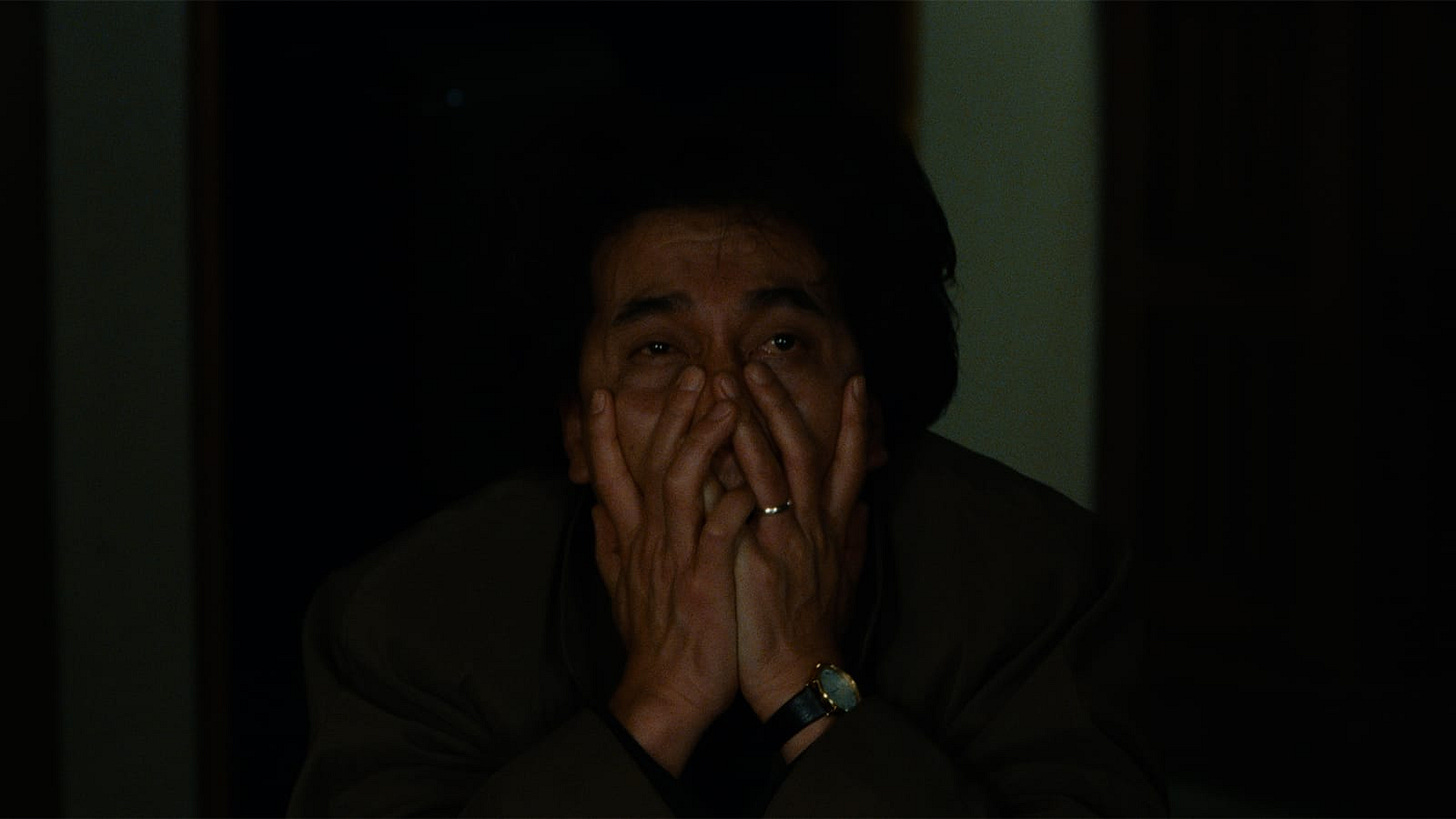

Aspects of my current depression can certainly be distinguished from geopolitics—relationships, a health thing (it’s always a health thing with me!)—but I can’t deny its connection to the international assault on the people of Palestine2. To be clear, the feelings this stirs in me are neither compassion fatigue nor burnout. They are sadness, grief, and horror, undergirded by a nauseating lack of surprise. Fundraising, feeding, filing out into the streets with the many, many likeminded people who also refuse genocide is good for us because it is, we hope and pray, good for our friends on the inside. But everyone lucky enough to be at a physical remove from the bombs and white phosphorous has an algorithm to be haunted by, the place where terror is at once suppressed and managed, revealed and marketed. For me, those haints are, at the moment: a young woman cradling her child’s death shroud; desperate men, many of them not even old enough to be called men, frantically digging through rubble with their bare hands; a young American activist’s last living photo, her broken mouth her ultimate portrait.

Reasons to write come to me naturally. They cluster like toadstools, they crowd like curious children; I take them for granted in the most proud and selfish way. So what do I do when they don’t come? When being alive is not enough on its own, I have learned to live so as to have something to write about. I reverse engineer being alive. If reasons to write can’t be found, then they must be made, sometimes from necessity, if that ouroboros can be forced to make a lick of sense.

This one is not as tidy as I’d hoped. I seem, like Vollmann, to have lost my way along a straight line, distracted by things that feel more real than art. This being the case, I leave you with a few grafs from “Four Men,” about a man and his dying daughter, and the three men he came to know because of her, or lack of her, and how none of it mattered in the slightest. Where is the meaning? Where is the meaning?

On the day before my return I called, and again she did not answer. So I told her that I would see her in a day, and that I loved her. Wasn’t that enough? But as drunks will, she mixed up the dates and thought that I was at my studio. On the previous night the paramedics had taken her to the emergency room just as they found her, that is without shoes. They intubated her and let her sleep it off, because as a policeman had long since told me, she was a known drunk. In the morning, when she was hydrated and somewhat sober, she refused counseling for alcoholism, so out she went, in her stocking feet. Why not write her off, alongside Roland, as homeless by choice? It was only two or three miles to my studio, but it happened to be raining. She waited for me in the parking lot for hours. (I torture myself over and over with this.) Then a kind homeless man gave her water and led her to the women’s shelter, where a crazy lady threatened her all night and tried to attack her.

Had I been where she imagined or hoped I was, I would have rushed to hide the alcohol, as usual, then fed her, wrapped her in blankets on my sofa (being also bulimic she was thin and got cold easily), and stayed beside her, postponing for another day my brilliant monetizations of the miseries of others. (Oh, I was plenty compassionate, all right; I had written books to prove it.)

So I had found my three men and paid them; hadn’t I been good? What else could I have done? I had failed Lisa, so why not fail them as other indoor people did?

I am an evil person. I tried this on to see if I believed it. If that was so, then what about the indoor man at the coffee shop who had long since run out of pity for the homeless? Maybe I was better, because I paid for their stories and tried to raise other indoor people’s so-called awareness; or maybe I was worse, because I knew that the system was against them, yet did not help them more than I did. I considered this matter some more. Then, at least for five minutes, I stopped caring.

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

Although, in that case, why preserve it?

I have found writing by Charlotte Shane, context by Zoé Samudzi, tweets by Max Fox (whose writing I also greatly admire), and ongoing reading by outlets like Jewish Currents and N + 1 to be indispensable.

This knocked me for six, you've really articulated something here.