David Lee Roth

On arrested development and precocious adults

In preparation for this installment of DAVID, I’ve been listening to a lot of David Lee Roth. Between that and my regimen of EMDR music (as insisted upon by my therapist), this nightmare has had a strange soundtrack.

Not that the soundtrack has been unpleasant. I have a soft spot for what’s now known as classic rock—I mean, I’m from the Sacramento River Valley, where FM radio stations will devote entire an hour, every day, to Led Zeppelin—and Van Halen is one of the first bands I can remember recognizing. My mulleted Uncle Erik, no older than 19 or 20, would rip down the driveway to my grandma’s farm in his white jeep blasting “Jump,” then leap out from behind the whee into the gravel, twisting his fingers into air guitar.

I thought he was the coolest motherfucker alive. Now he’s a fundamentalist dentist who refuses to expose his sons to people like me; the oldest made it all the way to puberty without knowing that menstruation was a thing that happens to people. Life’s a trip.

Anyway, Gnarcal roots notwithstanding, I successfully resisted the urge to deep-dive into Diamond Dave’s life, which I’m going to justify by pointing out that the man, the myth, the legend is really more of an experience than something to be quantified or known.

Like, who cares that he was born in Bloomington, Indiana? Or that he’s (of course) a libra? That he’s seemingly the only person in the world who refers to bandmate Eddie Van Halen as “Edward,” or that after leaving Van Halen he was an EMT for a while, freaking out unsuspecting citizens of New York City (“Sir, please remain calm while I reach down between your legs and…ease the seat back”)?

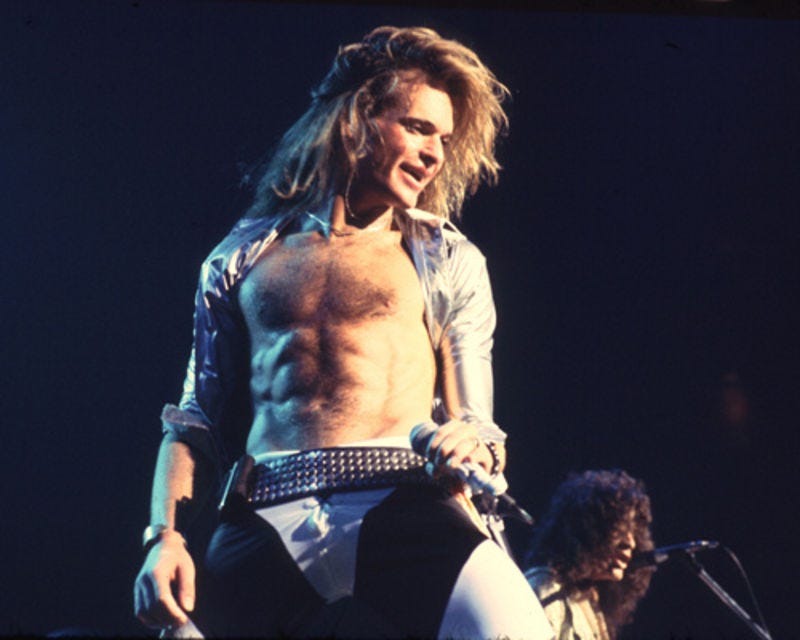

The Diamond Dave Experience isn’t about data—it’s about listening to him splinter the sound-barrier, his howl like Mariah’s bird whistles rawed on testosterone, or being mesmerized by his crotch aerials, his hip humps, his coke-fueled ascents of Yosemite’s Half Dome in feathered hair and rainbow spandex.

Still, if you let a few of his interviews from over the years sort of wash over you, things begin to reveal themselves.

It’s not uncommon for celebrity interview subjects to be asked about their childhoods, but I noticed that DLR talks about his A LOT, often returning to it in his conversations with journalists and reporters, always in the auctioneer-fast bricolage of unrecognizable idioms, inside jokes of which only he is the only member, and malapropisms for which he’s often lampooned. Consume enough of these interviews, and you’ll be able to recite from memory the story of the hyper, Ritalin-medicated little boy whose dinnertime antics were referred to by his parents as “monkey hour” (interestingly, little else is said of his immediate family). DLR attributes his fame to his childhood dreams of one day being in “show business” (always “show business,” not “music” or “rock n’ roll”), comparing it to running away to join the circus and the adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Not that many of his explanations, stories, yarns, or bizarre metaphors make complete sense. Listening to DLR talk about, say, what makes for good rock n’ roll sounds is a lot like jazz: You get the general idea, but you probably wouldn’t be able to reproduce it yourself.

It’s not that he comes off as a stupid or thoughtless person, exactly—his reference points are many and diverse, and he has a true talent for extemporaneity—or even someone who’s coked out, although he’s obviously that, too. Rather, DLR seems too distracted to fit his ideas together, taking for granted that you’re following his often disjointed message. You get the idea while there’s a lot going on in there, it’s utterly disorganized, like a tornado that’s picked up an entire Walmart.

Then again, if still waters run deep, as they say, then what do white waters do? Very few people are lucky enough to have the gift of gab, but being composed or articulate doesn’t necessarily say anything about substance. I’ve compared DLR with Jerri Blank before, and while there’s an uncanny physical resemblance, the real similarity is in the way they talk—the rapidfire patter, the wall-eyed schmoozing, the way they can both snap into a script, especially when nervous or cornered, that can’t conceal the skein of panic below the rote.

Compare this tendency with his performances, and you start to wonder if DLR isn’t more mania than charisma. Don’t let the hair, the clothes, the mugging, the ribbon- and sword-dancing fool you—while his life couldn’t be more different than Jerri Blank’s, it’s possible to draw connections between her arrested development (“Hello. I'm Jerri Blank, and I'm a forty-six year-old high school freshman”) and his.

Which is why I’d offer 1984’s Hot for Teacher as a microcosm of that arrested development. The video features the elementary school-aged version of each of Van Halen’s members. Shadowed by their grownup selves, the kids lust after a sexy teacher—who is lusting after them back while performing a striptease in the classroom—reveling in the fantasy of mutual sexual desire. I don’t need to get into the role of this trope in our culture, especially for boy children (remember Mary Kay Letourneau?), and how fucked up it is.

I’m not interested in arguing about different times, or whether or not it was all in fun, or whether I’m overlooking the playful cluelessness of adult men indulging in what was, 35+ years ago, a less shocking fantasy. It doesn’t need to be said, and anyway, I’m more interested in affect.

The more I watch him, the more I feel the discomfort of seeing a precocious adult in action. Jerri Blank is a dark and twisted version of that; a lighter, more palatable one might be Martin Sheen as President Jed Bartlett in The West Wing; though I adore him, Sheen gives me a strong whiff of Shirley Temple both in character and out, the energy of a person who enjoys, above all, the visceral pleasure of being a good little boy on stage where everyone can see.

Which is a crucial different to bear in mind with DLR. Some little boys and girls get attention the need by being bad, but not all of them. Even though Van Halen, a rock band with codpieces and corny double entendre, is more closely associated with badness than goodness, DLR is often careful to make clear in interviews that he’s not all that bad. He’s sexy, not erotic, he says; outlandish but still, he insists, classy.

It casts the hypersexuality of Diamond Dave in a different light altogether. I think a lot about performative sexuality in service of fame and power. There are many massive stars and famous people who build a reputation on their sexuality that is, of course, disingenuous. Madonna comes to mind. Or Donald Trump. People invested in your perceiving of them as sexual, but for whom the attention is obviously the main turn-on.

DLR’s carefree veneer, in my eyes, anyway, gives way to anxiety. It’s not the anxiety of the rock frontmen who didn’t give a fuck, middle-fingering their way through fame and drugs and women, the Axl Roses and Ozzy Osbornes and flameouts chronicled in The Decline of Western Civilization Part 2: The Metal Years.

His is the anxiety of someone who wants attention for being good.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial.

gnarcal 🤙🏼