What I've been reading, watching, and looking at

on Torrey Peters, "A Woman Under the Influence," and more

I love these quarterly check-ins. This time, I’m including a few movies and a painting, but I’ll only be talking about one book (kind of). Though I had a fun summer with Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming Pool Library, Gary Indiana’s Rent Boy, and Joan Nestle and John Preston’s Sister and Brother: Lesbians and Gay Men Write About Their Lives Together, plus a few others, there are only so many hours in the day—especially when you’re wrapping up the MS for your third novel.

What I’ve been reading

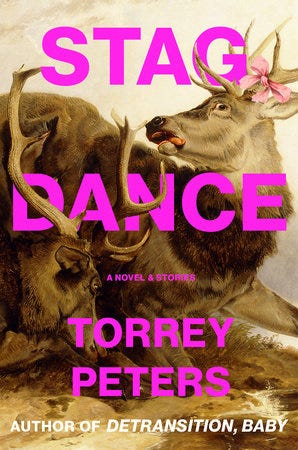

Stag Dance: A Novel & Stories, by Torrey Peters

In 2019, a few months after I moved to the city, Torrey Peters invited me to lunch. I had read Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones, but that was all I knew about her, if fiction can tell you anything at all about its author. She arrived at the restaurant on a hot-pink motorcycle, briskly unhelmeting the golden hair that doubled as her lit-girl aureole (Detransition, Baby was just around the corner), before greeting me with her disarmingly soft voice. She was polite in the self-effacing but deadly serious manner of Midwesterners, instantly putting me at ease, or what passed for it at that time in my life. Over our meal, we talked about writing.

We still do. Reading my ARC of Torrey’s newest book, Stag Dance—comprised of Infect Your Friends, two other novellas, The Masker (2016) and The Chaser (2020), and the eponymous novel, a tall tale-style yarn about gender trouble at a turn-of-the-century logging camp—I had the funny, pleasureful, obvious-in-retrospect realization that our friendship lives within our books, each a long and painful gestation of chapters nurtured, abandoned, executed, revivified, fretted over, and then finally whisked away into the world. (I’m mixing my metaphors here, but considering our oeuvres I think a little biological illegibility is in order.) Over the past five years, we’ve talked about everything under the sun, but there’s never a conversation with Torrey that doesn’t somehow find its way back to our work.

While Stag Dance the novel is new material, Stag Dance the collection has the shape and feel of a retrospective, which is highly appropriate for a brilliant though still-maturing artist who has managed to survive the (well-deserved) hype and circumstance of her debut, which included her nomination for the 2021 Women’s Prize for Fiction, as well as its transmisogynist outcry from an unwashed minority whose open letter against it could have used a copy edit. As Torrey writes in her acknowledgements, Stag Dance brings together a decade of work that has “[puzzled] out, through genre, the inconvenient aspects of my never-ending transition—otherwise known as ongoing trans life,” with stunning and satisfying consonance.

In my brief review of each novel/la, I’ll keep it as impersonal as I can under the circumstances. But I will say, unprofessionally, that I see in Stag Dance’s successes the qualities that I adore in Torrey as a person: her delicacy; her sense of humor (highly sophisticated, with gleeful glimmers of adolescent raunch); and her uncanny ease with metaphor, as if even the most complex idea were merely an apple for her to lower into your reach by applying just the right amount pressure to its branch.

Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones: I had forgotten how cinematic this one is. In a post-pandemic future where everyone is trans—or rather, where everyone is forced to scrap for the sex hormones that keep our hair and muscle and fat in the preferred states and locations—our narrator toggles between her apocalyptic present foraging for estrogen and her no-so-distant t4t past with Lexi, the messy doll who started it all. Now that we’ve actually had our viral plague here in the real world (though it hasn’t fucked with our endocrine systems in a way that’s quite so interesting), aughts/teens spec-fic (mine included) has acquired a certain naiveté. For all its technical irrelevance, however, Infect Your Friends retains the narcotic charisma of transsexual littermate lovers, a page-turning momentum, and the breathless final grafs that made it pop in the first place.

The Chaser: We return to the scene of the crime—adolescence—not from the perspective of the gender-funny kid, but their grudging admirer. At a Midwestern Quaker boarding school, a butch jock gets involved with his roommate, femmy proto-girl Robbie, only to discover that detaching with his masculinity intact is harder than he would have guessed. There’s so much to love about this story, which I think remains my favorite of Torrey’s work, but what I love the most is that Robbie has the social status and emotional intelligence to be its villain, rather than its victim—the chaser’s chaser. But this reading begets another: that Robbie is not the villain at all, but simply insisting on not being disappeared by his erstwhile friend, which, in a world in which men are gendered through the de-gendering of other people, can only be understood as violence.

Stag Dance: Because Stag Dance is boldly written in dialect and because I have heard Torrey recite from it at “Trans Disruptions: The Future of Change,” reading this novel gives me the hilarious sensation of seeing my willowy friend in drag as bewhiskered Babe Bunyan, the self-loathing, ox-sized yeoman who yearns to wear the fabric triangle that will mark him as “the skooch” to be courted at his logging camp’s stag dance. Poised against his rough-hewn ribaldry is Torrey’s strongest setting and descriptive work yet, as well as her always-original approach to gender as a thing we desire more than inhabit. As Babe, triangle firmly in place, muses, “Maybe the order of events is jumbled, but it seems that the declaration and the aspiring happen in the same moment.” Ok, backwoods Judy Butler!

The Masker: Not all transsexuals have a red-pill moment, but for many of us an excruciating decision must be made: do I go full-time? Force-fem and sissy interiority (do you know the difference between a woman’s garment and a sissy’s?) is Torrey’s bread and butter, and so long as there is a social cost to transition, particularly for women, her essential treatment of these topics will continue to fascinate.

What I’ve been watching

All That Jazz (1979): I love art about people who are terrified of sex, and few are more so than Bob Fosse’s semi-autobiographical stand-in, theater director, choreographer, and compulsive philanderer Joe Gideon (played by the gorgeous Roy Scheider, as I always call him). As a musical theater hater, I was nonetheless thrilled by Jazz’s beautiful choreography, fabulous casting, and mesmerizing assembly; its writer clearly has an intimate understanding of rhythm. Still, I spent most of the screening wishing I were watching 8½ instead.

A Woman Under the Influence (1974): Watched it again because of Gena Rowlands’ passing. For a loud movie, Woman has many moments of profound quiet. Though its scenes of naked tragedy, including the one where Rowlands’ Mabel begs her husband, Nick (a heartbreaking Peter Falk) not to institutionalize her, may draw the most attention, for me the most memorable is when Mabel waits on her tiptoes in the street for her children’s school bus, almost dancing with happy anticipation. It made me miss my own mother in a way that was almost not unpleasant.

Greta (2018): This one should have been drowned in a bucket. A crazy piano teacher living in New York City stalks, tortures, and kills young girls, and yet we’re bored. Chloë Grace Moretz stuns—in the bad way—and even the great Isabelle Huppert is wooden and unsatisfying, though she chews up one or two scenes, like when she forces her victim to serve her in the restaurant where she works.

The Spook Who Sat by the Door (1973): Both brilliantly understated and depressingly on the nose, Ivan Dixon’s radical adaptation of Sam Greenlee’s novel follows the first Black CIA agent (a slow-burning Lawrence Cook) as he builds a guerrilla army intent on overthrowing the government. The FBI had it pulled from theaters, and I can’t imagine it would fare very differently as a new release today.

What I’ve been looking at

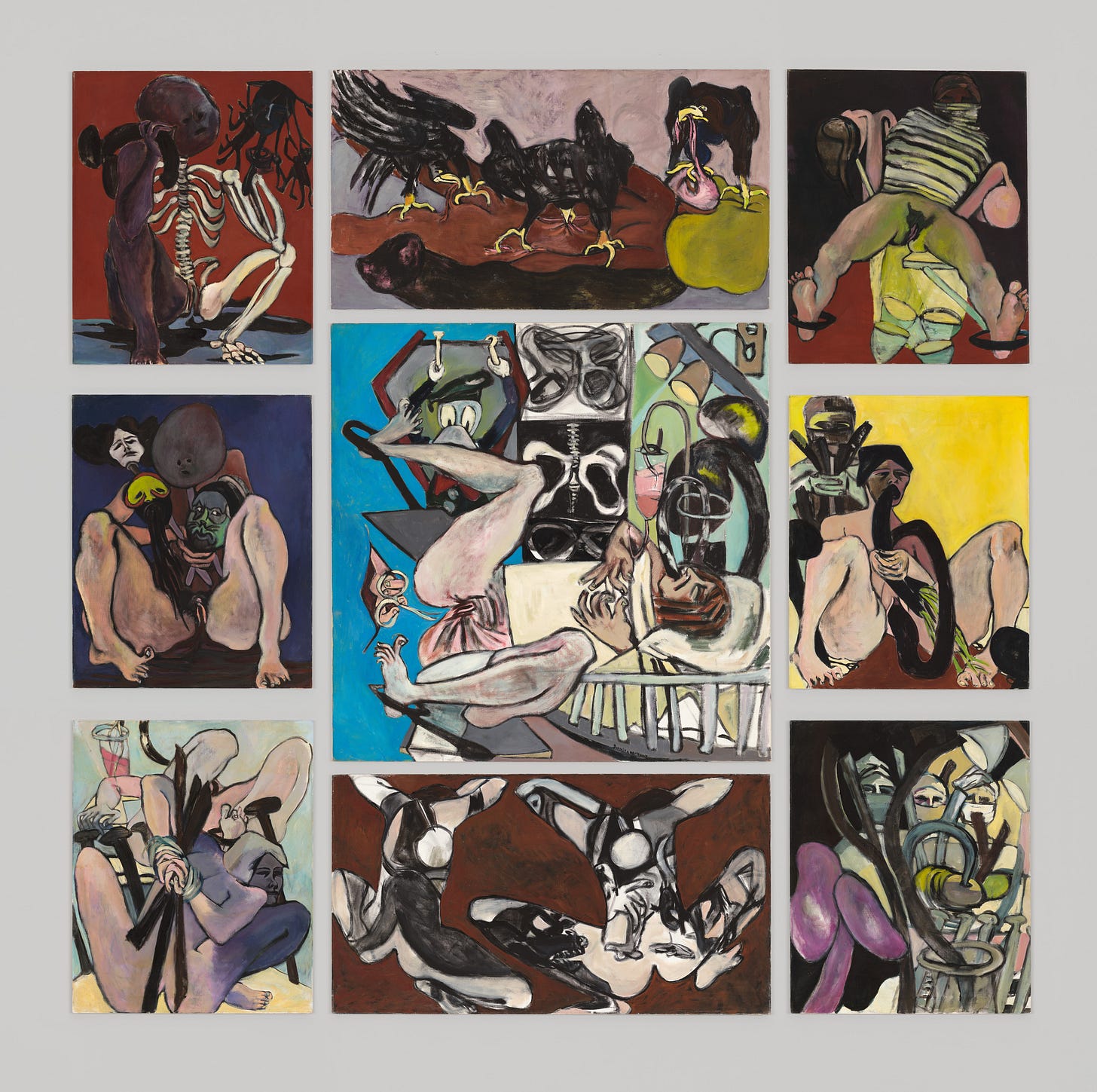

“Is It Real? Yes, It Is!” by Juanita McNeely: Going through my notes, I came across a photo I took of the Whitney placard for this painting, a depiction of the artist’s experiences with illegal abortion because legitimate doctors would not do it in order to save her life from cancer—to protect the baby, you see. Even while acknowledging the brutal circumstances of her procedure, the placard describes the “cruelty and carelessness” of her male doctors as “perceived.” Every time I read the word, I become livid. I have not had an abortion, but I have been butchered; this painting, with its necrotic bones, suffocating bandages, leering Donald Duck, and faceless MDs stopped me dead in my tracks.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of fundraiser for Palestinians trying to survive within Gaza or relocate to safety. Gaza Funds is one place to get started.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

Gena was the greatest. Check out my post on her please.