Two romcoms

to distract you

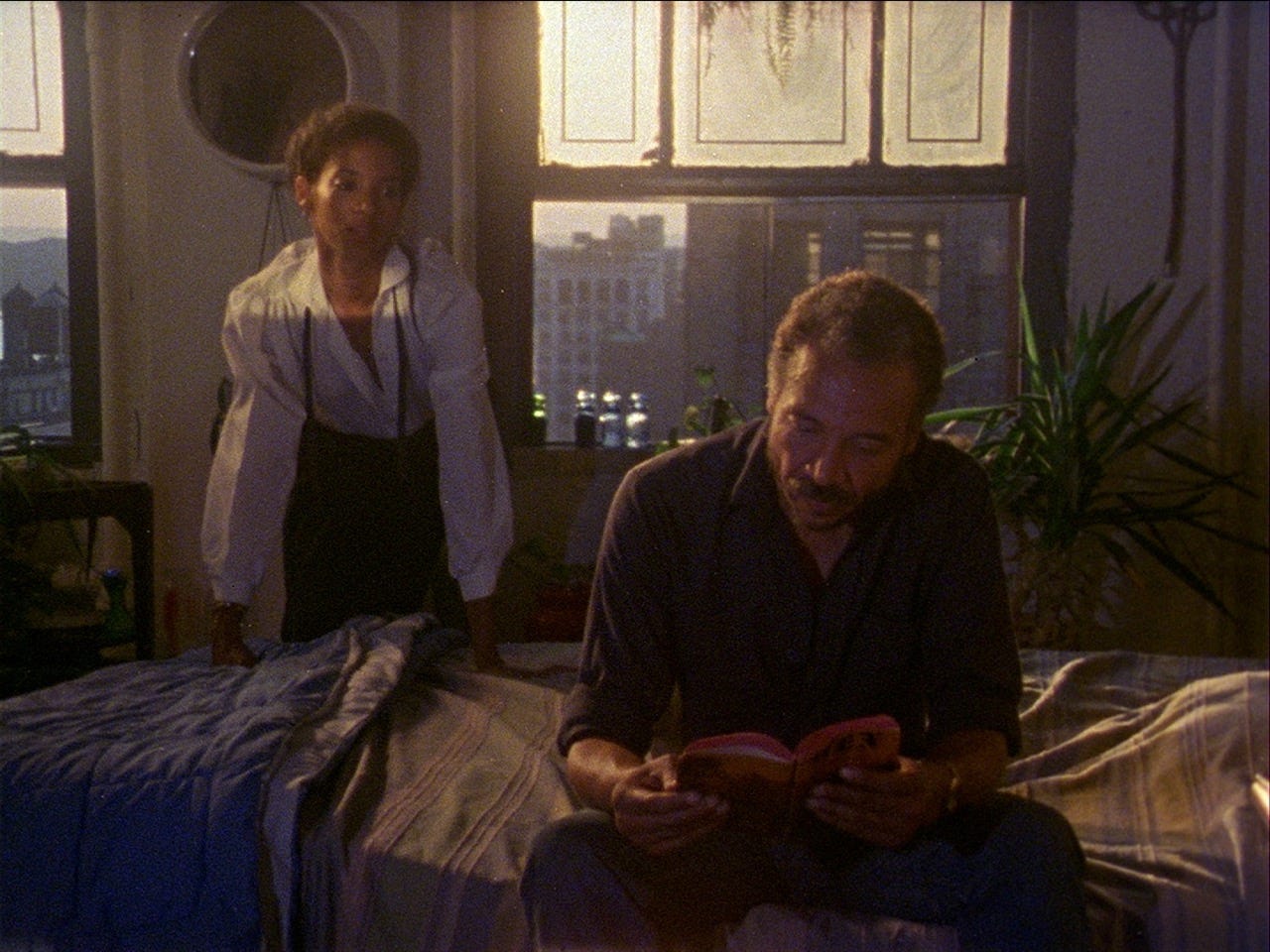

Losing Ground (1982)

Kathleen Collins’ semiautobiographical drama is a gorgeous indulgence: art about art made by artists in love. Sara (Seret Scott), a philosophy professor whose marmish glasses belie latent passions, is annoyed when her husband, Victor (Bill Gunn), a painter with the aesthete’s entitled appreciation for beautiful women, disrupts her study of “ecstatic experiences” when he whisks them to a Nyack rental for the summer.

To say that Losing Ground is a love triangle (or quadrangle, as it becomes when horror icon Duane Jones, whose interest in Sara is her rebuttal to Victor’s wandering eye, turns up) goes a way toward describing the plot, but still fails to capture the vibe. Losing Ground’s melancholy never devolves into tragedy; its dreaminess never loses focus. Collins’ cool, confident direction is thrillingly original, especially its fourth wall-breaking machinations in the student film that Sara joins as her own attempt at the Art that her husband holds in such overweening esteem.

What I love about Losing Ground is that there is never the feeling that something is lurking around the corner; that our heroine will be lost to bitterness; that Victor’s maddening charisma (I dare you not to fall for Gunn) will win out over Scott’s almost affected earnestness (perhaps it would be better to call it a stylized authenticity). The overall emotional effect is that of a romcom—in that I felt safe—that is also, somehow, painterly!

I’ll be thinking about this one for a long time.

Secretary (2002)

When I was a freshman in college, I was accidentally accepted into a writing workshop for upperclassmen. “Oh,” said the professor, glancing up from the attendance sheet. “You’re not supposed to be here.” I was afraid of him—he was always stoned, or seemed to be, and never said anything that made sense—but he didn’t kick me out.

I can’t remember if I had applied to the workshop out of cockiness or ignorance. This was around the time I experienced my first psychotic episode, so I can’t remember much else, either, other than that I felt a deep disappointment in the quality of everyone’s work, including my own. I do, however, remember this: after class one day, the professor handed me a copy of Mary Gaitskill’s short story collection, Bad Behavior. “I think you might like it,” he predicted.

He was right. The collection famously includes “Secretary,” the story upon which Steven Shainberg’s much bubblier Secretary, which I saw not long after, is based. Lee (a vulnerably plucky Maggie Gyllenhaal), who has just graduated from in-patient for a self-harm problem, is struggling to adjust to life outside when she gets a job as a legal secretary for the strange and demanding E. Edward Grey (a perfectly monotonous James Spader). As they begin to recognize a shared affinity for a more adversarial kind of romance, Secretary skips adeptly through all the necessary cliches: old flames, cold feet, girl power. I don’t think it’s a spoiler to report that, like any good romcom, its ending is a happy one.

Along with a lot of solid characterization, set design, and acting, Secretary embraces the silliness of D/s as part and parcel of, rather than distinct from, the whole romantic enterprise. What results is an original yet true take on the genre, one that—despite the aught’s-era tweeness, goofy soundtrack, and compensatory heterosexism (cringe, even for a romcom)—more or less holds up, which I knew for sure when Lee and Grey’s first negotiation moved me to tears, as it did when I watched it in my early twenties.

But time, of course, has enriched this scene for me. When I was younger, I thought my emotion had been stirred by Grey’s promise to Lee that he could disappear her masochistic compulsions if only she would be obedient to him (a proposition to which she agrees with delight). Now I understand that it’s not absolution that Lee has found in Grey, but connection. As she later says of him, “I feel more than I’ve ever felt, and I’ve found someone to feel with.”

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

love Losing Ground, and Kathleen Collins’ work generally